Last updated: April 7, 2023

Article

Dayton Landscapes in Aviation History

"For some years I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man. My disease has increased in severity and I feel that it will soon cost me an increased amount of money if not my life. I have been trying to arrange my affairs in such a way that I can devote my entire time for a few months to experiment in this field."

- Wilbur Wright to Octave Chanute, May 13, 1900

During the late 19th century, several individuals attempted to invent a heavier-than-air powered flying machine. Otto Lilienthal, a German engineer, was the first to create a manned glider capable of sustained flight in the mid-1890’s.[1] Around the same time, astronomer Samuel Langley created a steam-powered plane, called an aerodrome. Although the War Department, likely motivated by the start of the Spanish-American War, commissioned Langley to further develop his aerodrome in 1898, his efforts proved unsuccessful.[2] However, these inventors’ contributions provided valuable technical aviation information, which engineer Octave Chanute collected and published in his book Progress in Flying Machines in 1894.[3] The Wright Brothers used this book along with other aeronautics publications provided by the Smithsonian in 1899 for their early glider designs.

On October 5, 1905, Wilbur Wright flew the world’s first practical airplane, the Wright Flyer III, for an unprecedented 39 minutes and 23 seconds at Huffman Flying Field in Ohio. This accomplishment represented the inception of modern aviation.

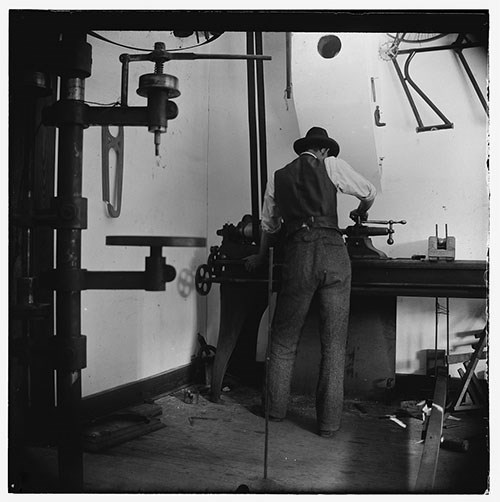

Wilbur and/or Orville Wright. Part of: Glass negatives from the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress

Wilbur and/or Orville Wright. Part of: Glass negatives from the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress

The Wright Brothers spent their youth in Indiana and Ohio. Orville and Wilbur’s parents, Milton and Susan Wright, moved their family of seven permanently from Indiana to Dayton in 1884. The Wrights’ parents supported strong family bonds, piety, and intellectual pursuits.[4] In 1889, Orville Wright, then a teenager, started a newspaper business, the West Side News at 1210 West Third Street. Wilbur later joined his brother in publishing the weekly local newspaper. In 1892, the Wright Brothers started another business, the Wright Cycle Exchange, where they repaired and sold bicycles eventually including their own designs.

The Wright Cycle Exchange originally operated out of 1005 West Third Street, then moved to 1034 West Third Street, 22 South Williams Street, and finally 1127 West Third Street in 1897. In 1895, at the 22 South Williams Street location, the Wright Brothers hand-crafted a small numbers of their bicycle designs. The popularity of their Van Cleve and St.Clair bicycles reflected high public demand for “safety” bicycles, which consisted of two wheels of the same size. The Wright Brothers’ bicycle business not only provided funds for their aviation experiments, but also likely helped them acquire mechanical knowledge useful for airplane design.

Experimentation and Invention

Like their predecessors in aviation, the Wright Brothers sought to design a controllable machine capable of operating in unstable conditions – similar to how the bicycle works. They used the scientific method to first identify the main issues preventing sustained flight and made observations about aeronautics using kites. The Wright Brothers alternated between the conceptual and practical application of their ideas to work towards a better understanding flight dynamics. Early on, Wilbur Wright made an important discovery about roll: by twisting or warping a wing to achieve a greater angle the more lift occurred on that side. The Wright Brothers wanted to test their roll-and-pitch control system on an unpowered full-sized glider, which required a hilly landscape with consistent wind. They decided on Kitty Hawk, North Carolina and traveled there in 1900.

These trials revealed critical issues related to the glider’s control and lift, so the Wright Brothers returned to Dayton and continued to revise their design at their bicycle shop at 1127 West Third Street. They also constructed a wind tunnel to verify the accuracy of lift and drag equations.

The Wright Brothers’ familiarly with bicycle mechanics contributed to their propeller design, which relied on a chain-and-sprocket system to transfer power to the propellers from the engine. In 1903, they took their powered airplane, the Flyer, back to Kitty Hawk and managed a sustained flight for 59 seconds and over a distance of 852 feet. Shortly after this flight, a gust of wind destroyed the Flyer and it never flew again. However, because of the accomplishment made that day by the powered aircraft, some consider North Carolina “first in flight.”

Wilbur and/or Orville Wright. Part of: Glass negatives from the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress

The field, while relatively flat with a meadow character, contained small hills or “hummocks.” Corn fields and a tree line surrounded the field while a large locust tree defined the center. These experiments required a space not only large enough to practice flying, but also highly accessible for repeated trials.

In the late 19th century, electric interurban lines increased in prevalence and expanded the Dayton market by connecting the city to rural areas. A nearby railway line at Simms Station made travel efficient via electric passenger car from the Wright's home and businesses in West Dayton to Huffman Field. In the spring of 1904, the Wright Brothers first transported materials on the electric interurban line and constructed a simple hangar in which to develop the Wright Flyer II and launching device. The Wright Brothers overcame the lack of consistently strong wind by dropping a weight from a tower at one end a monorail track, which pulled their plane fast enough for take-off.

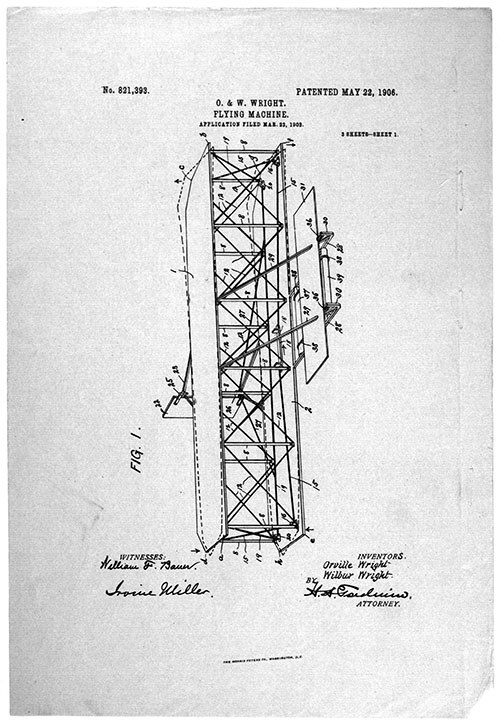

Part of the Wilbur Wright and Orville Wright papers, 1809-1979, Library of Congress

Through their continued trials at Huffman Field, the Wright Brothers progressed towards a more practical and durable airplane. The Wright Flyer III included features to control all three principal axis of rotation: a front elevator, rear rudder, and wing-warping system, as well as twin propellers and long skids for landing. This design was capable of advanced maneuverability and multiple take-offs and landings. After their revolutionary 39 minute flight on October 5, 1905, the Wright Brothers flew only once more in 1905 in part due to poor weather. They then focused their efforts on securing rights to their intellectual property by applying for a patent. The U.S. Patent Office granted one in 1906 for their 1902 glider design. In the following years, the Wright Brothers aggressively pursued what they believed to be patent infringement. This likely suppressed the growth of the U.S. aviation industry compared to other countries.

Wright Company Operations

Both a French syndicate and the United States Army negotiated deals with the Wright Brothers in 1908. The Wright Brothers also formed the Wright Company, which coordinated the Wright Exhibition Team and Flying School at Huffman Field. The Wright Exhibition Team operated only briefly from 1910-1911, while the Flying School lasted through 1916. The Flying School trained both civilians and military personnel. Famous aviators who trained at the school included Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold, Roy Brown, and Marjorie and Edward Stinson.

The Wright Company Flying School, constrained by the topography and size of Huffman Field, required students to follow a set course with only a few areas for take-offs. However, the field’s proximity to the interurban line, by then known as the Ohio Electric Railway, again helped mitigate its disadvantages. During the time of the Flying School’s operations, the interurban ran every thirty minutes from downtown Dayton to Simms Station. At the beginning of the 20th century, Dayton was one of the largest interurban centers in the U.S. This made travel convenient for flying students and spectators.

Wilbur and/or Wilbur Wright. Part of: Glass negatives from the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress

Despite the spacious new building and private investment from prominent capitalists including Cornelius Vanderbilt III, production quantities remained relatively small.The principles associated with mass production and Fordism had not yet been applied to the aviation industry. Instead, the Wright Company required versatile and skilled workers for motor fabrication, assembly, and woodworking. In particular, experienced lathe operators were needed to meet the degree of precision required for the wooden frame construction.

Wilbur and/or Orville Wright. Part of: Glass negatives from the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress

This innovative community supported entrepreneurs, as evident in the Wright Brothers’ printing, bicycle, and airplane businesses. Before the Wright Company confirmed the location of their new factory, the Dayton Chamber of Commerce urged the community to pursue the company to stay and helped them locate a site for the factory. From 1910 to 1916, less than 150 airplanes were produced at the Wright Company Factory. In 1917, Darling Motor Company purchased the property, but it retained it only for a year prior to bankruptcy. The newly formed Dayton-Wright Airplane Company bought it back in 1918 and manufactured specialized airplane parts in response to the army’s need for WWI airplanes.

Contemporary Landscape Use and Interpretation

The U.S. government recognized the advantage of developing its aviation capabilities as World War I tensions escalated. Not soon after the Wright Company discontinued use of Huffman Field in 1916, the U.S. government scouted the area surrounding the field and designated Wilbur Wright Field to train pilots. They also created another site, McCook Field, for engineering and research facilities. Eventually the government properties expanded and combined to form Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in 1948. In the 1940s, the Air Force used the airspace above Huffman Field to calibrate the speed of new planes.

NPS

West Third Street Historic District also displays historic character both as a suburban streetcar commercial block and through extant buildings associated with the Wright Brothers. These include the Hoover Block that contained Orville Wright’s printing business and the fourth location of their Wright Cycle Company shop at 22 South Williams Street. Today, the Wright Brothers’ printing business at 16 South Williams Street in Hoover Block serves as the Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center. The Wright Cycle Company building, a National Historic Landmark since 1990, was restored to emulate its original appearance and contains interpretive objects related to the Wrights’ businesses and early research into flight.

Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress

Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park Cultural Landscapes

Octave Chanute, W. De Fonvielle, and James Means. Progress in Flying Machines. New York: The American engineer and railroad journal, 1894.

The Wilbur and Orville Wright Timeline, 1846 to 1948, Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of Congress

National Register of Historic Places, West Third Street Historic District, Dayton, Ohio. January 25, 1989.

Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park website

More about NPS Cultural Landscapes

Aviation and the National Park Service

Notes

[1] NASA. “History of Flight.” Accessed 2019. https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/UEET/StudentSite/historyofflight.html[2] Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “Langley Aerodrome A.” Accessed 2019. https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/langley-aerodrome

[3] Octave Chanute, W. De Fonvielle, and James Means. Progress in Flying Machines. New York: The American engineer and railroad journal, 1894. https://www.loc.gov/item/31015366/

[4] Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “The Wright Brothers: The Invention of the Aerial Age.” https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/wright-brothers/online/who/1859/index.cfm

[5] Roach, Edward J. The Wright Company: from Invention to Industry. Ohio University Press, 2014.

[6] Wright, Nathalie. “Historic Context.” Accessed 2019. https://www.ohiohistory.org/OHC/media/OHC-Media/Documents/rp-23.pdf