Unlike the British prisoners held under Thomas Melville in western Massachusetts, the American experience at Dartmoor was generally remembered as miserable, unhealthy, seemingly endless, and—for many—deadly.

“And we further resolve, that every impression that we formerly entertained in favor of the British nation, as magnanimous, pious, liberal, honorable or brave, is utterly extinguished by the regular and systematic oppression…" —Statement made by a group of former prisoners, mostly Federalists from York, Maine, dated August 31, 1815

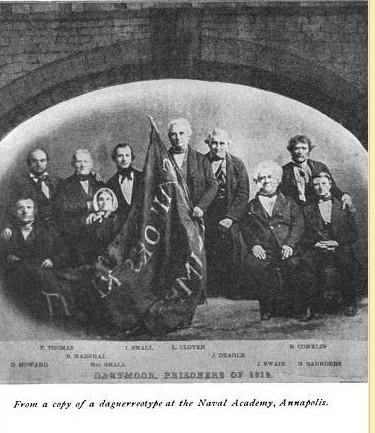

The first American prisoners of war arrived at England’s Dartmoor Prison in 1813. More arrived in the summer of 1814, transferred from the prison ships the British used to hold prisoners. As the American prisoners arrived, they joined more than 8,000 French soldiers taken prison during the Napoleonic Wars. Eventually, the prison housed some 6,500 U.S. prisoners.

The prison itself became the site of a notorious incident during the war. After American diplomats came to believe that a British agent in America was providing information to British commanders in Canada, they returned him to England. In response, the English prevented America’s agent for Dartmoor—the man responsible for helping ensure the American prisoners’ conditions—from visiting the prison. Not entirely aware of the diplomatic quarrels, the suffering prisoners held America’s prisoner-agent responsible for their poor living conditions.

The war ended with no clear plan in either government for organizing the release and return of American prisoners to the United States. Without a plan for their return, Americans remained interred at Dartmoor for a number of months after the war ended and the Treaty of Ghent was approved. The ongoing failure to get American prisoners home created the circumstances for the Dartmoor Massacre in April 1815.

The problem began when the prison commandant imposed a restriction on food rations. Later, as a number of American prisoners gathered outside the limits of their courtyard, inexperienced British guards began firing. By the time the smoke cleared, seven prisoners were dead and another 31 lay wounded.

Later, some American prisoners would see the event as an example of British “butchery, barbarity, and inveteracy.” One prisoner came away believing the British soldiers “murderous,” acting with “cool and deliberate malice.”

Ultimately, though, Britain’s Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs offered regrets and compensation to the victims’ families. The incident nevertheless created a sense of American bitterness toward the British for their treatment of prisoners, one that persisted for years after the war.

Last updated: May 24, 2016