Article

Daily Life at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

at the Central Branch, Dayton, Ohio

Courtesy of the Dayton VA Archives

Military Structure

The veterans living at the National Home branches were subject to the Articles of War, which dictated how soldiers should conduct themselves in war. This approach gave the men at the National Home branches a structured environment so they knew what to expect on a daily basis.

The residents were organized into companies of 150 men, commanded by a captain. Every morning, one captain designated as “Officer of the Day” inspected the buildings and grounds to ensure that all regulations were observed. A branch governor, normally a Civil War veteran as well, managed each National Home branch. A deputy governor, secretary, and treasurer supported the branch manager. Later the National Home branches added additional managerial positions including a quartermaster, surgeon, and chaplain.

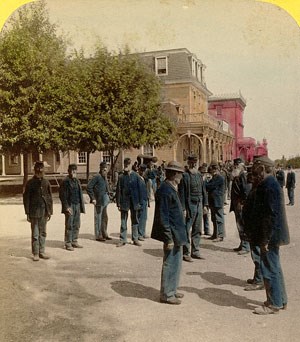

The men at the National Home branches were required to wear uniforms. The United States Army had a surplus of uniforms following the Civil War, so the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers adopted the uniform of the Army as its uniform. Once the surplus ran out, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers continued to have uniforms made. This was required until the Veterans Administration took over management of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1930.

Courtesy of the Dayton VA Archives

The Central Branch held weekly prayer meetings on Sundays. Most branches offered both Catholic and Protestant services for the men and had chapels specifically designed to accommodate the two separate congregations.

The National Home branches held daily court to deal with infractions of members who did not follow the rules. Examples of infractions included bringing liquor onto campus or disorderly conduct. Punishments ranged from detention in the guard house to a fine or being deprived of pay for labor, to the extreme of expulsion from the National Home system. In general, the punishments were applied sparingly; The goal was to provide structure but not have too heavy a hand.

The veterans slept in barracks. Each member had a bed, a chest for his clothes, and a chair. A typical daily schedule for men at the Danville Branch:

| 5 am | Reveille |

| 5:45 am | Bugle call for breakfast |

| 12 noon | Dinner |

| 5:30 pm | Supper |

| 7:30 pm | Fatigue call |

| 7:45 pm | Sick call (Captains report those who are ailing to the surgeon) |

| 9 pm | Drums sound the tattoo |

| 9:30 pm | Bugle taps |

The men ate in large dining halls. The menus for the week were posted in the dining hall. A sample menu from the Eastern Branch:

| Bill of Fare | |

| Sunday Breakfast-Baked beans, brown bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Boiled ham, bread pudding, molasses, bread, coffee Supper-Prunes or crackers, bread, butter, coffee |

|

| Monday Breakfast-Mackerel, potatoes, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Boiled beef, vegetable soup, bread, molasses Supper-Apple sauce, bread, butter, tea |

|

| Tuesday Breakfast-Eggs or fish hash, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Corned beef, potatoes, pickles or vegetables, bread, tea, molasses Supper-Gingerbread, bread, butter, tea |

|

| Wednesday Breakfast-Meat hash, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Roast beef, potatoes, pickles, bread, tea or coffee, molasses Supper-Apple sauce or prunes, bread, butter, tea |

|

| Thursday Breakfast-Baked beans, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Corned beef, potatoes, vegetables or pickles, bread, coffee, molasses Supper-Crackers, bread, butter, tea |

|

| Friday Breakfast-Mackerel, potatoes, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Fresh fish, potatoes, bread, tea, molasses Supper-Gingerbread, bread, butter, tea |

|

| Saturday Breakfast-Meat hash, bread, butter, coffee Dinner-Roast mutton or veal, potatoes, pickles, bread, coffee, molasses Supper-Cheese, bread, butter, tea |

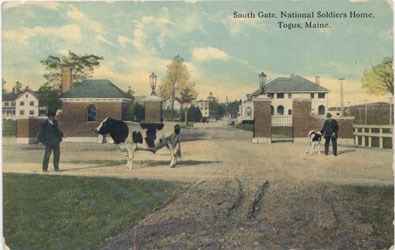

Eastern Branch, Togus, Maine

Kathleen Schamel's personal collection; produced by George W. Quimby of Augusta, Maine around 1910.

The initial intent was for the men to reenter society if possible. To make the transition easier, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers offered education and job training opportunities. The Central Branch opened a school in 1877. The Board of Managers offered to transfer anyone who wanted to attend school to the Central Branch. The school taught arithmetic, algebra, English, grammar, and natural philosophy. The school sought to accommodate physically disabled veterans. For example, teachers taught veterans to write with the opposite hand. By 1881, the school had 82 students and one teacher. The school closed in 1883 because of low enrollment rates. The Board of Managers attributed this to the advancing age of the members.

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers initially tried to develop job training programs, teaching veterans new skills that would accommodate their disabilities. The Central Branch offered bookkeeping and telegraphy training but eventually stopped due to lack of interest. The National Home branches resumed job training programs and vocational rehabilitation programs in the 1920s for World War I veterans.

The National Home branches also provided an early form of occupational therapy. The Board of Managers believed keeping the members engaged in work activities helped “patients to replace morbid ideas with healthy, normal ones to incite interest and ambition and assist to restore a lost or weakened function either mental or physical.” The type of work the men did varied depending on the branch at which they lived. Central Branch had cigar making and stocking-weaving shops. The Eastern Branch had a shoe factory. Men could work at blacksmithing, tinsmithing, knitting and tailoring at the Southern Branch. At all of the branches, men helped to construct buildings, care for grounds, repair buildings, and care for the ill. Most of the branches had farms where men did the farm work as well. The National Home branches sold some of the food but used most of it to feed the men at the branch. The Eastern Branch had 150 acres of arable land. They grew beets, hay, beans, cabbage, and strawberries. By the 1870’s, more than 2,000 men (about one third of the members) had jobs that helped support the National Home branches. The men were able to earn spending money through these programs. At the Eastern Branch in 1879, the wages varied from $5 to $25 per month for each man.

As the population at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers aged, fewer men could engage in these activities; the National Home branches started hiring more outside workers. In the 1920’s, the National Home branches reintroduced some of the programs for the World War I veterans. For example, blind veterans were taught to weave using a special loom. These occupational therapy programs were integral to the success of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, because they gave the members a sense of productivity and provided structure to their daily lives.

Central Branch, Dayton, Ohio

Courtesy of the Dayton VA Archives

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers provided a multitude of recreational activities for members. The Board of Managers wanted the branches to feel like home so the board ensured that members had attractive places to live and plenty of activities to keep them busy, such as libraries, concerts, and zoos.

Campus Design

The Board of Managers planned all but three of the National Home branches’ campuses. The board planned the National Home branches during the time when campuses were designed according to the ideas of the Picturesque Movement. Mountain Home was the only branch not designed in the Picturesque style; it has a Beaux Arts campus layout. The National Home branches were designed like parks, creating a relaxing, enjoyable environment for the members. Central Branch had over 25 acres of flowers and sub-tropical gardens. Battle Mountain Sanitarium planted 1,000 apple, cherry, pear, and plum trees in 1919. Many of the branches had lakes on the campuses. In addition to creating a scenic setting, the lakes provided opportunities for the men to participate in recreational activities such as swimming and boating. The Central Branch had swans on its lakes.

The campuses were constantly being improved and modernized. Battle Mountain Sanitarium added electric lights to the pathways. Some of the branches used surplus or outdated military equipment for decorations. The Danville Branch had several cannons placed around the campus, but they were removed around 1943.

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers provided a wide array of activities and events for members. Most of the National Home branches offered libraries for members to use. The libraries were generally filled with books and newspapers donated by friends and families of the members. Some of the branches received money to fund their library from the Carnegie Library program. The library in Togus had 22 daily newspapers and 115 weekly ones. Overall, the libraries were very popular with the members. On average in 1898, 310 members visited the library daily at the Southern Branch.

|

| Billiards Room, Veterans Clubhouse, at the Central Branch, Dayton, Ohio Courtesy of the Dayton VA Archives |

The National Home branches had theaters for the members to watch plays and other performances. The Horatio Ward Fund supported many of them, and they became known as the “Ward Memorial Theaters.” The annual report from Battle Mountain Sanitarium in 1915 indicates that the entertainment for the year included dramatic performances, vaudeville shows, concerts, readings, and bi-weekly movies. The proceeds from the canteens or home stores at each branch funded these performances. Some branches had amusement halls where activities such as pool and card games were made available to ambulatory patients. The Central Branch offered bowling alleys, bagatelle tables, and billiard tables. The Eastern Branch hosted dances for the veterans and members of the community in the amusement halls, though according to one member, not many of the veterans danced, perhaps only 20 out of 1300 members; however, the families with children in the community would come and dance.

Some branches even had zoos or menageries. The Central Branch had a deer park, bird cage, pond with alligators, a menagerie with a great bear of the Rocky Mountains, buffalo, and a monkey house. Some of the branches offered athletic competitions for the members. Golf courses and baseball fields were available at several of the branches.

Each branch had a Home Band that would play concerts throughout the year. The Home Band provided music for the daily raising and lowering of flags. In the summer, the Battle Mountain Sanitarium had almost nightly concerts; sometimes there would be concerts in the afternoon too. In the winter, concerts were held inside in the chapel or amusement hall building. Band concerts and gramophone music also entertained bed-ridden patients. These concerts and other activities were intended to help keep the veterans’ morale high.

Western Branch, Leavenworth, Kansas

Courtesy of Veterans Affairs

The veterans at the National Home branches were members of a variety of national organizations, whose local chapters often met at clubhouses at the National Home branches. The largest and most influential of these organizations was the Grand Army of the Republic, known as the GAR, which advocated for the rights of veterans. This organization, formed after the Civil War for Union veterans, had considerable political power in local, State, and national politics. The national membership of the Grand Army of the Republic increased from 60,000 to 400,000 during the 1880’s. It also funded the stained glass windows of Lincoln and Grant in the chapel of the Western Branch. Other organizations such as the Union Veteran League and Naval Veterans Association had local chapters at the branches.

Visitors

People from the local community and other visitors took advantage of the recreational opportunities at the National Home branches as well. In the 19th century, it was typical for people to visit institutions such as this as well as insane asylums and prisons. The increased awareness and interest in social reform drew people to these sites. People also visited because the National Home branches had beautiful campus designs with grand buildings located on prominent sites. They were seen as places of tranquility in an increasingly urban and industrial society.

In a guide book for the Eastern Branch, member Wes Weitman claimed that “visitors go into every building, look into every room, and examine every nook and corner.” He and others felt this was good because it held the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers accountable. If care was poor, then the visitors would notice and report it immediately.

Businessmen quickly realized the tourism potential of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Transportation was often provided to the National Home branches. The local manager of Mountain Home built a street car line to go between the branch and Johnson City to bring visitors and members back and forth. In 1904, Pacific Branch was included in a tour of Los Angeles known as the “Balloon Route” that visited sites in West Los Angeles. Amenities for visitors such as restaurants and hotels popped up at many of the National Home branches. The Central Branch estimated 100,000 people a year visited the branch in the mid-1870s. Visiting these sites also helped establish the link between the Federal Government and citizens in a time of very little Federal presence in most areas.