Last updated: January 20, 2022

Article

Contaminants in Surface Water of the Mississippi River

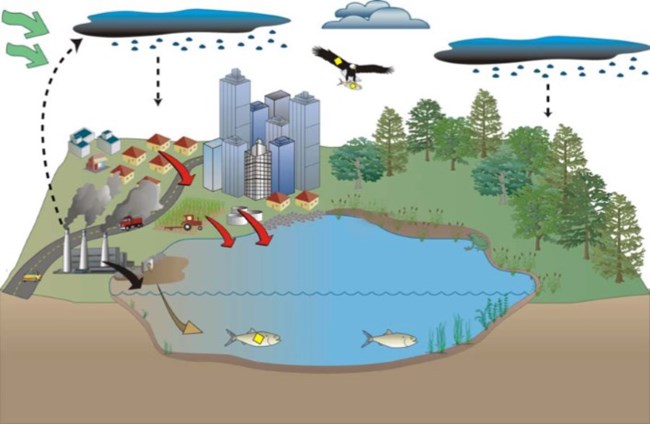

Some contaminants bioaccumulate (increase in concentration and toxicity) as they move up the food chain (yellow diamond in fish and bald eagle).

The land, water, and air of many national parks are affected by pollutants that are transported over long distances in the atmosphere (e.g., mercury), as well as contamination from sources closer to their borders: waste water treatment discharges, agricultural run-off, and mineral exploration and extraction.

Since 2006 we have been monitoring a number of pollutants that are persistent in the environment and bioaccumulate up the food chain by checking pollutant levels in the blood and feathers of nestling bald eagles. In 2013 we began collecting water samples from five locations in the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area (MISS). Samples are tested for over 260 different pollutants that are not necessarily persistent or do not bioaccumulate but have the potential to be toxic at high enough levels. Some of the different classes of pollutants include pesticides, pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and waste water indicators. In 2014, we added seven sites at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore and 21 sites on the East Arm of the Little Calumet River at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Samples from those sites are being analyzed.

The purpose of this study is to develop baseline information about the occurrence of over 260 different contaminants in and near selected Great Lakes Network parks. This is a collaborative project with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Park Service (NPS) Water Resources Division, and six other NPS Inventory and Monitoring Networks.

Hastings

What We’re Finding

Each water sample is tested for numerous contaminants including flame retardants, pesticides, industrial solvents, plastics like bisphenol A (BPA), and commonly used medications for conditions such as pain, diabetes, epilepsy, and depression. Agriculture and waste water treatment plants are a major source of many of these contaminants. The Mississippi River receives a lot of runoff from agricultural lands and effluent from many waste water treatment plants, so it was not a surprise when several contaminants were detected in Mississippi River samples collected in 2013. (Samples collected in 2014 are being analyzed.)

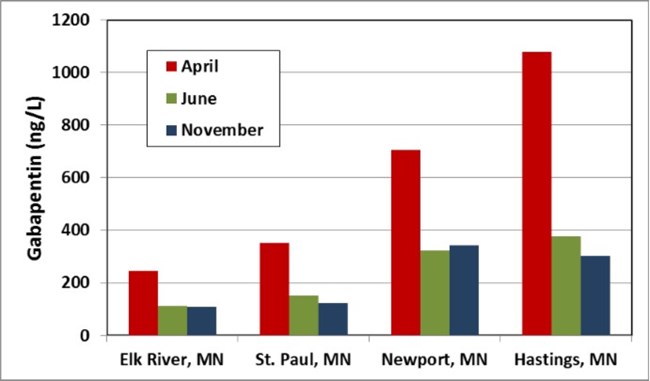

No contaminants were at levels high enough to be a threat to aquatic life or human health according to Minnesota Department of Health standards. However, levels of gabapentin—a drug commonly used to treat seizures and neuropathic pain—were typically an order of magnitude higher than all other contaminants detected across all sites and for the three months when monitoring took place (see graph).

Notably, metolachor—an herbicide commonly used to inhibit the growth of certain grasses and broadleaf weeds in corn, soybean, peanuts, sorghum, and cotton fields—was detected in samples collected at Coldwater Spring during all three rounds of monitoring. Tri (2-butoxyethyl) phosphate—a flame retardant, but also commonly used in floor polishes and as a plasticizer in rubber and plastics—was also detected in the spring water. However, both chemicals were present at extremely low levels (a few parts per trillion). Coldwater Spring and the surrounding area are culturally significant, and the spring itself has been a source of drinking water for hundreds of years.

NPS / Gordon Dietzman

Next Steps

Monitoring contaminants in surface waters helps to identify baseline conditions for previously unmonitored sites and could lead to more intensive monitoring if high levels of contaminants are detected.

To-date, sites have primarily been selected where (1) we expect a relatively high number of detections based on known sources, such as an upstream waste water treatment plant, (2) where contaminants have been monitored in the past so that we can make comparisons over time, and (3) where we hope to make some comparisons between contaminants found in surface waters to those found in fish and wildlife in other studies (e.g., levels of flame retardants). Future monitoring sites will be located on remote lakes where we do not expect any contamination other than what might be deposited through atmospheric deposition.

For More Information

David VanderMeulen

Aquatic Ecologist

david_vandermeulen@nps.gov

Summary by the Great Lakes Inventory & Monitoring Network, October 2014.