By dawn on August 29th, Jackson had placed his three Confederate divisions along the unfinished railroad; the troops extending from Sudley Church to near the Brawner Farm. Jackson's right stretched out to connect with Longstreet's men approaching from Thoroughfare Gap.

"The whole field was covered with a confused mass of struggling, running, routed Yankees." A brigade commander under General Jackson's command

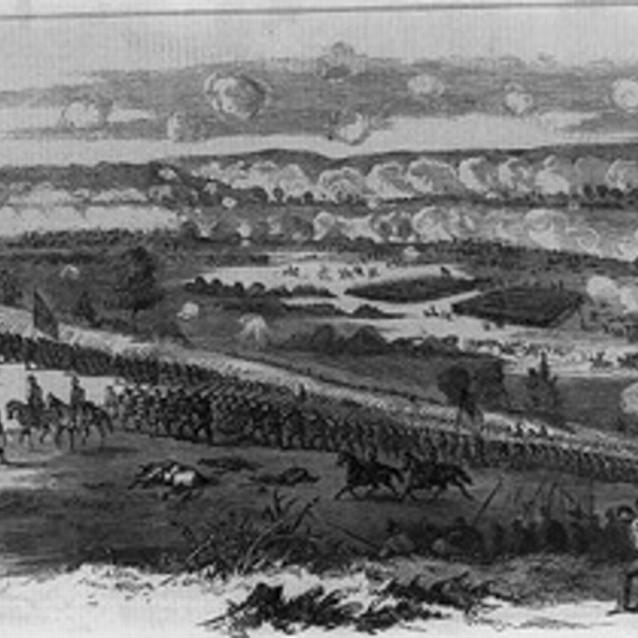

The Unfinished Railroad

Library of Congress

Pope, giving little thought to Lee's objectives, was convinced that Jackson was attempting to flee. He issued orders for all available elements of his army to intercept Jackson and strike him. Pope began the day with a series of uncoordinated and unsuccessful attacks against Jackson's line by Gen. Franz Sigel's corps, moving northwest of the Stone House. Jackson calmly watched the Federal attacks break against his position and waited for Lee and Longstreet.

Around midday, Longstreet's 28,000 men arrived and began to take position on Jackson's right - largely south of and nearly perpendicular to the turnpike. Although Lee's immediate impulse was to attack, Longstreet wanted to wait. There were unknown numbers of Federals threatening his right, and he prefered receiving an attack to delivering one. Unsure of how many of McClellan's army had reinforced Pope, Lee consented.

At 2:00 p.m., Heintzelman's corps reached the battlefield to continue to assault Jackson's position. Gen. "Fighting Joe" Hooker's division relieved Sigel's depleted brigades as Pope continued to simply throw his available troops incrementally at the railroad embankment to keep Jackson at least occupied or at best break Jackson's line east of where a back country lane crossed the grade. Had all the Union troops attacked Jackson at once, the story might be quite different. Great holes were torn in Jackson's left and center, but skillful shifting of Confederate reserves drove the Union troops back with heavy losses. At about 3:00 p.m., Gen. Cuvier Grover's brigade of Hooker's division made a gallant bayonet attack, losing 25 percent of his men. Col. James Nagle's brigade also created a big gap, but his troops were driven back with losses nearing 40 percent.

Meanwhile, Pope remained confident that Longstreet's Confederates were nowhere near the battlefield and still believed that Jackson was attempting to retreat. Based on this misunderstanding, Pope planned another assault on Jackson's position for the next day with Gen. Fitz John Porter's corps at its head. Gen. John Reynolds' division would support the attack and other Union divisions under McDowell were assigned to pursue Jackson when he retreated.

That night Pope wired Washington that he had achieved a great victory. Tomorrow he would pursue and finish off Jackson; or so he thought.

Porter's Attack

National Archives and Records Administration

Preparations took time, and it was past noon on the 30th before Porter had his troops assembled and ready to move. Some 7,000 Union men in a thick blue battle formation about a half mile wide began to push slowly west and north. Unfortunately for them, they were moving into the jaws of a trap.

The Confederate army was deployed in a large obtuse angle, the apex being just north of the turnpike. The left, or north, side was held by Jackson, still firmly posted behind the railroad grade. Though weakened, he still possessed some 18,000 formidable infantry. Concealed on the right, or south, side of the angle was Longstreet with 28,000 fresh soldiers, ready to fight. Longstreet had positioned a massive concentration of artillery in the angle between the two wings. It was into these two jaws that McDowell's "pursuit" was moving.

South of Groveton, Reynolds' men almost immediately encountered enemy fire. Reynolds, seeing evidence of Longstreet, was sure that he faced a large Rebel force extending beyond his left. McDowell ordered Reynolds to shift his three brigades back to the vicinity of Chinn Ridge to guard against any threat to the Federal rear.

For the Union cause it was a tragic blunder because it created a big gap in the Union lines immediately south of Groveton and left Porter's left flank dangling and naked. Despite Porter's better judgment, he launched the attack around 3:15 p.m. From the cover of the woods east of the Groveton-Sudley Road, about 5,000 men surged across the road, over a fence, and into open fields. Confederate artillery, concentrated on a ridge a half mile to the west, opened a deadly fire down the length of the Union lines. Thirty-six guns rained case shot and shrapnel over the field. Still the Federals swept onward, almost to the crest. Men on both sides reloaded and fired at a frenzied pace. Jackson was forced to call for reinforcements from Longstreet. In a desperate moment, some of his men, out of ammunition were reduced to throwing rocks at Federals less than 20 yards away. Longstreet responded to Jackson's call for support with additional artillery fire from a battery he deployed along the turnpike.

But it was the Northerners who withered. They could neither pierce Jackson's defenses or remain where they were in the open. Retreat was the only sensible choice. Porter's units were beaten and fell back in a rush. As one of Jackson's brigade commanders described it, "the whole field was covered with a confused mass of struggling, running, routed Yankees."

Part of a series of articles titled The Vortex of Hell.

Previous: August 28, 1862

Next: The Attack Continues

Last updated: February 4, 2015