The longest irrigation tunnel in the world when it was dedicated in 1909, Colorado’s GunnisonTunnel was an engineering marvel. The 5.8-mile tunnel cut right through the sheer cliffs of the famed Black Canyon, taking water from the Gunnison River and funneling it to the semiarid Uncompahgre Valley to the west.

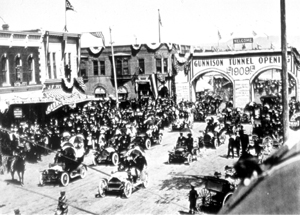

It was none other than President William Howard Taft, vacationing in the West, who dedicated the tunnel in September of 1909. What a grand day it was for the little town of Montrose, which welcomed the president with a parade and a two-story-high memorial arch stretching across Main Street. No doubt the president was impressed, for the Gunnison Tunnel was built, as he put it, in the “incomparable valley with the unpronounceable name.” Uncompahgre (Un-come-PAH-gray) is a Ute Indian word meaning “hot water spring,” while Taft’s “incomparable valley” was the raw beauty of a Colorado landscape framed by plateau and the towering San Juan Mountains.

Flowing through the valley’s heart is the Uncompahgre River, long utilized by the Ute Indians until a mining boom in the 1870s and a tide of American settlers led to their removal from western Colorado. The new settlers, as had the Utes, looked to the Uncompahgre for sustenance; in the arid West, water was nearly as good as gold. Settlers dug canals and formed ditch companies, believing that the river with the unpronounceable name contained enough water to irrigate 175,000 acres. But the Uncompahgre proved unreliable. By 1890, with fewer than 30,000 acres cultivated, water shortage spurred new schemes for irrigating the valley.

Legend has it that a local farmer and one-time miner, Frank Lauzon, had a dream in which he came up with an idea: dig a tunnel from the more substantial Gunnison River, which roared in the Black Canyon beyond Vernal Mesa, and divert water to the Uncompahgre Valley. In 1900, local rancher John Pelton set out with a party of four men to run a line of elevation down the famed Black Canyon of the Gunnison River and determine whether a tunnel was feasible. The men put their two, heavy wooden boats into the Gunnison, only to crash one of them against the rocks, sending splinters and supplies downstream. Though their mission was a failure, it generated interest in the tunnel and, the next year, Abraham Lincoln Fellows of the U.S. Geological Survey and William Torrence of the Montrose Electric Light and Power Company set out with rubber air mattresses and waterproof bags. They emerged from the precipitous gorge nine days later with their lives as well as photographs and locations of the best sites to tunnel and build a diversion dam.

In 1901, the State of Colorado appropriated $25,000 to start the tunnel, but only 900 feet were driven before funds ran out. The next year, after Congress passed the Reclamation Act of 1902, the project moved forward again. The Reclamation Act committed the Federal Government to construct irrigation works--dams, reservoirs, tunnels, and canals-–to irrigate arid and semiarid lands in 16 western states and territories, including Colorado. With the formation in 1903 of an association of landowners obligated to pay back the government’s cost of construction, the Gunnison Tunnel (part of the Uncompahgre Project) became one of the first five projects undertaken by the new Bureau of Reclamation (originally known as the U.S. Reclamation Service).

The undertaking proved difficult and gargantuan. The plan called for workmen to dig two portals through Vernal Mesa--one would begin on the canyon floor and the other in the valley beyond-- with the goal of meeting in the middle. But first they had to scrape a road across the rugged mesa to the Gunnison River, roaring some 2,000 feet below the canyon rim. So tall were the canyon walls that they could tower over the Empire State Building. So steep was the road from rim to river that it descended in places at a 30 percent grade. Drilling equipment had to be eased down on skids, and it wouldn’t be until 1932 that an automobile succeeded in getting to the river, although it had to be pulled back up by a team of horses.

Seeping water, poisonous gasses, excessive temperatures, and the presence of clay, sand, shale, and a fractured fault zone complicated the drilling, which had to be halted for six months at one point so a ventilation shaft could be driven into the mesa. Although as many as 500 men were employed with good pay, few rarely stayed on the job for more than a few weeks. A cave-in took six lives, an explosion and smoke 12 more, and a falling boulder another. Many workers, some with families, lived near the West Portal in a temporary town called Lujane. At the other side of the mesa, clutching the slopes of the canyon, a community named East Portal also thrived. Both towns had amenities, including a dining hall, school, hospital and post office. Before the tunnel was done, technological advances made the work safer and easier. Jack hammers fed by a compressor replaced hand-turned drill bits, and dynamite replaced black powder for blasting.

When tunnel construction began in 1905, survey measurements had to be precise, a difficult task in the rough terrain. Using geometry, engineers were able to draw a direct line through the mesa by sketching a series of polygons and linking together the hypotenuse, or long side of the right-angled triangles. On July 6, 1909, the tunnel bore--11 feet wide by 12 feet high--was “holed through” as workers digging from the West Portal and those digging from the East Portal met in the middle.

The Gunnison Tunnel, which is a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. It has had a dramatic impact on the Uncompahgre Valley. By 1923, the valley’s population had doubled to more than 6,000, and its irrigated acres mushroomed from 37,000 acres in 1913 to 64,180 acres in 1933. Today, with its corresponding system of canals, laterals, diversion dams, and the Taylor Park Reservoir, the tunnel project irrigates nearly 76,300 acres, making the Uncompahgre Valley rich in alfalfa, wheat, corn, oats, potatoes, beans, onions and fruit--apples, pears and cherries. Beginning in the 1960s, project farmers started growing Moravian malting barley, used for the manufacture of Coors beer.

In 1991, the Bureau of Reclamation’s Project Office Building, built in conjunction with the Gunnison Tunnel, was also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Constructed in 1905 at 601 N. Park Ave. in Montrose, the two-story, wood frame structure has been occupied since 1932 by the office of the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association and is a good example of the Foursquare building type. The Gunnison Tunnel celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2009, and is still in use today.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 3, 2018