Freelan Oscar (F. O.) Stanley made a career putting water to work. Famous for co-inventing the steam-powered Stanley Steamer auto in 1897, he employed water yet again in 1909 to build a hydroelectric powerplant on the Fall River in Estes Park, Colorado. In 1903, Stanley had moved to little Estes Park, 65 miles northwest of Denver, to combat his tuberculosis. The dry mountain air and plentiful sunshine aided his recovery. In 1909, realizing the town’s need for tourist accommodations that matched its majestic scenery, he built the luxurious Stanley Hotel (later made famous as the inspiration of Stephen King’s 1977 thriller, The Shining). Desiring a world-class resort, Stanley built his powerplant to equip the country’s first “all-electric” hotel with wired heating, cooking, and lighting. The Town of Estes Park soon requested electricity for its street lights, and residents ordered the modern service for their homes. Hydroelectricity’s novel presence in Estes Park evolved, nearly 40 years later, when the Bureau of Reclamation also employed the town’s rugged terrain for a larger powerplant as part of its Colorado-Big Thompson Project. The Estes Powerplant, completed in 1950, was one of five new powerplants in a complex system that altered the region’s steep hills with tunnels, conduits, reservoirs, and hydropower plants to generate electricity as water for irrigation flowed down the east face of the Rockies.

Although the Colorado and Big Thompson rivers rise within miles of each other in the peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park, the Continental Divide splits their basins, charging the Colorado to flow west, and the Big Thompson to flow east. Named for these two rivers, the Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado-Big Thompson Project’s principal purpose was to divert a portion of the waters of the Colorado River from the West Slope of the Rocky Mountains to the Big Thompson River on the East Slope to stabilize agriculture on northeastern Colorado’s high plains. Delivering water to land already developed for farming was a departure from Reclamation’s earlier projects that typically functioned to reclaim the raw desert.

By the early 1870s, ambitious settlers of eastern Colorado’s high plains—an area labeled the “Great American Desert” by explorer Stephen Long—had completed extensive canal networks, inaugurating decades of agricultural growth east of the Colorado Rockies, in a region known as the Front Range. By the early 1890s, however, private interests identified Colorado’s paradox: more farmland than water east of the Rockies, and more water than farmland in the western half. They dreamed of transporting West Slope water to the east side, but the cost was too great.

As early as 1905, the U.S. Reclamation Service, established to develop irrigation projects in the West, surveyed trans-mountain diversion routes in Colorado, but the report collected dust as Reclamation instead pursued the Grand Valley Project in western Colorado. Despite the water shortage, private irrigation schemes continued along the Front Range, and the population more than doubled between 1900 and 1910. By that time, however, the river flows could not support the growing region. From 1925 to 1933, northeastern Colorado farms suffered a severe drought, receiving only a third of the irrigation water they needed, and $42 million in crops withered away. Regional economic stagnation loomed, and farmers on Colorado’s wind-swept plains looked longingly toward the Colorado River’s seemingly untapped waters west of the Continental Divide.

The dry plains motivated Alva B. Adams, a U.S. Senator from Colorado, to push for a Federal trans-mountain diversion project. However, the proposal to divert Colorado River water to eastern farms sparked controversy, especially from West Slope residents who felt diverting the river threatened their region’s future growth and stability. Adams enlisted the help of the Union Pacific and Burlington railroads, Great Western Sugar Company, and city chambers of commerce along the Front Range. That arsenal of political and corporate power supported the 1934 organization of the Northern Colorado Water Users Association, which became the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District (NCWCD) in 1937, and Reclamation’s partner for the project. Congress and the resilient project opponents, led by U.S. Congressman Edward T. Taylor from Colorado, eventually reached a compromise—the project would commence with a West Slope dam, reservoir, and powerplant at Green Mountain to store replacement water for future West Slope use. (For more information about the Green Mountain Powerplant, the project’s only powerplant fed by a dam and reservoir system, rather than by penstocks, see the Green Mountain site despriction). Then, Reclamation would continue with the construction of its labyrinth of pipes and reservoirs to bring the water east. In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the Colorado-Big Thompson Project.

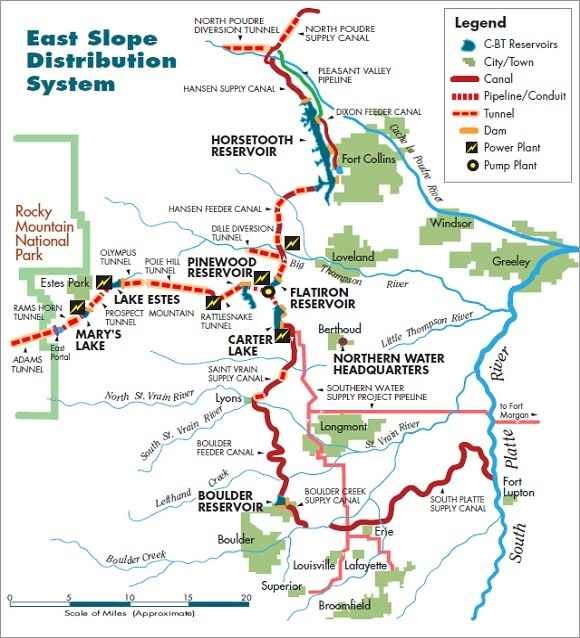

The Colorado-Big Thompson Project took 19 years—from 1937 to 1958—to finish constructing all components. Costly snags required redesign of the trans-basin, trans-mountain diversion structures, and war-time inflation ballooned the original project estimate of $50 million to $162 million, compelling Reclamation to expand its original plan for one powerplant to six—the original West Slope plant at Green Mountain, plus five on the East Slope. The final design resembles stair steps; a step going up the West Slope of the Rocky Mountains, then four steps down the East Slope. On the West Slope, the water is pumped up from a lower reservoir to a higher one, then through a 13.1 mile tunnel, named the Alva B. Adams Tunnel, which pierces the Rockies at an elevation of 8,300 feet above sea level. On the East Slope, tunnels, siphons, conduits, and canals carry water down the mountains and across land, where the falling water runs through five powerplants to generate electricity. Water is then released into the Big Thompson and other rivers as well as into canals for irrigation use. In all, water drops about 2,800 feet from the Adams Tunnel’s eastern portal to the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, making it a situation ideal for hydroelectric generation.

In 1947, work on the project’s west-side dams and canals was near completion and the Adams Tunnel under Rocky Mountain National Park had been bored and lined with concrete. Crews then began construction of the Estes Park Aqueduct and East Slope power system. By 1949, however, the unfinished Mary’s Lake Powerplant and Estes Powerplant stood in the way of a complete link between the Adams Tunnel and the Big Thompson River. Farmers on the Front Range waited in anticipation, as they had for nearly two decades, for supplemental flows from the Colorado River.

The next year, the finally complete Estes Powerplant began operation. The rectangular, reinforced concrete structure and its switchyard are located on the eastern edge of Estes Park, at the west end of Lake Estes. The Colorado River’s first stop upon exiting the Adams Tunnel’s east portal was Marys Lake and Powerplant. Then, it flowed through underground pipes to the Estes Powerplant, where it spun three 15,000 kilowatt units, then exited through one of two routes: some discharged into Lake Estes (which is 97 percent Colorado River water), where it flowed past Olympus Dam into the Big Thompson River; the rest discharged to a series of tunnels toward the southern “power arm,” where it generated electricity at three stops—Pole Hill, Flat Iron, and Big Thompson powerplants.

Up at the Estes Powerplant, electrical engineers had to figure out how to send power generated there to the West Slope to supplement Green Mountain power used to operate the pumping stations that sent water up and over the Continental Divide. The obvious route required a giant, mountain-climbing transmission line over the Rocky Mountains. However a creative contractor put in a proposal to instead build a 69,000 kilovolt (kV) “submarine cable” line that would be strung through the Alva B. Adams Tunnel under Rocky Mountain National Park. Persuaded by the clear advantages of a line that would not need to scale the Continental Divide, Reclamation chose this option, creating two-way traffic in the tunnel as power zipped west to pump water that flowed back east, which in turn generated more electricity that returned west.

The majority of electricity from the Estes Powerplant takes a second route, firing into the electrical grid, where it becomes available for purchase—earning revenues that cushioned the project’s 9-digit price tag. Along with easing the financial burden for the project’s water users, hydroelectricity from the Estes Powerplant helps steady the grid, stabilizing power delivery and prices. The Colorado-Big Thompson’s power system generates over 750 million kilowatt hours annually—enough to power over 58,000 homes a year. Some of the energy fuels the West Slope pumping plants, while most is marketed by the Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) and sold to users in Colorado, eastern Wyoming, and western Nebraska.

The Colorado-Big Thompson Project, with the Boulder Canyon and Colombia Basin Projects that constructed Hoover and Grand Coulee dams, respectively—was one of several large New Deal-era projects that served to reorient Reclamation into a multi-purpose agency. The Colorado-Big Thompson Project also represents Reclamation’s evolution into an agency that aided already established agricultural communities to grow and have a more reliable water supply, rather than developing new farming opportunities in the West. (In 1957, in the first full year of operation, Colorado-Big Thompson water serviced 720,000 irrigated acres, earning project farmers a $68.7 million harvest, with 98 percent of the water serving northern Colorado farms.) This role continued to morph as Reclamation’s mission changed from construction of great water projects to operation and maintenance of its current water storage and delivery facilities. Today, the Bureau of Reclamation’s mission is to “manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public.”

The Colorado-Big Thompson Project was determined eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places for its significance as one of the largest and most complex systems ever to be built by the Bureau of Reclamation. In 2010, the Estes Powerplant was determined to be a contributing feature of a potential sub-district within the larger Colorado-Big Thompson trans-mountain diversion system. The powerplant is located on the eastern edge of Estes Park on the upper end of Lake Estes, which serves as the afterbay for the powerplant. The reinforced concrete structure is relatively unadorned, however the 24 panels of glass blocks, 12 on the north side and 12 on the south side, provide architectural interest while also supplying natural lighting for the interior, where three generator/turbine units are housed. These units are fed by three, 78-inch diameter, plate steel penstocks, 4,000 feet in length—a 600 foot-long portion of the penstocks run above ground on a hill southwest of the plant.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017