Coho salmon live in several of the coastal streams within the Golden Gate National Recreational Area and Point Reyes National Seashore. Because coho are an endangered species, the National Park Service (NPS) is responsible for monitoring and protecting these populations.

Michael Reichmuth / NPS

Olema, Redwood, and Pine Gulch Creeks in Marin County all support populations of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch); however, spawning stocks along the central California coast are only at about 1% of historical levels. Habitat loss from urbanization, dam construction, logging, water withdrawals, and stream channel alterations have contributed to their decline, as has over-harvest, climactic changes, and periods of poor ocean productivity.

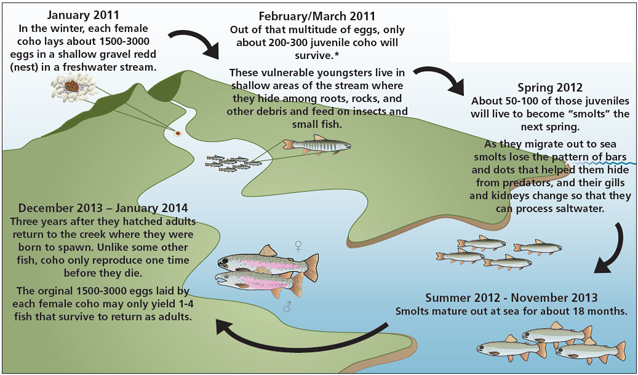

Figure 1 illustrates the coho’s complex fresh and saltwater lifecycle. A female fish born in 2011 will not return to lay its own eggs until about 2014—a full three years later. Because females are three years old when they spawn, every three years represents a distinct “cohort”, or different group of fish that are living on the same three year cycle together. Three cohorts live in San Francisco Bay Area streams: Cohort 1: born 2004, 2007, 2010, etc... Cohort 2: born 2005, 2008, 2011, etc... and Cohort 3: born 2006, 2009, 2012, etc... Having three distinct groups makes following coho population dynamics a bit tricky. The number of coho in a given year does not reflect what happened the previous season, or even the state of the entire population, but what happened three years ago. It also does not predict what will happen the following year, but instead what might be expected in three years.

*These numbers are estimated survival rates for coho in an average to good year. Numbers may be lower if big storms wash away eggs and juveniles, or poor ocean conditions make it difficult for adults to find food.

Monitoring Program

NPS monitors each cohort of coho salmon throughout their entire lifecycle to track population trends and evaluate the effects of restoration activities.

In 1997, NPS staff and volunteers began monitoring coho salmon in Redwood, Olema, Pine Gulch, and Cheda Creeks. The Marin Municipal Water District surveys Lagunitas and San Geronimo Creeks and Devil’s Gulch. The Salmon Protection and Watershed Network monitors tributaries of San Geronimo Creek. Combined, these programs have provided critical information about the coho in these streams.

The NPS monitoring program is designed to address the following questions:

- What are the trends in coho abundance and distribution during their different life stages?

- Have the size and health of these fish changed over time?

- Is the park meeting their mandate for salmon habitat protection?

- How are habitat restoration efforts affecting coho recovery?

Year-round monitoring (below) captures coho population dynamics at each life stage, and also for each cohort over time. For example, comparing the number of juveniles to how many smolts migrate to the ocean the next year provides an estimate of juvenile survival rates. How many of those smolts return from the sea 18 months later to spawn gives a measure of ocean productivity and survival. Finally, counting the numbers of redds produced by these spawners indicates their level of reproductive success.

Michael Reichmuth / NPS

Spring Smolt Trapping

From March to June, temporary traps capture a sample of salmon smolts migrating out to sea. Biologists and volunteers count, weigh, and measure the fish before releasing them. This information is used to estimate the number and size of smolts in the stream, and can be compared across multiple years to track the size and condition of each year class. Size is especially important because larger smolts have a better chance of surviving to adulthood.

Jessica Weinberg McClosky / NPS

Summer Juvenile Survey

Between July and October, scientists and volunteers use snorkel surveys to count juveniles hiding under vegetation and stream banks. These surveys give an estimate of the number and location of young fish in the stream. This estimate is then calibrated by electrofishing—a technique that uses electricity to temporarily stun the fish allowing for safe capture and release. Some of the fish are weighed and measured to determine their health. The size of juveniles is an indicator of the stream’s habitat quality and food availability.

Jessica Weinberg McClosky / NPS

Winter Spawner Survey

From November through February, returning coho salmon adults (spawners) and redds (nests) are counted. This information can then be combined with data from other years to help illuminate long-term trends in distribution, abundance, and size of spawning coho.

Current Status

Though each of the three cohorts and each of the monitored creeks show distinct population patterns, overall numbers of salmon on the West Coast are declining.

While there are many reasons for this decline, two of the largest contributors are stream and floodplain habitat loss, which affect eggs and young fish, and La Niña years that affect ocean conditions and reduce the amount of food available to adults. While there is not much NPS can do about what happens out at sea, they have undertaken a number of restoration projects to improve coho habitat on the lands that they manage. To learn more about these projects see Coho Salmon: Habitat and Climate Matter.

Prepared by the San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program, 2011.

Last updated: February 23, 2018