Last updated: December 14, 2023

Article

Fifth National Climate Assessment

Alaska Chapter

The Fifth National Climate Assessment is the U.S. Government’s preeminent report on climate change impacts, risks, and responses. It is a congressionally mandated interagency effort that provides the scientific foundation to support informed decision-making across the United States. This article presents the findings and highlights from the Alaska chapter, published in 2023.

Alaska is warming two to three times faster than the global average. The physical and ecological effects of warming are evident around the state. Glaciers are shrinking, permafrost is thawing, and sea ice is diminishing. The growing season is longer, and fish, mammals, birds, and insects have increased in numbers in some areas and dropped sharply in others. This combination of environmental effects has far-reaching consequences for people statewide.

Note: This article presents verbatim, but abridged, content from the report. For more information and references, please go to the full report.

Our Health and Health Care Are at Risk

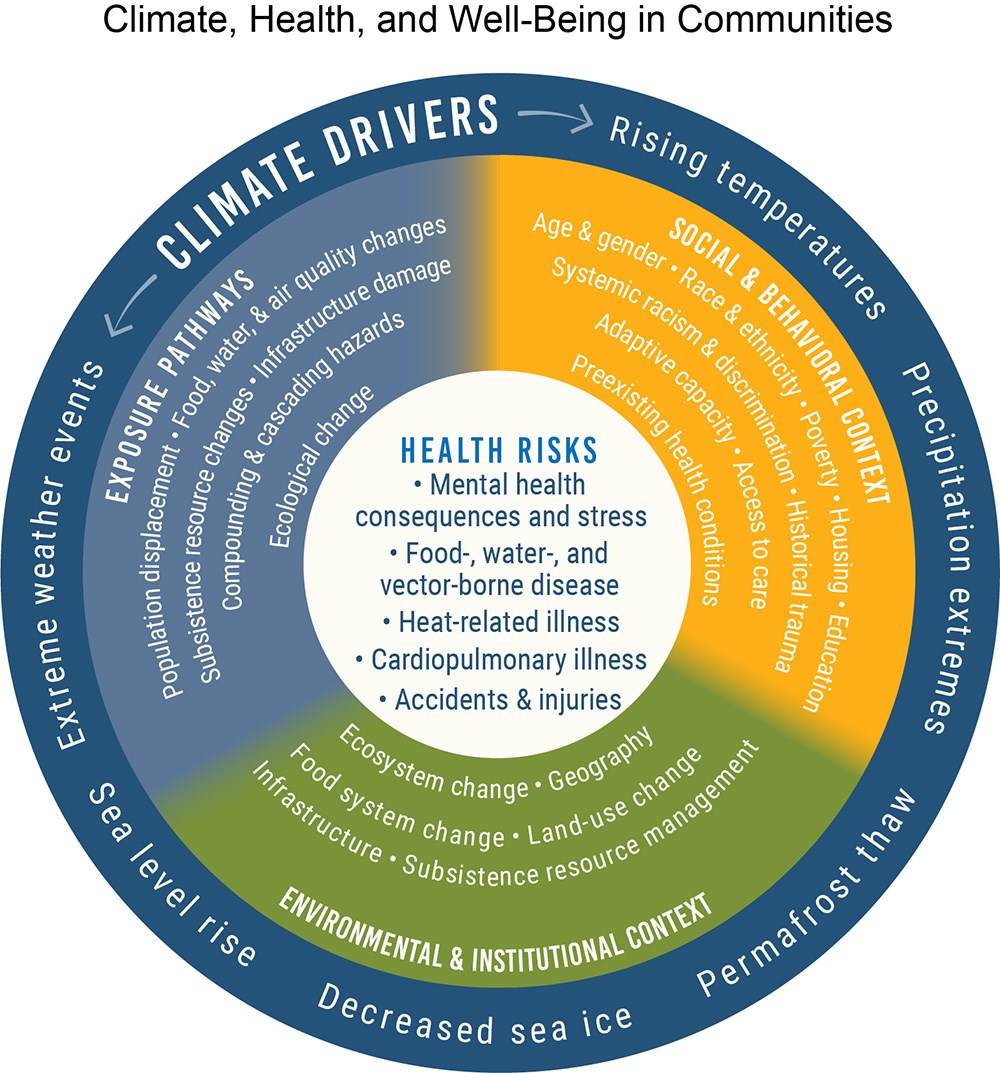

Health disparities in Alaska, including access to healthcare and health outcomes, are exacerbated by climate change. The well-being of Alaska residents will be further challenged by climate-driven threats and by emerging diseases. Improving health surveillance and healthcare access statewide can increase resilience to events that threaten public health.

Many Alaskans, particularly Alaska Native Peoples, have a distinct connection to and understanding of the natural environment and depend on the land, sea, and natural resources for their economic activities, food security, health, culture, and overall well-being. This close connection to local ecosystems, combined with the geographical isolation of many communities and their resulting distance from healthcare and other services, creates a population particularly vulnerable to health impacts from the local effects of a changing climate yet also fosters self-reliance and resilience. READ MORE

Balbus, J., et al., 2016: Ch. 1. Introduction: Climate change and human health. In: The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. U.S Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.

Our Communities Are Navigating Compounding Stressors

Climate change amplifies the social and economic challenges facing Alaska communities. Resource shifts, coastal and riverbank erosion, and disproportionate access to services will continue to threaten the physical and social integrity of these communities. Increased adaptation capacity and equitable support have the potential to help rural and urban communities address Alaska’s regionally varied climate-driven threats.

Climate change affects all Alaska communities but in regionally distinct ways for urban areas compared with rural, predominantly Alaska Native, places. Lacking road connections, Alaska’s rural areas are more remote than rural areas in the Lower 48. About 79% of Alaskans live in urban areas. This concentration creates challenges for the development and maintenance of infrastructure in rural areas where economies of scale do not exist. For example, there are large disparities in exposure to the effects of climate change and inequities in access to resources and capacity for responding to those effects.

Both urban and rural communities face significant infrastructure and access challenges related to permafrost thaw and erosion. Rural communities facing relocation are among the hardest hit, as are low-income populations in urban areas. In the Fairbanks North Star Borough (FNSB), a comparison shows that the average value of residential land with shallow permafrost soil is about 40% the average value of residential land borough-wide. Low-income populations in FNSB disproportionately reside in homes on or near permafrost-affected soils and are thus disproportionately impacted by damage resulting from permafrost thaw.

Food security is a major priority for the state of Alaska. The vast majority of food Alaskans purchase is grown elsewhere, arriving via long supply chains. COVID-19 highlighted the fragility of the state’s food supply and serves as an analog for the potential impacts of climate-related environmental shocks. During the pandemic, backlogged ports and restrictions on overland trucking through Canada made food and other essentials difficult to obtain. Remote regions of Alaska were among the hardest hit by supply chain disruptions. Given the high cost of food and the vulnerability of rural transportation networks, subsistence activities (including hunting, fishing, and sharing) are critical in rural Alaska. This is especially true for Alaska Native communities, as well as for many non-Native and urban residents. About 45.4 million pounds of wild food were harvested in Alaska statewide in 2017, with an estimated replacement value of $262–$523 million (in 2022 dollars), not counting their cultural and spiritual value. Yet the success of subsistence harvests is influenced by numerous external and climate-driven factors. These include shifting distribution, abundance, and migratory patterns of fish, birds, and mammals that affect availability to hunters and fishers; rising fuel costs that increase the cost of hunting, fishing, and gathering activities; and changing weather, flooding, and dangerous ice that increase risks to those engaged in these practices. READ MORE

Our Livelihoods Are Vulnerable Without Diversification

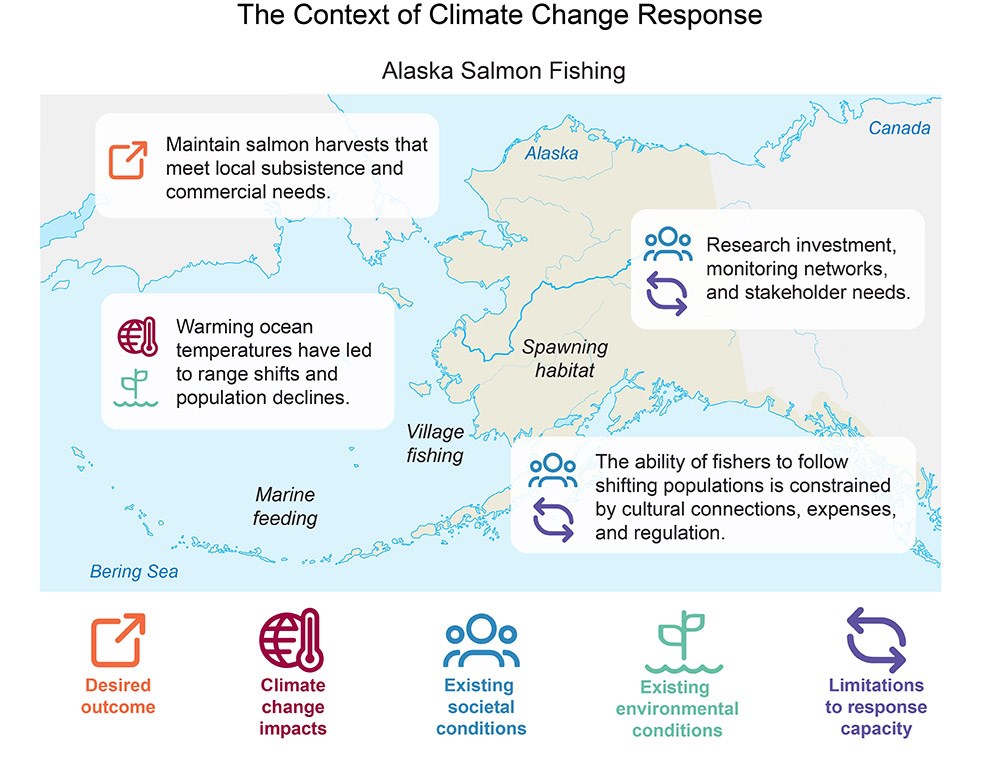

Livelihoods, especially those dependent on natural resources, are at risk around Alaska. While advancing climate change has contributed to the collapse of major fisheries and is undermining many existing jobs and ways of life, it may also create some opportunities related to adaptation and response. Economic diversification, especially expansion of value-added industries, can help increase overall livelihood options.

Many jobs in Alaska are affected directly or indirectly by climate change—through alterations in abundance and distribution of fish species, through changes in access to lands and waters dominated by permafrost and ice, and through the cascading effects of a changing economy. Sustaining healthy livelihoods and ways of life in Alaska involves more than wages and salaries. Traditional cultural practices outside the cash economy include the harvest and sharing of fish, wildlife, and berries. Climate-driven changes to lands and waters, along with societal trends such as greater adoption of mainstream food practices, can reduce opportunities for subsistence harvests and thus affect cultural, nutritional, and spiritual well-being, especially for Alaska Native communities.

Climate change has negatively impacted the condition, growth, survival, reproduction, population biomass, and harvest of marine fishes, salmon, and crab. In addition, groundfish and crab distributions have shifted northward or offshore, following colder water, and the timing of groundfish spawning and salmon spawning migration has been altered. Salmon are in double jeopardy because climate affects both their freshwater and marine habitats. Changes in spawn timing will require changes in survey timing and stock assessments. Changes in fish and crab distribution will require adjusting survey locations and area-based management measures. Fishers will need to adjust the timing of harvest or switch to other harvest targets. Local economies can be resilient through income diversification such as participating in several different fisheries.

Ocean Conservancy

Warmer temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns also affect the distribution of and access to terrestrial and marine mammals. Increasingly volatile storms and changing ice and water levels are of immediate concern because they threaten the availability of wild foods, as well as safe access to these subsistence resources by boat, snowmobile, or all-terrain vehicle. Shorter durations of suitable conditions for spring marine mammal subsistence hunting in the Arctic due to loss of sea ice will require adaptation of traditional hunting practices. On land, more frequent rain-on-snow events can increase stress and mortality for wildlife, reducing availability. Migratory patterns for caribou and other species are also changing, again affecting access for hunters.

Berries are of high nutritional and cultural importance to Indigenous and rural communities. A recent survey indicated that, statewide, berry harvests have become less reliable due to declining abundance or increased variability. Changes in precipitation and temperature are expected to continue to affect berry production, and they may also impact pollinators. READ MORE

Our Built Environment Will Become More Costly

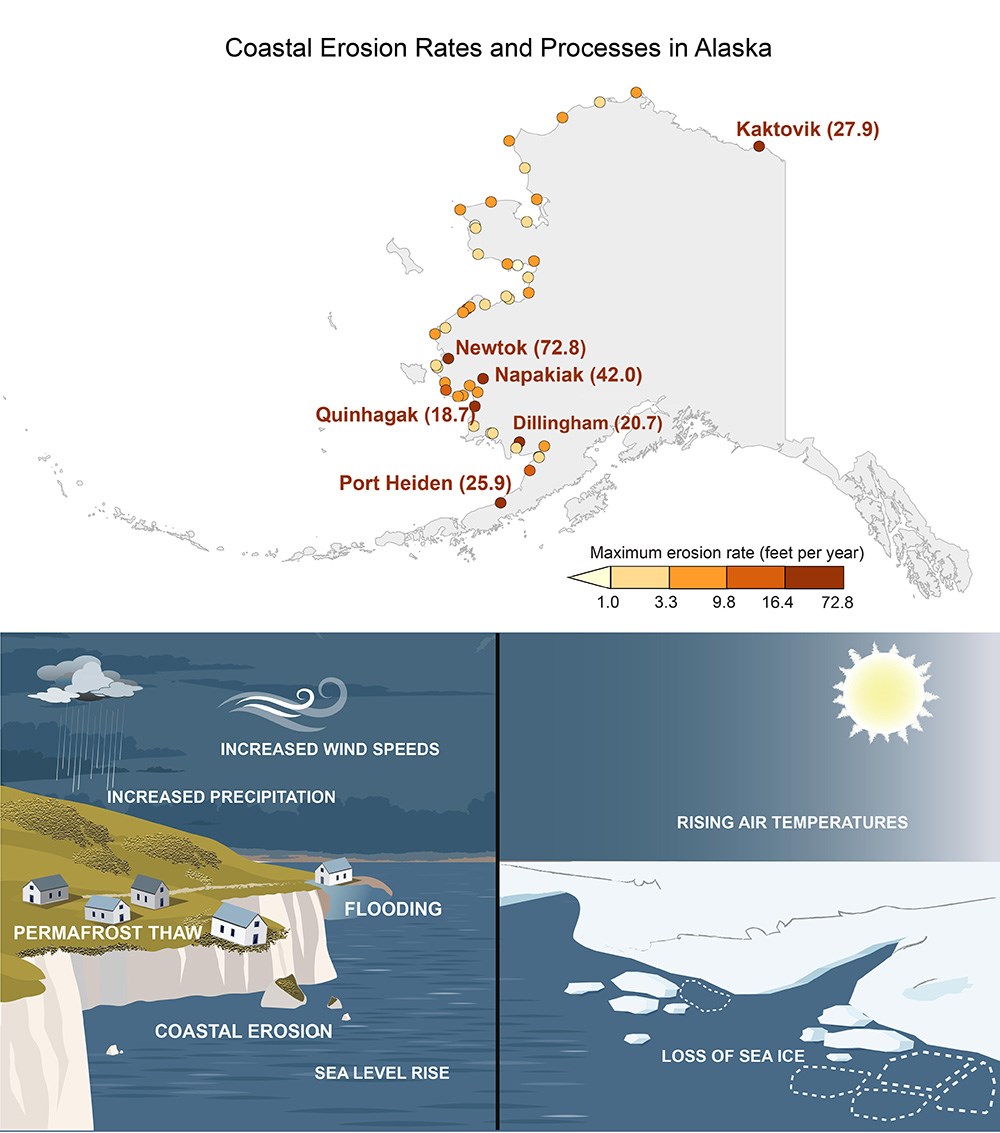

Much of Alaska’s infrastructure was built for a stable climate, and changes in permafrost, ocean conditions, sea ice, air temperature, and precipitation patterns place that infrastructure at risk. Further warming is expected to lead to greater needs and costs for maintenance or replacement of buildings, roads, airports, and other facilities. Planning for further change and greater attention to climate trends and changes in extremes can help improve infrastructure resilience around Alaska.

Buildings and other infrastructure throughout Alaska are at risk from flooding, erosion, and permafrost degradation. More than half of Alaska's communities are at the highest threatened level according to the most recent statewide report. For example, on Alaska’s northern and western coastlines, communities face between 1 and 72.8 feet of erosion per year. Recent progress has been made to understand local flood and erosion vulnerability for Alaska communities by determining erosion ratesand historical flood heights; however, these reports are not available for all communities. Given that 80% of Alaska is underlain by permafrost, regional infrastructure damages are projected to be high. Modeling erosion’s dependence on permafrost integrity and persistence has been an emphasis of recent research. However, the widespread lack of permafrost presence assessments, and the degree to which local erosion depends on permafrost responses, is a key source of uncertainty in forecasts for specific Alaska communities. Extensive coastal and riverbank erosion has also exposed old gravesites in western Alaska, and permafrost is integral for cold storage in many Alaska Native communities and camps.

Overbeck et al. 2020: Shoreline Change at Alaska Coastal Communities. Report of Investigation 2020-10. Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys (top) University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska Arctic Observatory and Knowledge Hub (bottom).

Alaska Native communities face an estimated $4.8 billion (in 2022 dollars) in costs to infrastructure from environmental threats over the next 50 years. These costs may be significantly underestimated due to limitations in current model-based approaches, as well as to the omission of dispersed but culturally vital infrastructure such as fish camps. Various assessments have been completed to try to determine the cost of environmental changes to communities. The costs of responding to climate change are unevenly distributed, with rural areas facing greater costs and few benefits, in contrast to urban areas that will realize some benefits such as reduced heating expenses and where the costs of infrastructure maintenance will be spread over a much larger population base. READ MORE

Our Natural Environment is Transforming Rapidly

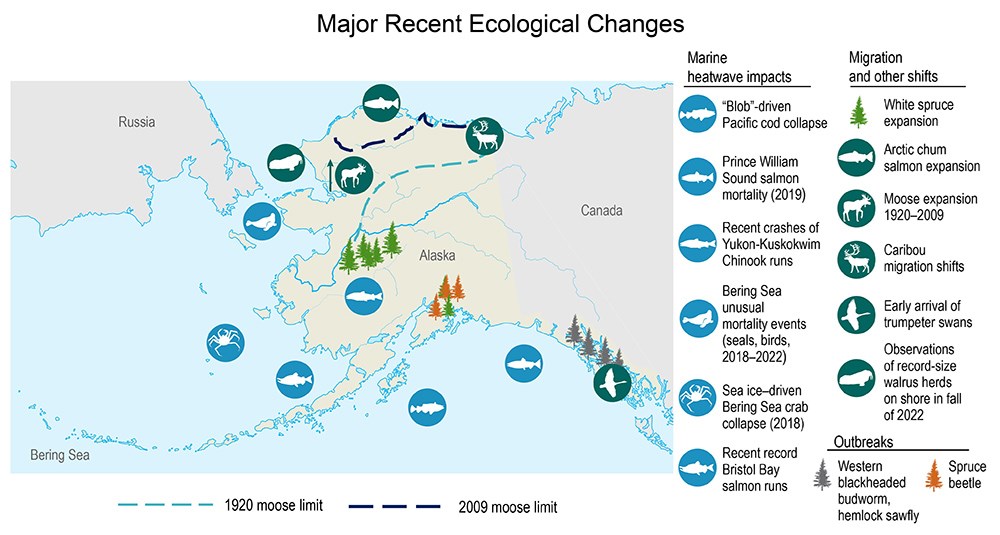

Alaska’s ecosystems are changing rapidly due to climate change. Many of the ecosystem goods and services that Alaskans rely on are expected to be diminished by further change. Careful management of Alaska’s natural resources to avoid additional stresses on fish, wildlife, and habitats can help avoid compounding effects on our ecosystems.

Alaska enjoys large, unfragmented marine and terrestrial ecosystems. This abundance makes possible hunting and fishing for subsistence use, cultural well-being, recreation, and commercial activities. At the same time, there are conflicts over land use and the allocation of hunting and fishing opportunities due to different land management regimes or distribution of harvest opportunities, with competing claims from traditional, commercial, and recreational constituencies. Climate change is expected to exacerbate existing challenges by shifting the distribution and abundance of fish and wildlife and by increasing disturbance to lands and waters. Climate-conscious management efforts can help individuals and communities adjust but cannot by themselves address the underlying changes that will continue to occur.

USGS, NOAA Fisheries, and Ocean Conservancy

Climate changes and extreme events are also contributing to terrestrial changes, affecting species distributions, habitats, resource availability, and human access . Moose and beaver are colonizing previously inhospitable Arctic areas, in part due to temperature-driven increases in shrubs, and there is evidence salmon are colonizing streams where they were previously rare or absent, presumably due to warmer waters. Ongoing warming is also associated with rapid changes in vegetation. Alaska residents are also noting unusual plants. Decreases in berry production have been noted by communities in Alaska, related to multiple climatic drivers. Exceptionally high midsummer tundra productivity (“greening”) has been observed on the North Slope of Alaska, but lower productivity (“browning”) has continued in Southwest Alaska due to drying. In 2019, the rapid expansion of a spruce beetle outbreak in the Susitna Valley (ongoing since 2016) caused extensive spruce mortality over 1.6 million acres, due in part to warmer temperatures increasing beetle development rates. In Southeast Alaska, hemlock sawfly outbreaks caused defoliation and mortality on more than 500,000 acres of forest, and a developing western blackheaded budworm outbreak is affecting Sitka spruce. Both are plausibly related to the unprecedented 2017–2019 drought in the region.

Landscape changes due to fires, permafrost, and their effects on other processes are climatically driven and increasing. Projected fire-driven transitions from conifer- to deciduous-dominated boreal forest appear to be manifesting at regional scales. Wildfires in 2019 (Southcentral Alaska) and 2022 (Southwest Alaska) burned large areas in places where fire was rare or with atypical severity, as has been seen in other parts of the western U.S. Overwintering fires, or “zombie” fires, which occur when uncharacteristically severe burning in hot, dry summers results in burning the following fire season, may also be increasing in the Arctic and Alaska. Permafrost thaw, including thermokarst (ground slumps or cave-ins) and lake drainage, is accelerating due to warming, particularly with recent wildfires and uncharacteristically warm precipitation events. These changes are projected to affect Arctic ecosystems and hydrology in important ways. Across central and northern Alaska, changes in disturbance, vegetation productivity, and permafrost will affect the region’s role in the global carbon cycle. Current evidence suggests that carbon emissions from thawing permafrost will exceed the carbon captured by increased vegetation productivity. READ MORE

Our Security Faces Greater Threats

Rapid climate-driven change in Alaska undermines many of the assumptions of predictability on which community, state, and national security are based. Further change, especially in the marine environment with loss of sea ice, will create new vulnerabilities and requirements for security from multiple perspectives and at multiple scales. Greater capacity for identifying and responding to threats has the potential to help reduce security risks in the Alaska region.

Security entails a sense of well-being and safety that is protected from or resilient to disruption. It is a combination of many interests and perspectives and reflects values such as a nation’s sovereignty and integrity or a community’s reliance on livelihoods and food sources that enable its people to thrive. Different interests are prioritized at the national/homeland, state, and community levels. Security actors at the national, state, and community level may face increasing demands for security services while also confronting the additional costs of climate change on physical infrastructure and operations, creating a double burden and making decisions even more challenging. Rising concern about climate change and increased geopolitical competition in the Arctic are reflected in recent Arctic-specific military strategy documents. In Alaska, the Department of Defense is developing new capabilities and capacities in response to these changes. READ MORE

Our Just and Prosperous Future Starts with Adaptation

Local and regional efforts are underway around Alaska to prepare for and adapt to a changing climate. The breadth of adaptation needed around the state will require substantial investment of financial resources and close coordination among agencies, including Tribal governments. The effectiveness of adaptation planning and activities can be strengthened by addressing intersecting non-climate stressors, prioritizing the needs of the communities and populations experiencing the greatest impacts, building local capacity, and connecting adaptation efforts to economic and workforce development.

In recent years, Alaska has emerged as a leader of climate adaptation initiatives in the Arctic, many of which have been implemented by regional entities and municipal, community, and Tribal governments. For many Alaskans, the ability to adapt to current and projected climate impacts is shaped by social and political factors such as food and water security, economic opportunity, and the capacity of governance systems.

Many of Alaska’s Tribes have completed or are currently engaged in efforts that increase their ability to adapt to a changing climate. These include applying for federal funding for climate resilience, conducting risk assessments, collaborating with researchers to bridge Western climate science and Indigenous Knowledge, and developing and implementing community- and regional-level adaptation plans. These activities are bolstered by the accumulated knowledge that has enabled Indigenous Peoples of Alaska and the Arctic to innovate and adapt to their changing environment for millennia. The traditional values and practices of Alaska Native cultures focus on well-being, cultural continuity, and a holistic, integrated worldview. They are often tied to components of adaptive capacity, such as environmental stewardship, communal pooling of subsistence resources, and mobility. READ MORE