Last updated: April 30, 2019

Article

Climate Corner, April 2019

Study Finds More Precipitation Volatility Likely in California

With its Mediterranean climate, California has long been susceptible to quick shifts between being very dry, and very wet. A team of researchers wondered how that would change given our changing climate. To find out, they looked at the frequencies and intensities of actual dry to wet transitions in California’s past. Using that data, they developed models that project the frequencies and intensities of similar events for the remainder of this century given different climate scenarios.

They find that the frequency of wet extremes will increase significantly, and that more intense events like none we have yet experienced this century, will also become more frequent. Their baseline for the most intense events was the ‘Great Flood of 1862,’ during which flooding in the Central Valley reached depths of up to 30 feet. Under a business-as-usual emissions scenario, they conclude that a similar event, brought about by a series of intense atmospheric rivers, is likely to occur again in the San Francisco Bay Area before 2060.

Extreme dry events are also expected to increase somewhat, even as average precipitation is expected to stay mostly the same. Overall, the authors project a 20% to 100% increase in shifts from extreme dry to extreme wet conditions, with potentially high costs to our society and our environment. Read the full study, published last year in Nature Climate Change.

How Do Precipitation Extremes Affect Salmonid Growth and Migration?

© 2019 S. J. Kelson and S. M. Carson

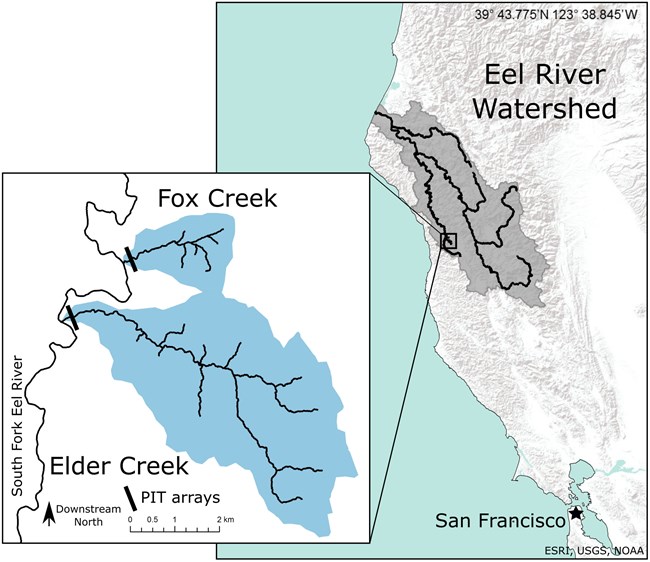

Precipitation extremes are expected to become more common in California due to climate change. A new study examines how this might affect salmonids in California’s streams. Specifically, it looks at how the recent swing from severe drought to extreme wet affected the growth and migration timing of steelhead trout in two tributaries to the South Fork Eel River in northern California. There were big differences in winter and summer streamflow during the study, between 2015 and 2018. However, to their surprise, the researchers did not find impacts on steelhead growth, health, or migration timing. Low fish growth towards the end of the summer occurred during both wet and dry years. The researchers did not look at other potential impacts to the fish, such as survival rates, in relation to streamflow. They also note that particular qualities of the South Fork Eel River, which is well shaded and fed by groundwater, may have buffered the fish against negative impacts. Such streams maintain their base flows by the end of the summer regardless of precipitation swings, and the authors suggest that they be a high conservation priority as a result. Salmonids in other types of streams that become warmer and more intermittent during the summer could be more susceptible to impacts from precipitation extremes. Check out the full paper, published in Ecosphere.