Last updated: April 20, 2018

Article

Climate Corner, March 2018

How Will Climate Change Affect National Park Bird Communities?

PLOS ONE: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0190557

This project related North American Breeding Bird Survey (summer) and Audubon Christmas Bird Count (winter) observations to climate data from the early 2000s, and projected through to 2041–2070 under high and low greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. They considered the climate tolerances for 513 bird species along with the projected climate changes across 274 national park units.

The results for each species were classified as improving, worsening, stable, potential colonization, and potential extirpation. Potential colonizations exceed extirpations in 62–100% of parks. Species turnover and potential colonization and extirpation rates were also positively correlated with latitude in the Continental U.S. Midwest and Northeast parks may see particularly high rates of change, but patterns were more extreme everywhere under the higher greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

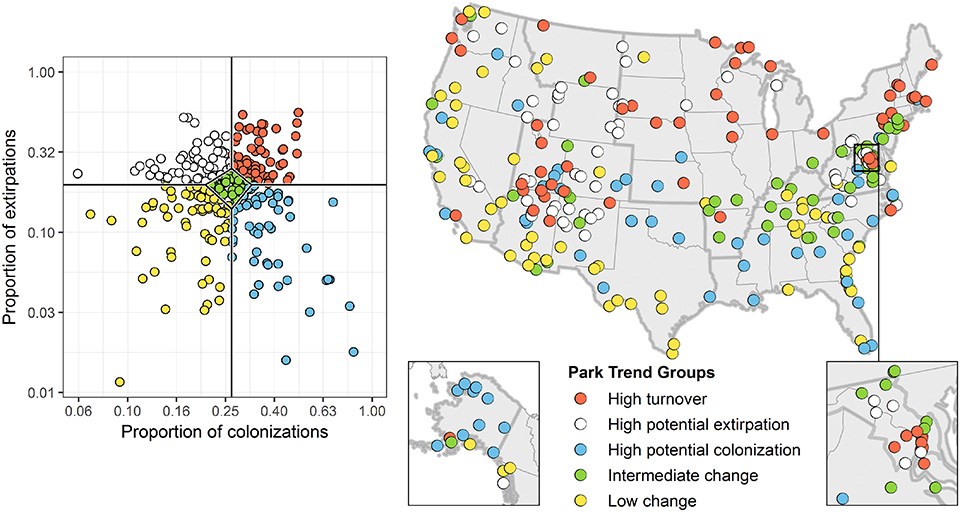

The authors used their results to classify parks into trend groups based on projected change in bird community composition (Figure 1). They also include management recommendations such as habitat restoration, maintaining natural disturbance regimes, and reducing stressors for parks that fall in the low and intermediate change groups. Parks within the high change groups however might consider ways to allow birds to respond to change such as increasing potential habitat, improving connectivity, and managing disturbance. No matter which trend group a park may fall under, climate change is challenging traditional ideas about how to preserve historical ecological conditions in parks, and may will require ways to manage in an entirely new future environments.

Read more in the PLOS ONE article, “Projected avifaunal responses to climate change across the U.S. National Park System”.

Will Tidal Wetlands Survive a Rising Pacific?

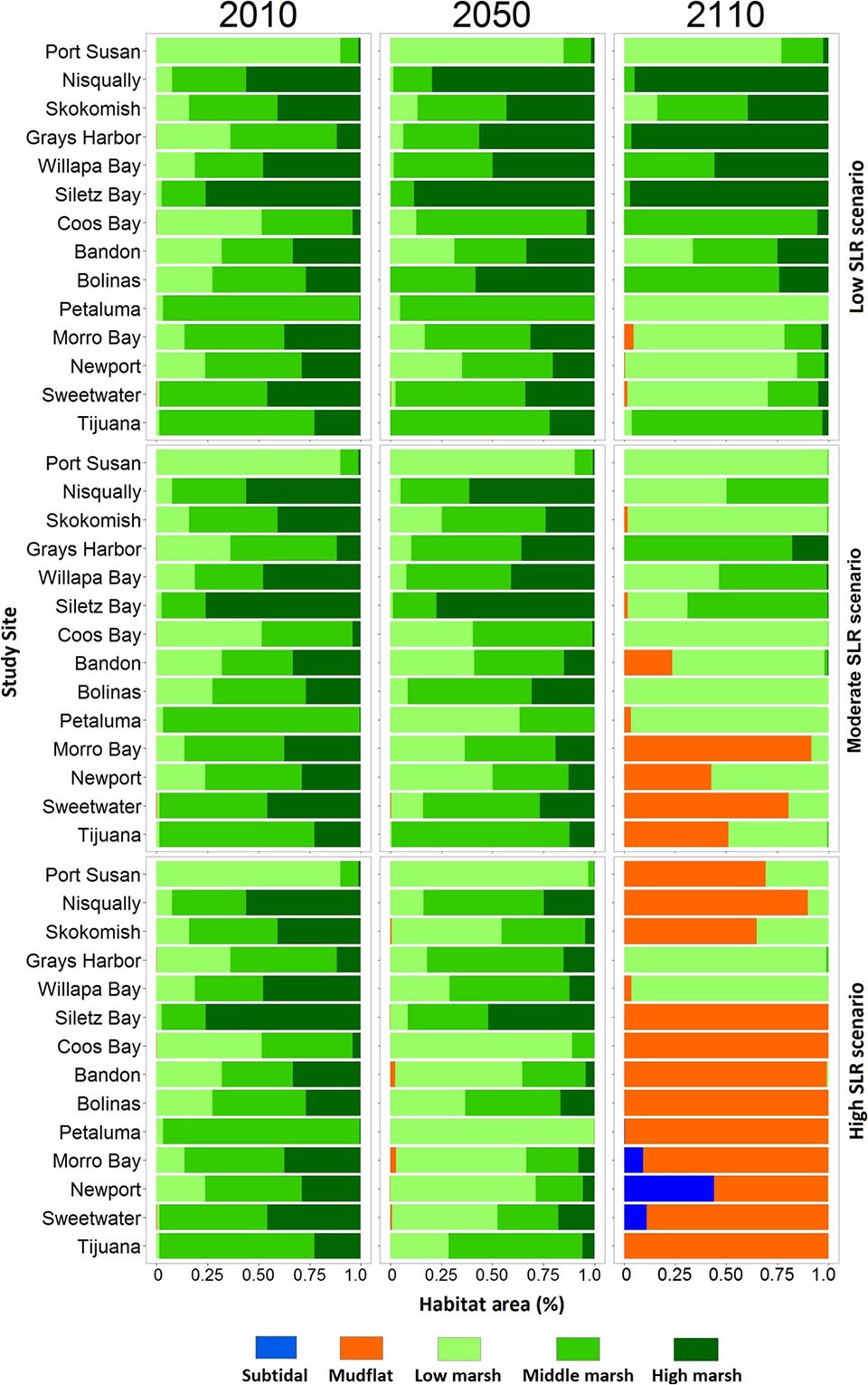

A recent study looked at vertical (sediment accretion) and horizontal (wetland migration) changes in tidal wetlands across 14 Pacific Coast estuaries under different sea-level rise (SLR) scenarios. They found that wetland migration at the California sites included in this study was constrained by adjacent human infrastructure. Given what migration potential does exist, these sites are predicted lose a total of 292 ha (59%) of marsh habitat under high SRL scenarios but 496 ha (99%) without migration.

Science Advances: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/2/eaao3270.full

The study also examined how wetland plant communities would fare under different SLR scenarios in the next 100 years. Under low SLR scenarios, habitat composition remained similar everywhere except in Southern California. Under a moderate SLR scenario however, 95% of high marsh and 60% of middle marsh areas were lost by 2110. Furthermore, high SLR scenarios showed a total loss of all high and middle marsh habitats (Figure 2). Under a high SLR scenario, 83% of marshes became unvegetated habitat (mudflat and open water) by 2110, with the greatest shifts seen in Oregon and California. Read more in the full Science Advances article “U.S. Pacific Coastal Wetland Resilience and Vulnerability to Sea-level Rise”.