Last updated: December 22, 2017

Article

The Civil War Era at Fort Vancouver

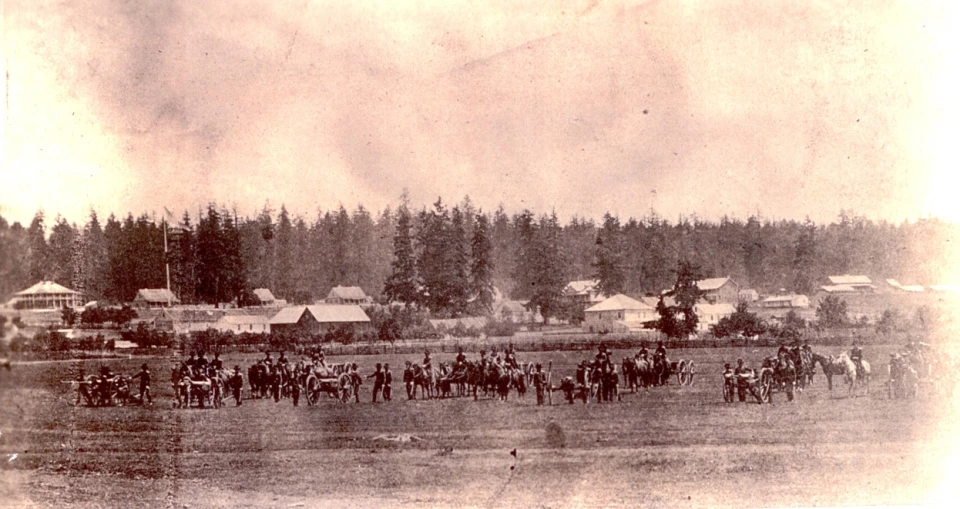

Image #1115C 89759, courtesy of the National Archives

Establishing the U.S. Army's Fort Vancouver

In 1849, the U.S. Army sited its first regional post on the ridge north of the Hudson's Bay Company's (HBC) Fort Vancouver. The Army's fort, subsequently called Columbia Barracks (1850-1853), Fort Vancouver (1853-1879), and finally Vancouver Barracks (1879-present) filled a role similar to that of the HBC's Fort Vancouver: it became the headquarters and supply base for troops, goods, equipment, and services for U.S. military posts throughout the Northwest. Fort Vancouver's soldiers protected Oregon Trail settlers, developed a transportation infrastructure, and cleared the way for settlement through negotiation, conflict, and displacement of Native people to reservations.

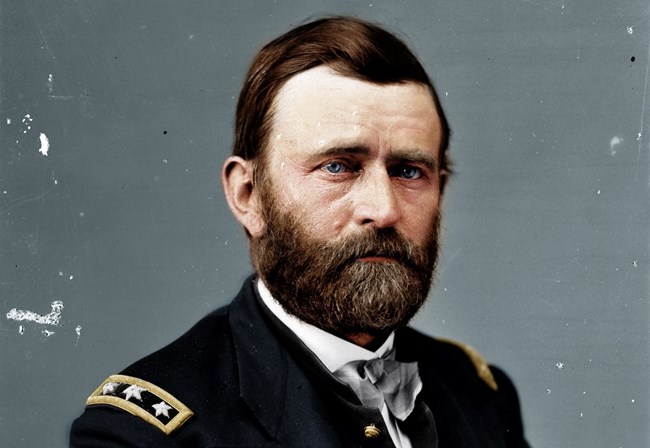

The Army's Fort Vancouver: A Military Cradle

In the 1850s, Fort Vancouver served as a training ground for many Army officers destined to lead forces in the Civil War. Most notable was Ulysses S. Grant, who came west in 1852. Although Grant resigned in 1854, when re-commissioned he became commander of Union forces, and later served as President of the United States from 1869 to 1877.Grant knew many of the notable officers who served at the fort in the 1850s later to become Union generals. The list includes Benjamin Alvord, Benjamin Bonneville, Henry C. Hodges, Rufus Ingalls, George McClellan, Augustus V. Kautz, Phil Kearney, Alfred Pleasonton, Joshua W. Sill, and George Wright. While in the Northwest, these officers developed skills that later aided them. During the Civil War, officers such as Ingalls sent coded ciphers, telegrams, and dispatches using the Northwest Chinook Jargon trade language, predating the famed World War II-era Navajo code talkers by 80 years.

Officers who served at Fort Vancouver and became Confederate generals were George B. Crittenden, William Wing Loring, Nathan Wickliffe, Gabriel J. Rains, and George Pickett, famous for his charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. Many well-known Indian foes also served in Vancouver - Phillip Sheridan, George Crook, John Gibbon, and William Selby Harney. Generals Oliver Otis Howard, Alfred Sully, and Medal of Honor recipient Nelson Miles later commanded troops from Fort Vancouver.

Neither North nor South: The Pacific Northwest in the Civil War

The national debate over slavery and states' rights influenced regional development. Many Northwestern migrants held strong political views about local control, disliked political extremism, and believed in Manifest Destiny - the providential ideal of America's extension from coast to coast.While Washington Territory (established in 1853) relied on isolation and a landscape conducive to small farms to prevent slavery and maintain neutrality, the State of Oregon (established in 1859) excluded African Americans, either "free or slave."

Conflicting opinions regarding national issues such as slavery, states' rights, and secession did not lead to open battle in the Northwest. Such conflicts manifested in threats, brawls, and sympathetic newspaper editorials on all sides, including calls for an independent republic by the Knights of the Golden Circle.

Shortly after the war, newspapers reported on a wartime plan by secessionist forces to seize the Vancouver Arsenal adjacent to Fort Vancouver, remove as many arms as possible, and blow up the powder magazine. Although not implemented, the plan demonstrates the presence of secessionist groups and the importance of the Army's presence in Vancouver.

"A Wretched Way to Serve our Lord and Country"

As the war began in May 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for the formation of volunteer army regiments from throughout the nation. At Fort Vancouver, post staffing dropped to 50, and volunteers from the First Oregon Cavalry replaced regular Army soldiers transferred to the East. The Army, which paid $16 per month in depreciating greenbacks, competed for recruits with the lure of the gold fields in California and Eastern Oregon. When the war ended in 1865, regular soldiers re-occupied Fort Vancouver.As thousands of miners, merchants, settlers, gamblers, and others headed west in the 1860s, conflict with Native groups increased. The volunteer army built Fort Lapwai and Fort Boise, determined to quell resistance from Native peoples dispossessed by increasing settlement. These soldiers also mapped thousands of square miles, identified water sources, and opened the way for further American expansion in the Northwest.

Pacific Northwest military service during the Civil War was much different than on eastern battlefields. Boredom, bad food, and removal from the heart of wartime conflict had plagued volunteers. "Oh this Garrison Life is a wretched way to serve our Lord and Country," lamented one volunteer soldier.

The families of soldiers sent to the battlefields faced periods of loneliness and homesickness. Most wives were young and inexperienced, and few were officially recognized by the Army. Many soldiers lived with or married Native women, leaving them and their children behind when assigned elsewhere. Without Army recognition, women associated with the military were considered "camp followers," a title also accorded to laundresses and prostitutes.

Northwest women also participated in the war effort. Per capita, Washington's women led every state and territory in the Union in sending supplies to soldiers.

Lincoln and the Pacific Northwest

By 1858, Abraham Lincoln had declined two positions that would have brought him to Oregon, the first as governor, the second as Secretary of Oregon, a role similar to that of a lieutenant governor. He instead nominated friend and supporter Simeon Francis as Secretary. Francis did not receive the appointment, but came to Oregon as a news editor in 1859. Francis supported Lincoln's presidency, describing him as "one of God's noble men - noble in his nature, noble in his arms - a pure and great man." Lincoln appointed Francis as Army Paymaster in Vancouver, where he served from 1861 to 1870. He died in 1872 and was buried in the post cemetery.In the days following Lincoln's April 14, 1865 assassination, Fort Vancouver mourned. Military guns fired in his honor each hour, and a 21-gun funeral salute replaced daily drill. According to an Oregon volunteer, one soldier who said that Lincoln ought to have been shot four years earlier was placed in a chokebox and sentenced to ten years' hard labor and a ball and chain.

National Park Service photo