Last updated: February 4, 2024

Article

Civilian Employees

Civilian Labor

There was a constant need for labor in Camp Nelson, especially in the Quartermaster Department. The United States Army used not only enslaved labor, but also civilian, or non-military, employees to fill this need. Hundreds of civilian employees, both Black and White, were hired in the camp.

Soon after enlistment for African American men started, in June 1864, the camp had more than 1,000 civilian employees in the Quartermaster Department alone. The department was divided into four parts:

- Transportation

- Equipage, Stores, and Construction

- Government Livestock

- General Quartermaster Duties

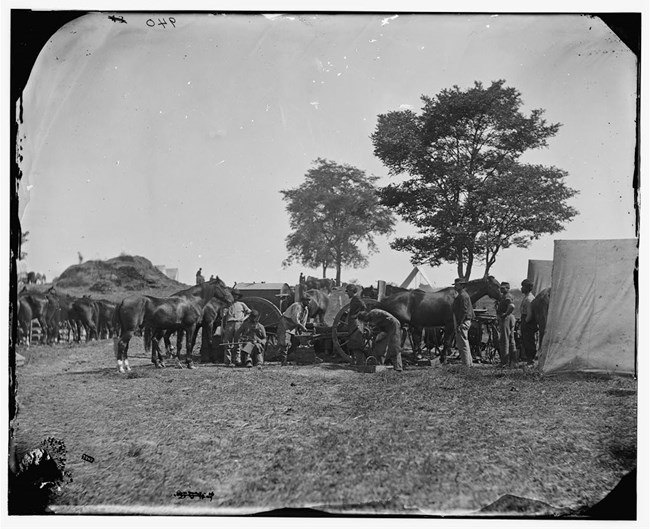

The largest of these divisions was the transportation department, with 742 employees. More than 400 of that number were teamsters, tasked with hauling supplies where needed.

Library of Congress

Skilled Labor

The civilians who came to Camp Nelson were often specially trained to do their job. For example, there were 62 blacksmiths employed in the camp. Blacksmithing required years of training to do their job well. Other skilled jobs included carpenters, stone masons, engineers, plumbers, a veterinary surgeon, and a detective.

Library of Congress

Contract Labor

Not all of the civilian employees worked inside the lines of the camp. Some of them worked in their own homes or on their farms. This was the case for people who cared for the camp's mules. Once a mule came back from campaign, they could need rehabilitation. The government's contracted employees kept the mules on their own farms, feeding them a special diet and providing good pastureage. Each animal was required to receive 9lbs. of corn per day, ample fresh water, salt and ashes in their troughs, and straw. They were regularly inspected by a detective and paid $6 per month for each animal's care.

In addition, employees caring for stock outside Camp Nelson were required to keep the animals safe. During one raid into Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan captured about 1,000 horses from Lexington, but he did not capture a single head of Government Stock because of the diligence of those caring for the animals.

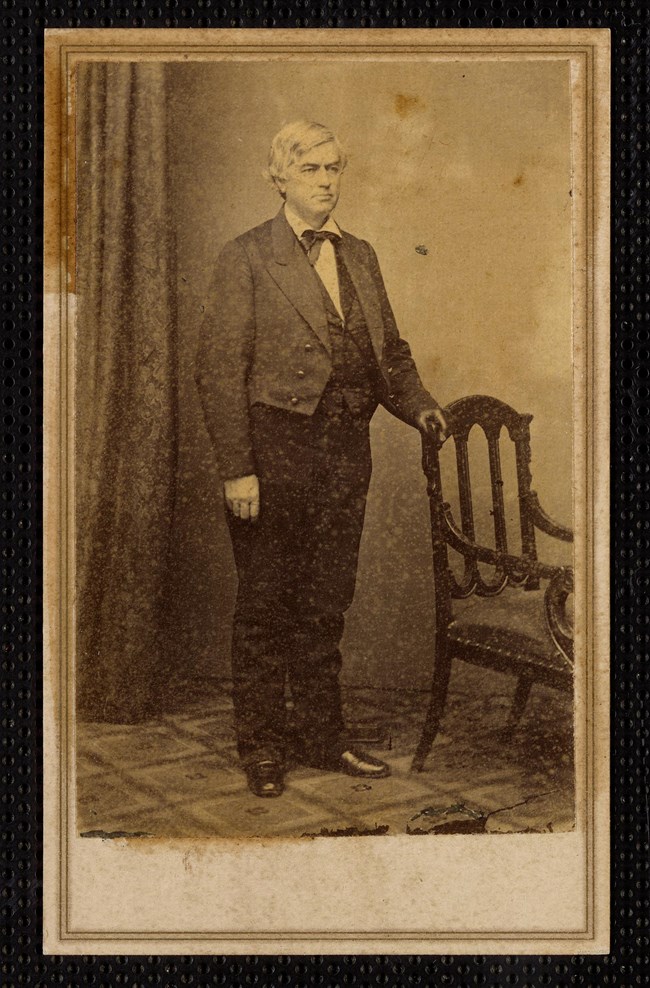

Teachers at the Refugee Home

Once the Home for Colored Refugees was established, following the Expulsion in November 1864, a school was developed for USCTs, was well as their wives and children. John G. Fee worked with Theron E. Hall to create a place for them to live and learn. Fee was unofficially in control of the school, though he advocated for a board to be make decisions for it. Working with the American Missionary Association (AMA) and the Western Freedmen's Aid Commission (WFAC), Fee secured teachers for the school.

Some of the teachers at the Refugee Home were more dedicated to the education of Black students than others. Although the White teachers were helping the Black students learn to read and write, race was an important part of their identity. They treated Black people working at the school as inferior to themselves. In one case, several of the school's white teachers refused to eat with a Black woman hired to instruct people of her own race. Eventually, ill treatment by the other teachers forced her to leave the school. These teachers did not support the idea of Black and White people being treated as equals.