Last updated: October 7, 2021

Article

Citizen Science and the National Parks: An Old Idea is New Again

NPS Photo

On Acadia National Park’s Schoodic Peninsula in Maine, children dug through rotting logs, peeling back layers and watching for sudden movements. A centipede darted from beneath the bark and was quickly caught by a young girl before it could scurry away. She dropped the wriggling creature into a bucket and held it up so her parents could see. They were among seventy participants in a BioBlitz, an inventory of plant and animal species, in Acadia National Park.

Around the country, people of all ages and backgrounds are becoming scientists. From counting centipedes to categorizing the shapes of galaxies, solving puzzles of how proteins fold, and documenting archeological specimens at historic sites, volunteers are helping to advance science in the national parks and elsewhere, doing research that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive or just impossible.

“Citizen science” may seem like a new trend, but everyday people have been expanding knowledge of the natural world for centuries, and their work has been influential in surprising ways. As we celebrate Citizen Science Day (April 13), it's a good time to reflect upon how volunteer-led science has influenced the protection of some of our most treasured places and how participants have learned and become some of our nation’s most important stewards.

For example, citizen science helped inspire the protection of Acadia National Park, the first national park in the eastern United States. In 1880, Harvard student Charles Eliot led a group of his fellow undergraduates on a summer camping expedition to Mount Desert Island in Maine. In exchange for their travel and accommodations, the young men agreed to do “some work in some branch of natural history or science.”

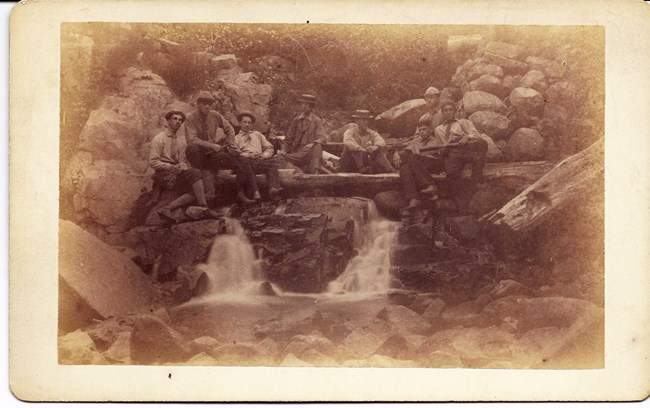

They named their new club the Champlain Society, after the French explorer who mapped the region in 1604. After sailing north from Boston and establishing camp, they began the first comprehensive natural history surveys of the area, collecting plants, birds, fish, and marine invertebrates, and recording observations of geological formations, ocean currents, and the weather. In the evenings they analyzed their specimens, played cards, and entertained the locals with their singing and fireworks displays.

Courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society

In the course of their work, this band of citizen scientists recognized the beauty of the island, its value to science, and the risk that it would be logged and cleared for the construction of summer homes and other development associated with the growing tourism economy of coastal Maine. They expressed this concern in their camp logbooks and, later, their published writings.

Champlain Society “Captain” Charles Eliot died of spinal meningitis at the young age of 37. Devastated, his father, Harvard President Charles William Eliot, reviewed his deceased son’s papers and writings about the need to protect Mount Desert Island, and his actions creating The Trustees of Public Reservations in Massachusetts, the world’s first land trust. The elder Eliot subsequently worked with his friends George Dorr and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to realize the Champlain Society’s vision. Together, with other year-round and seasonal residents, they created the second land trust in the country to protect land they then donated to the American people as Sieur de Monts National Monument (later renamed Acadia National Park) on July 8, 1916. On August 25 of that same year, the Organic Act created the National Park Service.

Today, national parks are using citizen science—past and present—to understand how landscapes are changing and how park managers might best protect the nation’s natural resources. For example, BioBlitzes in national parks around the country, like the one for centipedes and millipedes in Acadia, are helping document biodiversity and discover new species. By comparing these new volunteer observations with those of past citizen scientists who provided some of the best early records of plants and animals in parks, we can identify species that have been lost, those that are in need of special protections, and those that have newly arrived from other locations.

By participating in the scientific process in very real ways, citizens gain experience in science, especially in an era when science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) skills are highly valued. But there are other benefits: getting exercise, meeting new people, having fun, and, like the Champlain Society, being inspired by the wonder and beauty of the natural world.

In honor of Citizen Science Day, we encourage more people to continue this tradition by joining one of the hundreds of events taking place across the country. In the process, they might come up with America's next best idea.

Catherine Schmitt is a science communication specialist with Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park. Abe Miller-Rushing is the National Park Service science coordinator for Acadia National Park.