Last updated: February 28, 2025

Article

Successes of Citizen Science– Dragonfly Mercury Project

Highlights

The Dragonfly Mercury Project (DMP) is a nationwide program that engages citizen scientists in the collection of dragonfly larvae for mercury analysis. Volunteers and visitors across the country enjoy a unique experience with their national parks while contributing to nationwide research. These citizen scientists are key participants in the collection of dragonfly larvae, which serve as indicators of harmful mercury in aquatic food webs. This research helps the National Park Service (NPS) better manage risk and protect human and wildlife health against mercury pollution. The DMP engages local communities and promotes scientific curiosity while harnessing the power of citizen science to study mercury pollution nationwide. To date, the project has involved 107 parks and over 4,500 citizen scientists, contributing more than 19,000 hours of service.

- What is citizen science?

- Who are the citizen scientists in the Dragonfly Mercury Project?

- How accurate are the dragonfly data collected by citizen scientists?

- Where does the Dragonfly Mercury Project excel?

- How have we used the citizen scientist responses to facilitate an improved experience?

- Where can I get more information?

What is citizen science?

Citizen science is the involvement of the general public in scientific studies. This practice provides opportunities both to create new knowledge and to increase people’s understanding of science. In the case of public lands, citizen science programs also offer people the chance to experience and enjoy protected areas, and their natural and cultural resources, in new ways. The NPS values citizen science as an effective tool for carrying out its mission to “[preserve] unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations” and to “[cooperate] with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation..” This collaborative approach to research is a unique way to engage people in their public lands as adventurers, scientists, and stewards.

Who are the citizen scientists in the Dragonfly Mercury Project?

The Dragonfly Mercury Project is built upon the power of citizen science. Without help from hundreds of participants each year, the scope and geographic coverage of the DMP would be impossible. These citizen scientists participate in a broad range of activities from collecting dragonfly larvae to taking field notes, and even utilizing the data gathered in a classroom setting. Further, the DMP scientist team enlists a liaison within each national park or partner within the community who coordinates, trains, and leads the citizen scientists in the collection of dragonfly larvae samples from park waters. The liaison then oversees the shipment of samples on dry ice to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) laboratory, where the specimens are analyzed for mercury.

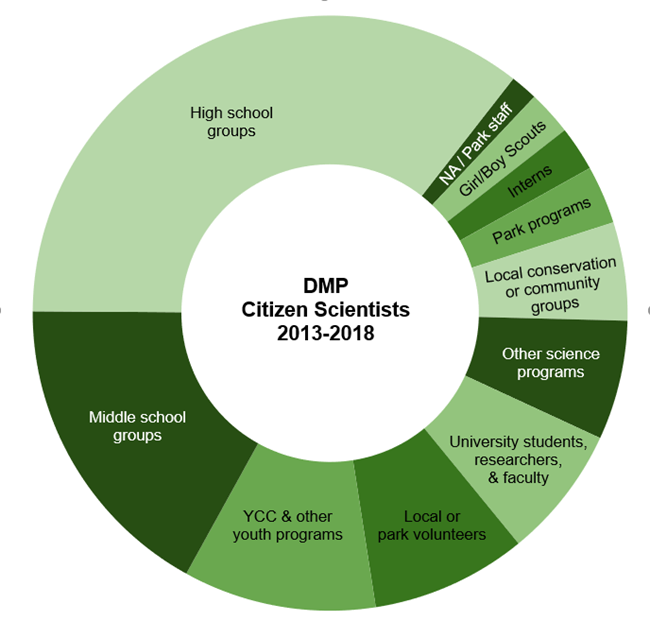

In 2013-2018, we interviewed park liaisons regarding their experiences, and synthesized results, hoping to enhance the DMP’s educational opportunities and increase data relevance among the public audience. Interview questions asked of the DMP park liaisons included (1) What was one thing that most surprised you about the project? (2) Do you have suggestions for improvement? And (3) What citizen science group participated in the sampling? The majority of citizen scientist participants were lumped into three main categories based on the interview results: high school groups (35 percent), middle school groups (17 percent), and the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) and other youth programs (11 percent) (Figure 1). Interview results indicate that nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of the DMP participants are youth.

How accurate are the data collected by citizen scientists?

The Dragonfly Mercury Project gives participants the opportunity to hone their scientific skills and precision not only by sample collection, but also by the identification of dragonfly larvae to 1 of 6 families in Odonata: Anisoptera and through the measurement of larval length. The sampling kit provided to the park liaison ahead of scheduled sampling events contains a sampling guide and additional resources to help identify and measure dragonfly larvae. These records are then validated in the USGS lab. While citizen science programs managed by a high quality, centralized laboratory, like the DMP, can be very successful in producing large amounts of accurate scientific data, several NPS units and citizen scientists still wanted to know: How accurate are our data before validation? Typically, the identification of macroinvertebrate larvae to family is the work of trained taxonomists!

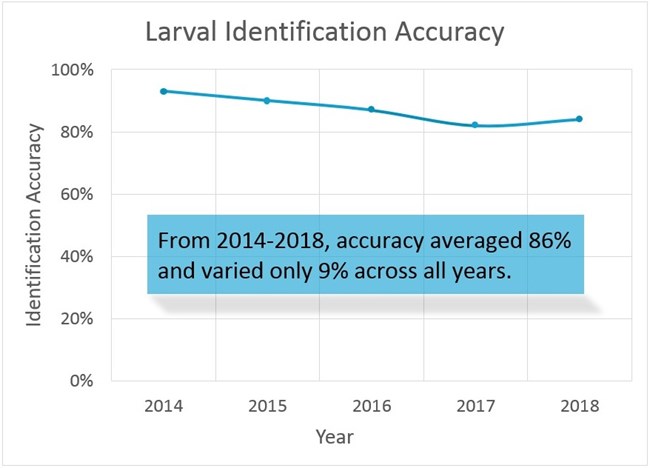

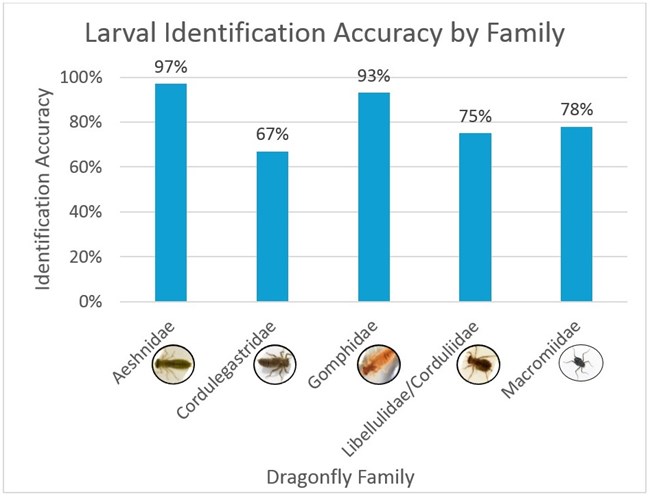

Well, the dragonfly larvae identification accuracy rates are actually quite good! An average of 86 percent of the dragonfly larvae were correctly identified to family by the citizen scientists participating from 2014-2018 (Figure 2). The larval identification accuracy rates reveal how well some Anisoptera families are correctly identified compared to other Anisoptera families. Dragonfly larvae from the family Aeshnidae (Darners) are most easily recognized by the citizen scientists and have the highest accuracy rate (97 percent). DMP citizen scientists also most frequently encounter Aeshnidae, as compared to other families (Figure 3). On the contrary, the family Cordulegastridae (Spiketails) have the lowest accuracy rate (67 percent). Interestingly, Cordulegastridae larvae are often misidentified as Aeshnidae, likely because both families have fusiform (i.e., “cigar shaped”) bodies (Figure 4). The family with the second lowest accuracy rate, Libellulidae (Skimmers)/Corduliidae (Emeralds), are often misidentified as Macromiidae (Cruisers) (Figure 5). In this instance, both families have stout and robust bodies. (Libellulidae and Corduliidae are lumped together as one family because the larvae from each family cannot be reliably distinguished in the lab.)

Metadata for these graphs can be found at the bottom of this page.

Tips for Improving upon Dragonfly Identification Accuracy Rates

Left image

Ventral view of dragonfly larvae

Right image

Lateral view of dragonfly larvae

Left image

Ventral view of dragonfly larvae

Right image

Lateral view of dragonfly larvae

Where does the Dragonfly Mercury Project excel?

Entering its 10th season of sampling, the DMP’s continued success has come not only from the allure of dragonflies, but also from the recognition of the different goals for the engagement of citizen scientists, and careful consideration about which aspects of planning, implementation, and interpretation are best suited to undertake the study. Participating parks receive a post-sampling survey to address what went well and to suggest areas for improvement. A strong majority of the 107 NPS participating units to date elected to engage in the project multiple years (Figure 6), commonly citing “getting kids outdoors” as a highlight, alongside:- The extraordinary levels of enthusiasm and curiosity exhibited by participants!

- The shocking ease at which dragonfly larvae samples are located!

- The adept and fascinating life cycle of dragonflies!

- The well-designed and streamlined structure of the project!

Project testimonials including “Anyone can pick it up and pull it off!” underscore how citizen scientists interact with the Dragonfly Mercury Project and highlight the project’s ability to attract the public in accordance with the goals for engagement:

1. Providing Biodiversity Discovery

- "Fascinated by the dragonfly life cycle"

- "Addicting to look for larvae"

- "...thrilled to see the biological aspects of the park, as they are usually more constrained to the historical part of it"

- Found plants not seen before

2. Connecting People to Parks

-

"One of the best teaching days of my life."

-

"Looking at parks as a different kind of classroom"

-

"Connected with the local school in a meaningful way"

-

"Students were inner-city youth and had never done anything like this"

3. Fostering Education & Outreach Opportunities

-

"It's not just a learning experience; it empowers"

-

"Glad to see citizen science growing and addressing wide-scale issues."

-

When the data was released back to a biology class, "a huge light came on... students were beaming with pride."

-

"Good for community as a whole"

Park liaisons noted that the high school students truly enjoyed and were interested in the project. Intern groups reported viewing this field-based project as a reward and reprieve from indoor work. For other youth groups, the project helped identify interests and a career path. Moreover, park liaisons who led local community groups revealed that the project achieved both internal and external communication that otherwise would not have occurred. For example, many parks linked with local experts to assist with fieldwork and identification, and park staff learned from others within the park who had specific expertise in fields like entomology, for instance.

Based on interview responses, the DMP team identified three core tenets on the value of participation: (1) interpreting and utilizing the data; (2) identification of dragonfly larvae; and (3) promoting scientific literacy.

How have we utilized the citizen scientist responses to facilitate an improved experience?

The interviews inform the Dragonfly Mercury Project on many areas that could be improved upon. We learned that the facilitation of a community of practice for teachers and emphasis on existing data literacy and curriculum resources would greatly benefit the high school teacher and student group. For interns and youth groups, the DMP should create a plan for workforce development and better link career paths with these participants. We were largely unaware how many local community groups exist, and therefore we need to continue facilitating connections with such groups.

Inquiries with the park liaisons allow the DMP to better connect with the citizen scientists who make this work possible, and to ultimately create a better product for our varying audiences. From 2013-2018, strides have been made to address and focus on these values and make the DMP a truly collaborative project between scientists, parks, and the public participants. Each year, the DMP uses the feedback garnered from the interviews to refine sampling guidance, improve existing educational tools, and build new project partnerships.

For example, based on the values identified by the respondents, the following advancements and products were circulated over the past couple years in an attempt to better streamline and improve the project.

|

Core Tenet |

Product |

|---|---|

|

Faster data fact sheet turnaround to parks |

|

Updated sampling guide (2018) with new larvae images |

|

In development: educational curriculum and exercises |

Further, a Dragonfly Mercury Project Steering Committee Workshop held in August 2019 at Rocky Mountain National Park yielded the following needs and future products that would increase program relevancy for citizen scientists and other DMP audiences: field coordinator, to allow DMP program manager to grow value and impact of the project; educational coordinator, to better engage DMP citizen scientists and the public; communications specialist, to improve understanding of mercury issues; research support, to develop tools and options for mitigating risk from mercury; postdoctoral researchers, to develop a quantitative model to forecast risk from mercury, and to test the efficacy of dragonfly larvae as indicators of mercury emission reductions.

Where can I get more information?

Email us with any questions!