Last updated: March 8, 2018

Article

African American Participation in the Civil War Campaign For Chattanooga

The Civil War Campaign for Chattanooga saw more than 150,000 men clash throughout the late summer and fall of 1863 over control of the city of Chattanooga, which was a vital rail hub. However, far more than just soldliers served on the battlefields of Chickamauga and Chattanooga. Hundreds, and possibly thousands, of African Americans worked for the armies, and, at time, found themselves in harm's way.

As it moved south, the Union Army encountered large numbers of enslaved people. Sometimes, the army would emancipate some of the men and hire them as teamsters, wagon drivers, or even servants to officers. For example, Peter Dabney was liberated by the 15th Wisconsin Infantry during the fight for Island No. 10 in western Tennessee. He was then hired to attend to an officer in the regiment, an occupation he remained in through the Battle of Chickamauga. He later served in the United States Colored Troops and fought at the Battle of Nashville. After the war, he moved to Wisconsin - home state of the men who liberated him - where he became active in the Grand Army of the Republic and even held elected office for a short while in his community.

NPS Photo

John McCline was ten years old in 1862, and was enslaved by a Dr. James and Mary Hoggatt, at a plantation near Nashville called “The Clover Bottoms.” When the Union Army of the Cumberland marched by, a soldier in the 13th Michigan Infantry named Francis Murray, saw young John sitting on his mule, Nell, by the side of the road and called out “Come on Johnny, and go with us up North, and we will set you free.” These words set in motion a chain of events that would lead ten year old John McCline from enslavement to the battlefield. As Union soldiers from the 13th Michigan Infantry marched by around the time of the Battle of Stones River, they offered to take “Johnny” out of slavery and into the army. Over the next few months he tended the mules for Company C, 13th Michigan Infantry. In mid-September 1863, McCline, along with hundreds of other African American teamsters and laborers with the Union Army, was in Chattanooga, watching soldiers stream southward. He recalled:

“The battle began while we were eating breakfast, cannon roared, smoke from the awful fighting field, could be seen rising slowly in the distance. In the afternoon slightly wounded soldiers, heads bandaged, arms in slings began straggling into town…All reported that our forces were greatly outnumbered and that a setback was probable. The glaring facts were apparent when, late in the evening, the entire force was driven from the field, sustaining heavy losses, and were practically shut up in the town. Our regiment…suffered heavily…Francis Murray (we called him Frank) of my Company, received terrible wounds from which he died on September 21st. He was the handsome young soldier who, nine months before, said to me as I sat there on old Nells fat back: ‘Come on Johnny, and go with us up North, and we will set you free.” John McCline's narrative was published as Slavery in the Clover Bottoms (University of Tennessee Press, 1998).

Sometimes these formerly enslaved men found themselves as active combatants. As Thomas Coles described to an interviewer from the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, he had helped load and fire cannon at the Battle of Chickamauga, probably along Dyer Ridge during the Confederate Breakthrough of September 20. In a twist of fate, Robert Coles, whose family had enslaved Thomas, was marching across the field towards Thomas at that very moment. Nearby, Jack Hines, who had been enslaved in Kentucky before the war, was with the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry when he was severely wounded and nearly captured during the Union retreat from Chickamauga.

Library of Congress

While most of the black men accompanying the Union Army had some sembelance of choice in the matter - the same could not be said of those with the Confederate Army. Confederate Army regulations permitted men to take an enslaved man into the ranks with them to serve as a "body servant." The body servant's job would be to attend to the needs of the soldier. They cooked, carried supplies, and carried out a variety of other tasks around the camp to help ease the burdens of soldiering for their enslaver. During battle, they would stay with the wagons, carry supplies to the front, and assist with evacuating the wounded. At times, this put them in harms way, and in rare instances might even take up arms in the heat of battle. For example, one soldier in the 4th Tennessee Cavalry recalled that during their fight around Reed's Bridge at Chickamauga, some 40 of their enslaved servants had picked up weapons to help beat back a Union force. It is difficult to know exactly how many men were enslaved in Confederate Army of Tennessee in the fall of 1863. One brigade reported "that there were an average of one hundred and ten negroes belonging to the officers in this Brigade..." just before the Battle of Chickamauga.

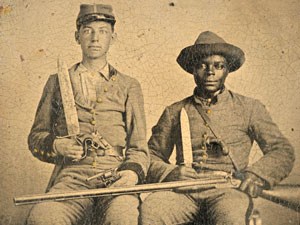

The most famous of the Confederate body servants at Chickamauga was Silas Chandler. Silas was enslaved in the 44th Mississippi Infantry as a servant to Andrew Chandler. Andrew was severely wounded at Chickamauga, and Silas took him home to Mississippi. The Chandlers received a good deal of notoriety years later as a result of a photograph that depicted Silas and Andrew both brandishing weapons and in Confederate uniform. Despite the appearances, Silas, nor any of the other black men with the Confederate Army at Chickamauga, were considered to be soldiers by the Confederate Army. When they entered the battlefield here, many of these men faced a choice. They could run to the Union army as free men - and some of them did. But if they did so, they faced the prospect of never seeing their family again. Many, including Silas Chandler, opted to not go free here at Chickamauga, and instead remained with their soldier.

These are just a few of the men who experienced the horror of battle at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga. Regardless of which army they were with, those that survived got to experience the one thing none of them ever imagined that they would - freedom. As a result of the Civil War, four million people were set free, and the passage of Constitutional Amendments began the process of extending the rights and priveleges of citizenship to all Americans.