Last updated: November 13, 2019

Article

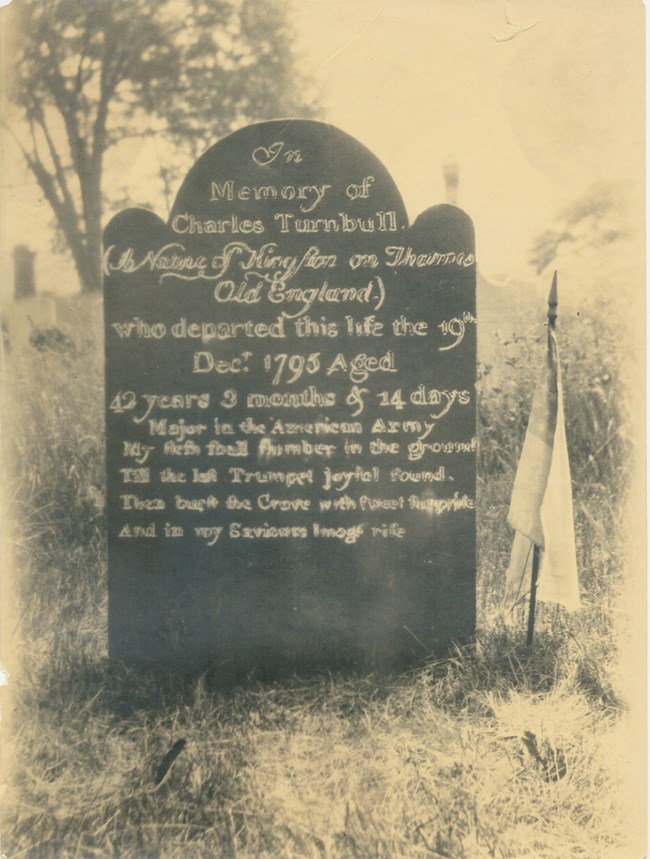

Charles Turnbull: Continental Army artillery officer buried at St. Paul's

National Park Service photo

Prisoner of war, on parole, for threee years

during Revoltuionary War

September 2019

The life and military experience of Charles Turnbull, who served in the American army’s artillery corps during the Revolutionary War, illuminates several interesting aspects of the War for Independence, particularly the ordeal of officers captured by the British. Turnbull, who died in 1795, is buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site.

Turnbull’s experience also reflects a pattern of recent arrivals from England joining the Patriot cause. Born in Kington-on-Thames (Old England, as referenced on his gravestone) in 1753, he reached the shores of America, settling in Pennsylvania, in 1774 or 1775, on the eve of the American Revolution. He emigrated without his parents, part of the large influx of British subjects who left the home country for various reasons of discontent and almost immediately joined the rebellion. Thomas Paine also reached Philadelphia from England in 1774, and wrote “Common Sense,” one of the period’s great political pamphlets.

While no documentation records Turnbull’s reasons for enlisting in the patriot cause, it is revealing that he enrolled in the artillery. This branch of the army was regarded as the elite troops of the day, mostly because the corps needed soldiers capable of using geometric and mathematical calculations necessary to effectively locate canon and accurately deliver the balls to inflict maximum damage on the enemy. Turnbull enrolled in Procter’s artillery, formed in Philadelphia in April 1775, probably motivated by the galvanizing news that spread across the colonies about the outbreak of fighting at Lexington-Concord in Massachusetts. Promotion was rapid, reflecting his abilities as a soldier and the fluid nature of a newly formed military unit. He reached sergeant by November, and about a year later, in October 1776, Trumbull was listed as a second lieutenant in Proctor’s battalion.

There is a minor scar in his military record, from January 1777. Lieutenant Turnbull, along with other officers in the artillery regiment, was charged with a complaint of an unspecified nature by three other members of the unit, including two sergeants. There was no disciplinary action, which likely meant the allegations originated in a personal dispute.

The young officer was captured at the Battle of Bound Brook, New Jersey, on April 13, 1777. This was one of the actions in advance of the major movements of the campaigns of 1777, which eventually led to British capture of Philadelphia. At Bound Brook, a combined British and Hessian (German auxiliaries) force of about 4,000 under General Charles Cornwallis launched a surprise attack on a Continental Army outpost in northern New Jersey led by General Benjamin Lincoln, with the goal of capturing the entire American force. General Lincoln and much of his army escaped, but Lieutenant Turnbull was one of a reported 22 troops from the artillery regiment, out of 70 total, captured by the Crown forces.

That surrender began Trumbull’s three year experience as a paroled officer, in a twilight zone of sorts. Officers rarely faced the grim prospect of prison ships. These were floating detention sites, large British vessels moored around New York, especially in the East River, where thousands of American soldiers died of starvation and disease. Instead, officers were paroled, or allowed to live on their own in a designated area, under honor as a gentleman to refrain from re-joining the war until exchanged for a prisoner of similar rank. In the 18th century, warring parties often had general agreements, or cartels, on a regular exchange of prisoners. But the nature of the Revolutionary War complicated this tradition. The British were reluctant to engage in a general agreement on exchanges, fearing such an arrangement implied the tacit recognition of the legitimacy of the United States, while the English regarded the Americans as rebels or traitors. Instead, there were sporadic exchanges of prisoners, following often testy and difficult negotiations between officers of the two sides. Alexander Hamilton, for instance, represented General Washington and the Continental Army at several such meetings.

Beyond British reluctance to appear to acknowledge the legitimacy of the United States, American intransigence on issues of funds and number of prisoners, and other conditions, delayed these transactions. On April 3, 1780, following delays for all of these reasons, an agreement on exchanges was concluded which included Turnbull. The officer was allowed to rejoin his artillery regiment, promoted to captain during his period of parole. During those three years awaiting exchange, Turnbull was allowed to live more or less on his own, in the Flatbush section of Kings County, part of the modern borough of Brooklyn in New York City. That part of New York was firmly under British control throughout the war. An allowance, theoretically funded through the American government, covered living expenses -- meals and lodgings. During that period of limbo, Turnbull met his future wife Phebe Bloom, who lived in Kings County, a descendant of one of the early Dutch settlers of New Netherland. They were married in February 1781, and Phoebe bore four children who survived infancy.

The regiment Charles rejoined had been re-constituted as the 4th Continental Artillery, and it was engaged at the decisive Battle of Yorktown, in Virginia, in October 1781, with Captain Turnbull likely present. Part of the 4th Artillery joined General Nathaniel Greene’s army in the Carolinas after the British surrender at Yorktown, and Turnbull may have been detached for service there. He was discharged as part of the final release of the Continental Army in June 1783. Turnbull had returned to New York by late November 1783, when the final British troops left the city, signaling the end of the War for Independence. We learn something about the pride and satisfaction over the triumph of the revolution expressed by an American officer -- who had lived in England on the eve of hostilities -- through this description of the evacuation:

"The British army is at last left us they passed the narrows last Saturday, and lucky for us General Washington) got possession of New York as he did, for a packet arrived three days after, ordering (British commanding General Sir Guy) Carlton that if it was not convenient to leave the city to keep her possession untill spring. My dear fellow it would have revived all your military virtue to have seen the British retreat and give up the post to our advance guard, the troops made a beautiful appearance, the officer who commanded the battery made his soldiers grease the flag staff and unweave the Heallyards (halyards) which put our troops to some difficulty before they could hoist the thirteen stripes which flew in triumph to the great mortification of our enemies. The fireworks which was at west point, was exhibited last Tuesday evening at the bowling green in this city they excelled anything I had ever seen and allowed by many good judges to exceed anything they ever seen."

Turnbull’s wartime experience greatly influenced his civilian life in the years after the conclusion of hostilities -- foremost in civilian residence. He returned to Kings County, with his wife, where they developed a home and raised their children. Turnbull established a large farm of 150 acres in Bedford, and joined the grain producing economy of Kings County. Cultivating such a large tract of land would have required a large labor force, and here Turnbull would seem to be out of synchrony with the ideals of the American Revolution. The former Continental Army officer was a slave-owner, an indication that he shared the inability of many wealthy New Yorkers to comprehend the discrepancy between supporting the cause of republican government and owing enslaved Africans. In 1790, he owned seven enslaved people, who doubtless helped cultivate the plants and maintain the infrastructure on his large farm. At his death five years later, Turnbull owned two enslaved people. It is difficult to know if this reduction was a caused by a conscious policy of emancipation, or was the result of other developments. New York did not adopt gradual emancipation until 1799.

Brooklyn farms like Turnbull's harvested wheat, rye, oats, barley corn and other grains serving the rapidly growing markets of New York City. Produce was usually transported by horse-drawn wagons to the area of today’s Brooklyn Heights, then the small City of Brooklyn, before the farm products were ferried across the East River to the nation’s largest city. By most measures, this was a prosperous and satisfying time for Turnbull, who enjoyed the fruits of independence which he had helped achieve. In 1787 he wrote to his brother who still lived in England: "When I reflect on the many hours I idly spent when in London and the real happiness I now enjoy with my little family around me [it] makes me regret that I did not dedicate them in a more agreeable manner. I would not change my situation I assure you...to become his high Mightiness George prince of Wales."

His public and professional life were also formed by his military service. Perhaps most importantly, cementing his wartime comradeship and alliances, Captain Turnbull -- who received the brevet rank of Major, which is on his gravestone -- enlisted as a charter member of the Society of the Cincinnatus. This prestigious, exclusive society of officers of the Revolution was founded in 1783. Through this membership, Turnbull developed associations with other veteran officers who were prominent leaders in public life. These included George Clinton, the Governor of New York and one of the leading military and political figures of the Revolution. Governor Clinton, another original member of the Society of the Cincinnatus, appointed Turnbull as Inspector General of the New York Militia with the rank of Major. In addition, the former artillery officer was selected by the state’s chief executive for the post of Sherriff of Kings County for a two year term of 1789 to 1791. Influential figures, county sheriffs were the highest law enforcement officials in their jurisdictions, and duties included supervising elections and tax collection, overseeing jails, arrests, and serving warrants. Compensation was modest, but Turnbull reported that “an office not so lucrative, but may be, if I fill with Fidelity, a prelude to something else.”

Charles and Phebe enjoyed the triumphs of the American Revolution, but also experienced the tragedies of the 18th century, when public health and medical care followed traditional, pre-scientific methods. Phebe died in 1791 through complications of pregnancy, “carried off by a violent flooding,” Charles reported sadly to a nephew. This brief description probably meant Phebe died from heavy bleeding and amniotic fluid embolism, which caused the most deaths during delivery. Shortly after Phebe’s death, Turnbull married a woman named Mary Lefferts, when re-marriage after the passing away of a spouse was common. The sheriff sold the Bedford home and moved to Eastchester, in Westchester County, the parish of St. Paul’s Church, perhaps 20 miles away. It is likely he attended services at the stone church, an Episcopal Parish and the only house of worship in the vicinity.

Turnbull died in 1795, aged only 42. Although no surviving records list a cause of death, even in the 18th century, that represents an early death for a man of wealth, indicating a fatal disease of some kind. Burial followed in the St. Paul’s cemetery. His final resting place is marked by an impressive, tri-partite sandstone marker noting his age, military service, and recording the last phrase of “Lord I am Thine,” a popular 18th century hymn.