Article

Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Many Americans first entered the worlds of information and imagination offered by reading when they walked through the front doors of a Carnegie library. One of 19th-century industrialist Andrew Carnegie’s many philanthropies, these libraries entertained and educated millions. Between 1886 and 1919, Carnegie’s donations of more than $40 million paid for 1,679 new library buildings in communities large and small across America. Many still serve as civic centers, continuing in their original roles or fulfilling new ones as museums, offices, or restaurants.

The patron of these libraries stands out in the history of philanthropy. Carnegie was exceptional in part because of the scale of his contributions. He gave away $350 million, nearly 90 percent of the fortune he accumulated through the railroad and steel industries. Carnegie was also unusual because he supported such a variety of charities. His philanthropies included a Simplified Spelling Board, a fund that built 7,000 church organs, the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Carnegie also stood out because some questioned his motivations for constructing libraries and criticized the methods he used to make the fortune that supported his gifts.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the "Medford Free Public Library," the "Carnegie Free Library," the "Carnegie Libraries of Washington Thematic Resource," "Carnegie Library Thematic Resource - Utah," and other sources related to Andrew Carnegie and his libraries. It was written by Roberta Copp, an Information Services Librarian at Richland County Public Library, South Carolina. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on American social history between 1865 and 1919, particularly the widespread efforts of reform. Students will better understand the role of philanthropy in U.S. history and the place of libraries in American culture.

Time period: Late 19th century to early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright" relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the connections among industrialization, the advent of the modern corporation, and material well-being.

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the rapid growth of cities and how urban life changed.

-

Standard 2C- The student understands how new cultural movements at different social levels affected American life.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright" relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard C - The student explains how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

- Standard G - The Students describe how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

- Standard A -The student examines persistent issues involving the rights, roles, and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard F - The student explains and illustrates how values and beliefs influence different economic decisions.

Find your state's social studies and history standards for grades Pre-K-12

Objectives for students

- To understand how Andrew Carnegie epitomized the American dream of "rags to riches."

- To explain why Carnegie chose libraries to be among his first and foremost benefactions.

- To examine the impact of libraries in America and how they reflect the values of the society they serve.

- To explain the effects of philanthropy on the United States.

- To determine how their own community libraries are being supported and how they were supported in the past.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

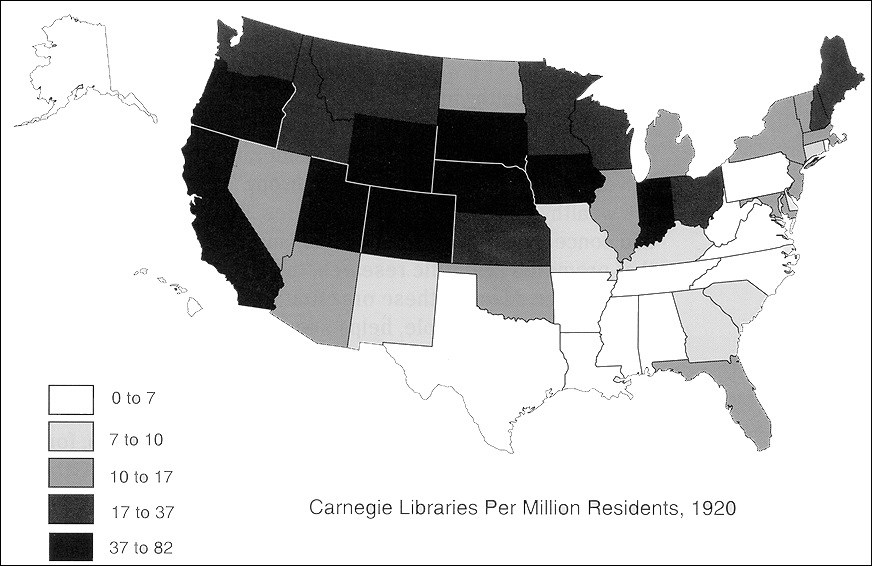

- One map showing the distribution of Carnegie libraries in the United States in 1920;

- Three readings examining Andrew Carnegie, how communities were able to obtain a Carnegie library, and a history of two such libraries;

- One document demonstrating the application procedure for a Carnegie library;

- One table demonstrating the distribution of Carnegie libraries in the United States;

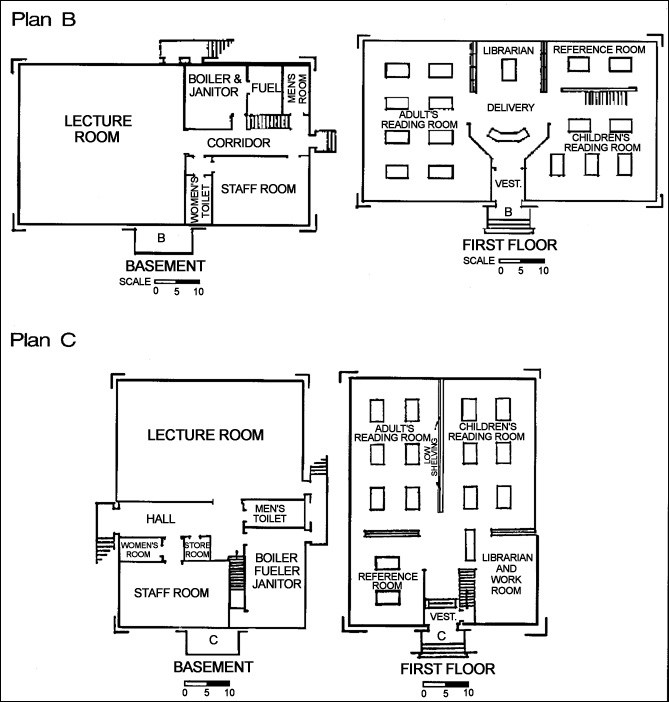

- One drawing of a sample building plan for a library;

-

Five photographs of Carnegie Libraries in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Washington, Utah, and Kansas;

-

One illustration by Harper's Weekly of Andrew Carnegie building his legacy.

Visiting the site

Although Carnegie libraries are widespread, it may not be feasible for your students to visit one. Through their research, they should locate the nearest Carnegie library. Encourage visitation if possible, but photographs and floor plans may have to suffice.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

1. What point might this cartoon be making?

2. What do the buildings in the picture have in common?

Setting the Stage

Libraries arrived on the North American continent with the first European settlers. Religious books, primarily for the use of the clergy, formed the center of most 17th-century collections. The richest colonial merchants and planters often developed their own libraries, but the number of people regularly reading books, other than the Bible, was quite small.

Books became available to a broader public as the 18th century progressed. Improvements in printing methods lowered their cost, making them affordable to more people. Increased interest in commerce, science, and art spurred a demand for more information--a demand that was often best satisfied through reading. Colonists began to form social libraries in which individuals contributed money to purchase books. Library societies sprang up in urban centers; outstanding examples include those still existing in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Charleston, South Carolina, and New York, New York. However, such societies generally only lent their books to those who had donated money.

Libraries continued to develop after the Revolutionary War. Women, for example, created their own collections, with books often circulating great distances among farms and plantations. Between 1815 and 1850, library societies increasingly concentrated on specialized subjects. Mercantile libraries held books of interest to clerks and businessmen, while the collections of mechanics’ and seamen’s libraries specialized in their particular trades. These libraries were supported by business owners and provided educational and social opportunities for young men.

During the second half of the 19th century the "free" library movement--that is, open to the public at no charge--began to spread. Reformers saw libraries as a valuable tool in their attempts to repair what they saw as the flaws in a rapidly industrializing nation. More directly, libraries provided information about an increasingly complicated and technical world. Reformers believed libraries could teach millions of immigrants how to succeed in America, and provide the poor with the knowledge they needed to rise in society. Also, reformers thought well-educated voters would be better able to resist the lure of dishonest politicians. Finally, libraries offered an alternative to unwholesome pursuits such as drinking and gambling.

Making libraries a tool for reform, however, proved difficult. Lack of money, insufficient book collections, and limited memberships prevented social libraries from expanding as fast as the American population. America’s rapidly growing towns and cities demanded many services, such as better transportation, sanitation, and schools. Buying books and building libraries were, for most citizens, a lower priority.

Even though a relatively small number of places had developed public libraries before the 1880s, enough progress had occurred to give supporters hope. Cities gradually gained the right to tax, which held the potential to supply funds. The growth in public schools indicated an increasing interest in education. It was at this point that the generosity of Andrew Carnegie accelerated the development of American libraries. His donations provided communities across the country with millions of dollars to build new libraries.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Carnegie libraries in the United States, 1920.

Questions for Map 1

1. Why might the figure "per million" be more valuable than the absolute number of libraries when explaining the impact of Carnegie's contributions?

2. Which of the five categories does your state fall into?

3. Which region of the country has the highest per million figures? Which region has the lowest? What might be the explanation for this trend?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie’s decision to support library construction developed out of his own experience. Born in 1835, he spent his first 12 years in the coastal town of Dunfermline, Scotland. There he listened to men read aloud and discuss books borrowed from the Tradesmen’s Subscription Library that his father, a weaver, had helped create. Carnegie began his formal education at age eight, but had to stop after only three years. The rapid industrialization of the textile trade forced small businessmen like Carnegie’s father out of business. As a result, the family sold their belongings and immigrated to Allegheny, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Although these new circumstances required the young Carnegie to go to work, his learning did not end. After a year in a textile factory, he became a messenger boy for the local telegraph company. Some of his fellow messengers introduced him to Col. James Anderson of Allegheny, who every Saturday opened his personal library to any young worker who wished to borrow a book. Carnegie later said the colonel opened the windows through which the light of knowledge streamed. In 1853, when the colonel’s representatives tried to restrict the library’s use, Carnegie wrote a letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch defending the right of all working boys to enjoy the pleasures of the library. More important, he resolved that, should he ever be wealthy, he would make similar opportunities available to other poor workers.

Over the next half-century Carnegie accumulated the fortune that would enable him to fulfill that pledge. During his years as a messenger, Carnegie had taught himself the art of telegraphy. This skill helped him make contacts with the Pennsylvania Railroad, where he went to work at age 18. During his 12-year railroad association he rose quickly, ultimately becoming superintendent of the Pennsylvania’s Pittsburgh division. He simultaneously invested in a number of other businesses, including railroad locomotives, oil, and iron and steel. In 1865, Carnegie left the railroad to manage the Keystone Bridge Company, which was successfully replacing wooden railroad bridges with iron ones. By the 1870s he was concentrating on steel manufacturing, ultimately creating the Carnegie Steel Company. In 1901 he sold that business for $250 million.

Carnegie then retired and devoted the remainder of his life to philanthropy. Even before selling Carnegie Steel he had begun to consider what to do with his immense fortune. In 1889 he wrote a famous essay entitled "The Gospel of Wealth," in which he stated that wealthy men should live without extravagance, provide moderately for their dependents, and distribute the rest of their riches to benefit the welfare and happiness of the common man--with the consideration to help only those who would help themselves. "The Best Fields for Philanthropy," his second essay, listed seven fields to which the wealthy should donate: universities, libraries, medical centers, public parks, meeting and concert halls, public baths, and churches. He later expanded this list to include gifts that promoted scientific research, the general spread of knowledge, and the promotion of world peace. Many of these organizations continue to this day: the Carnegie Corporation in New York, for example, helps support "Sesame Street."

Because of his background, Carnegie was particularly interested in public libraries. At one point he stated a library was the best possible gift for a community, since it gave people the opportunity to improve themselves. His confidence was based on the results of similar gifts from earlier philanthropists. In Baltimore, for example, a library given by Enoch Pratt had been used by 37,000 people in one year. Carnegie believed that the relatively small number of public library patrons were of more value to their community than the masses who chose not to benefit from the library.

Carnegie divided his donations to libraries into the "retail" and "wholesale" periods. During the retail period, 1886 to 1896, he gave $1,860,869 for 14 endowed buildings in six communities in the United States. These buildings were actually community centers, containing recreational facilities such as swimming pools as well as libraries. In the years after 1896, known as the wholesale period, Carnegie no longer supported urban multipurpose buildings. Instead he gave $39,172,981 to smaller communities that had limited access to cultural institutions. His gifts provided 1,406 towns with buildings devoted exclusively to libraries. Over half his grants were for less than $10,000. Although most of the towns receiving gifts were in the Midwest, in total 46 states benefited from Carnegie’s plan.

Andrew Carnegie stopped making gifts for library construction following a report made to him by Dr. Alvin Johnson, an economics professor. In 1916 Dr. Johnson visited 100 of the existing Carnegie libraries and studied their social significance, physical aspects, effectiveness, and financial condition. His final report concluded that to be really effective, the libraries needed trained personnel. Buildings had been provided, but now it was time to staff them with professionals who would stimulate active, efficient libraries in their communities. Libraries already promised continued to be built until 1923, but after 1919 all financial support was turned to library education.

When Andrew Carnegie died in 1919 at age 84, he had given nearly one-fourth of his life to causes in which he believed. His gifts to various charities totalled nearly $350 million, almost 90 percent of his fortune. Carnegie regarded all education as a means to improve people’s lives, and libraries provided one of his main tools to help Americans build a brighter future.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How did progress and industrialization affect Carnegie, both when he was young, and later in life?

2. How much formal education did Carnegie have? What factors contributed to his interest in books and reading?

3. What did Carnegie believe wealthy people should do with their money? Why did he think that? Do you agree?

4. How did supporting libraries fit with Carnegie's past and his beliefs?

Reading 1 was compiled from George S. Bobinski, Carnegie Libraries (Chicago: American Library Association, 1969); Andrew Carnegie, Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, reprint (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1920 [1986]); Barry Sears, "On the Trail of Carnegie Libraries," Antiques and Collecting (February 1994); Gerald R. Shields, "Recycling Buildings for Libraries," Public Libraries (March/April 1994).

Determining the Facts

Document 1: Schedule of Questions for Communities Applying for a Carnegie Library

Carnegie officials required applicants to provide the following information.

Free Public Library

1. Name of Town___________________________________

2. Population______________________________________

3. Has it a Library at present?__________________________

4. Number of books (excluding government reports)?________

5. Circulation for the last year?_________________________

6. How is Library housed?____________________________

7. Number of rooms, their measurements and uses?_________

8. Finances according to the last annual report:

|

Receipts |

Expenditures |

9. a) Rate at which municipality will pledge annual support (with a tax levy) if building is obtained___________________

b) What is the highest rate of tax levy allowed by law?_________________________

c) How much income would this rate have yielded for the last five years?_________________________

10. Is the requisite site available?_______________

11. Amount, if any, already collected toward building______________

"To facilitate Mr. Carnegie’s consideration of your appeal, will you oblige by filling in the above, and return with a statement of any particulars likely to assist in making decision? It is necessary to give explicit answers to each question, as in the absence of such, there is no basis for action, and the matter will be delayed pending further communication."

(Adapted from the three versions used by James Bertram, Carnegie’s secretary)

The form below was designed by Carnegie officials to show that the community accepted the library grant as well as the specified responsibilities.

A Resolution to Accept the Donation of Andrew Carnegie

Whereas, Andrew Carnegie has agreed to furnish_______________ Dollars to the _______________ (name of community) to erect a Free Public Library Building, on condition that the said community shall pledge itself by a Resolution of Council, to support a Free Public Library, at a cost of not less than _______________ Dollars a year, and provide a suitable site for the said building.

Now therefore be it resolved by Council of _________ (name of community) that said community accept said donation, and it does hereby pledge itself to the requirements of Andrew Carnegie. Resolved that it will furnish a suitable site for said building when erected, at a cost of not less than ____________ Dollars. Resolved that an annual levy shall hereafter be made upon the taxable property of said community sufficient in amount to comply with the above requirements.

(The signatures of the clerk and mayor and the witnessing statement of the clerk followed)

Questions for Document 1

1. What type of information does the form ask for?

2. Why would Carnegie want to know if the community already had a library? Why would he want to know about how much money the community could supply for maintenance?

3. Why would Carnegie make the community sign a contract in which they promise to provide a site and support for the library for which he will donate the money?

Document 1 was adapted from George S. Bobinski, Carnegie Libraries (Chicago: American Library Association, 1969).

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Obtaining a Carnegie Library

Andrew Carnegie began his philanthropy to public libraries at a time when they desperately needed help. Even with tax levies, many communities could not afford to build their own library. Most libraries were collections of books located in highly unusual places: wooden shacks, millinery shops, offices, stables, and churches. One town even had their "library" in a rest room, where the matron doubled as a librarian.

It was during his "wholesale" period of giving that Carnegie helped communities like these obtain libraries. A town in any English-speaking nation desiring a grant began by writing a letter of request to Carnegie’s secretary, James Bertram, who then sent them a Schedule of Questions similar to Document 1. Carnegie and Bertram were willing to consider any completed application.

Some people, however, did not even want to ask for a grant. They objected to receiving money from Carnegie, who after 1892 had developed a reputation as a ruthless businessman. Carnegie had always said that when workers were on strike, plants such as his steel mills should be shut down. Strikebreakers (often known as "scabs") should never be used, and disputes should be peaceably negotiated.

In July 1892 the union workers at Carnegie’s Homestead steel plant near Pittsburgh went on strike. Carnegie was at his home in Scotland, leaving Henry Clay Frick, second in command at Carnegie Steel, in charge. Frick decided to stop negotiating, and he locked the workers out of the plant. Frick, who was more aggressive than Carnegie in asserting management’s authority, soon hired 300 Pinkerton detectives from Pinkerton National Detective Agency to protect the plant and the nonunion work force he intended to hire. When the Pinkerton men arrived via rafts on the Monongahela River, they were met by an army of angry strikers. The next several hours of gunfire and other attacks resulted in a number of deaths and injuries. The Pennsylvania national guard finally restored order and protected the plant until the union broke that fall. Although Carnegie did not call in the detectives, he also made no effort to tell Frick not to do so, nor did he settle the strike after the violence erupted.

Homestead forever stained Carnegie’s reputation. Some people accused him of building his fortune on the backs of underpaid labor; others found it ironic that he would build libraries for working men who, because of long hours on the job, could not use them. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch illustrated the feelings of many when it wrote, "Ten thousand ‘Carnegie Public Libraries’ would not compensate for the direct and indirect evils resulting from the Homestead strike."¹

For the most part, however, communities still chose to complete their applications. Though Carnegie readily granted money, he also placed several conditions on his gifts. Municipalities had to own the site on which the library would be built, which often meant spending taxpayer money. The property also had to be large enough that the library could be expanded if demand rose.

The maintenance pledges that were another part of the contract could prove a major stumbling block. Carnegie required that the grant recipients agree to pay each year an amount equal to 10 percent of his gift to maintain the building his donation provided. He believed that "the community which is not willing to maintain a Library had better not possess it," but opponents argued that their taxes were already too high and that Carnegie’s rules would raise them even more.

The designs towns wanted for their libraries also caused problems. Until 1908, communities that satisfied the site and maintenance pledges were free to build whatever they saw fit. However, Carnegie and Bertram thought that many of the plans were not practical, because they had expensive exteriors and inefficient interiors. For instance, Bertram discouraged fireplaces, believing that they wasted space and benefited only those closest to the heat.

In 1908 Bertram began exerting more control over designs. For three years he required grant recipients to submit plans before building began, and then he wrote a book entitled Notes on Library Bildings [sic]. Sent to every community that won a grant, Notes reflected the thinking of leading architects of libraries. It contained minimum standards and six model floor plans that provided the greatest amount of usable space consistent with good taste. It suggested a basement 9 to 10 feet high and 4 feet below natural grade and a second level 12 to 15 feet high. The most commonly adopted of the plans called for a main floor with an adult reading area on one side, a children’s area on the other, and the librarian’s desk between the two (see Drawing 1, Plan B). The front door was located in the middle, opposite the librarian. The exterior was left to the discretion of the community, but they were warned to keep the structure plain and dignified. Bertram wanted usable, practical libraries, not elaborate "Greek Temples."

Communities which failed to meet Bertram’s increasingly demanding standards found their designs rejected. Using some of the simplified spellings Carnegie advocated, Bertram sent the following letter to one town in Washington state: "...the plans...in no way interpret the ideas exprest in Notes on Library Bilding. A school-boy could do that better than the plans show. If the architect’s object had been how to waste space instead of how to economize it, he could not have succeeded better....If the architect cannot make a better attempt at interpreting the Notes on Library Bilding, I shall be pleased to put you in communication with architects who have shown their ability to do so."²

Bertram’s standards combined with the tastes of the times to create many libraries that looked similar. The high ceilings and the second-level public areas suggested by Bertram resulted in spacious interior rooms with splendid natural lighting and ventilation. Due to these qualities, the need for a flight of stairs from the street arose. The stairs, in fact, are commonly regarded as the identifying characteristic of a Carnegie library. Some feel that Carnegie felt anybody who wanted to read ought to be willing to climb a few steps. It is true he thought that ambitious young people would be the primary users of these libraries, and that they would presumably not be troubled by a few stairs. Some say the stairs carry a symbolic message, as in "thirteen steps to wisdom." The stairs, however, created problems for older people and those who have difficulty walking.

Although Bertram insisted on the implementation of his ideas about basic design, he did not try to influence style, except to hope that it would be dignified. Perhaps this explains to some extent the frequent use of classical architectural elements in these buildings, but it is not true that stylistic similarities are the result of dictates by Bertram and Carnegie.

One matter of design, however, may be indirectly related to Carnegie’s involvement. Although some big-city libraries made extensive use of sandstone, a large majority of the existing Carnegie libraries are brick. This may be explained by the fact that they were intended to be permanent public buildings. However, it may not have escaped the notice of city officials that brick, while more expensive in terms of construction costs, is less expensive than other materials to maintain. The city only had to take care of the building, while Carnegie agreed to pay for materials. None of the libraries are wood, even in communities where the lumber industry was the mainstay of the economy.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Considering the events surrounding the Homestead Strike, would you have accepted Carnegie's donation? Why or why not?

2. What were some of the obstacles that slowed communities' attempts to obtain a Carnegie library?

3. Why did Carnegie place certain requirements on communities wanting to obtain a library? Do you think his requirements were reasonable?

4. Why did James Bertram write his book?

Reading 2 was compiled from James H. Vandermeer, "Carnegie Libraries of Washington Thematic Resource" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982.

¹ Louis M. Hacker, The World of Andrew Carnegie (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1968). ² James H. Vandermeer, "Carnegie Libraries of Washington Thematic Resource" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982, Section 8, page 3.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Examples of Carnegie Libraries

Medford Free Public Library, Medford, Wisconsin

A farmer named A. E. Harder turned out to be the first permanent settler of what became the town of Medford, Wisconsin. In December 1872 he established a homestead in what at that time was the remote north-central section of the state. Additional settlers came in 1873, and that same year a depot for the Wisconsin Central Railroad Company was built. Many of the original promoters of the Wisconsin Central railway were natives of Massachusetts, and borrowed the name "Medford" from a town near Boston. Much of the early industry in the area revolved around logging.

As the town grew it created institutions like schools and libraries. In Medford, as in many other towns, women controlled the founding and operation of the library. According to David L. Macleod, author of Carnegie Libraries in Wisconsin, many of these women hoped to draw men away from the saloons. In 1902 the Medford Women’s Club joined with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to organize a center to encourage reading and the dissemination of information. The WCTU erected a new building, part of which was to be used for a free public library. The Women’s Club contributed $100 toward its construction. The library operated there for the next 15 years.

A formal library board met for the first time in January 1903 and decided to support the library by soliciting contributions from the public. This campaign resulted in the collection of $75 for equipment such as shelves and tables, and $50 for the purchase of books. Benefit talent shows and Opera Hall events helped raise additional funds, and the city government began making contributions as well.

The library officially opened on February 23, 1903. Medford had 1,758 residents at the time, and the library issued 549 "borrower’s cards." In 1909 the library moved into a larger room in the Temperance Hall, but four years later even that space was considered inadequate. In 1913 the library board decided to apply to the Carnegie Foundation for a grant to construct a library building.

The Carnegie Foundation accepted Medford’s application in May 1913. The city agreed to continue its annual appropriation of $600 and the foundation donated $6,000 for a new building. The city-appointed library board chose a site at the end of Main Street. This location, on the edge of the downtown district, was considered a desirable location by early 20th-century library planners, since it made the library easily accessible from the center of town.

Even after Medford received its grant, women’s clubs continued to play an important role in the town’s library. In the fall of 1915, the Medford Woman’s Alliance was organized to assist in maintaining the new library. In 1916 the Alliance helped furnish the new building by donating a mahogany desk, shades, and plant stands. In subsequent years it made further donations.

The Medford Free Public Library had its grand opening in 1917 on Washington’s birthday. The freestanding rectangular block, approximately 50 feet long and 30 feet wide, was built in a style that has become known as the Prairie School, popular in the early 20th century for small-scale library facilities. The Prairie School derived its name from its emphasis on horizontal lines, as though the building had grown naturally out of the long, low landscape of the Midwestern prairie. The one-story Medford library is set into a hillside that slopes down toward the rear of the building. Its foundations are made from concrete, while the walls are brick. The attic and underside of the eaves are stuccoed, and the low, hipped roof is now asphalt.

The interior of the building has changed over the years. Initially all the books were shelved along the walls of the rectangular first floor room. Though this system could accommodate the original collection of 2,221 volumes, by 1936 the library had expanded to 5,637 books and remodelling was necessary. Numerous shelving units were added as the collection continued to grow. In 1984 the number of items in the library was estimated at 21,900. However, due to limited space, a new library was constructed down the street and the Medford Free Public Library building now houses the local Chamber of Commerce.

Carnegie Free Library, Connellsville, Pennsylvania

Connellsville sits in one of the many valleys which run throughout the Allegheny Mountains of southeastern Pennsylvania. Thirty-five miles southeast of Pittsburgh, the town formed part of the network of raw materials and manufacturing plants that made the region the center of America’s industrial revolution. Connellsville’s most prominent product was its coal and coke, which five different railroads carried to fuel the iron and steel mills of companies such as Carnegie Steel.

Through the gift of a library, some of the wealth Andrew Carnegie had drawn from the Connellsville area returned to the town. In 1899 it asked Carnegie for a $50,000 grant to build a new library to house the growing collection it was already developing. He agreed, "provided a suitable site is furnished and the [town] council agrees to grant a fund annually to maintain and operate the library."

Meeting these conditions, however, proved difficult. The town council, the school board, and the General Library Committee agreed that the proper location for the proposed library building was the old cemetery that was in the hands of the school board. The school board was instructed to condemn the old "Connell Grave Yard" (given to the town by Zachariah Connell, its founder), after which the land would be donated for the library. The school board engaged an attorney and the process of acquiring the cemetery began. It took almost one year to condemn the ground, remove the bodies, and reinter them in Chestnut Hill Cemetery.

These actions caused a great deal of dissension in the community. Objections were raised to using the cemetery for the project, with many feeling that it was ghoulish to exhume the bodies. Others complained because relatives had to bear the expense of exhumation and reinterment.

Another group complained about the new library because of its expense. On April 16, 1900, the town council levied a one mill tax--that is, a 1/1,000 tax per dollar of property owned, or 1 cent for every 10 dollars--to pay for supplies and maintenance. On April 18 the opponents of the new tax wrote to Carnegie protesting "against burdening the town with a debt it can ill afford to incur under existing conditions." They attacked library advocates, saying these men had neither given any monies themselves nor solicited voluntary contributions. Instead, said the critics, supporters had obligated residents to pay higher taxes and invited litigation over use of cemetery grounds. Carnegie’s office rejected these complaints because the town council, which had the power to levy taxes, had approved the agreement. Carnegie believed the council was elected by the citizens of Connellsville and that its actions reflected the interests of the people.

Though some opposition to the tax continued for the next several years, library construction began in 1901. At the cornerstone laying, one of the speakers summed up the importance many in the community placed on the new building. "In laying the cornerstone of this building," he said, "you are not merely putting in place an inorganic block. You are laying the foundation of increased knowledge, happiness, enjoyment and improvement in your community. Within the walls to be erected, you and your sons and daughters and generations yet to come, can survey the whole horizon of human existence and achievement."¹

The "inorganic block" the speaker mentioned was a massive structure for a town of Connellsville’s size. Two stories tall with a full basement, the library sits on a small hill near Connellsville’s business district. Nearly 100 feet wide and 75 feet deep, the building was made primarily from stone quarried in Ohio. The library’s style is best described as neoclassical, since it contains elements borrowed from Greek and Roman architecture.

Today, the library’s main activities occur on the first floor. The two largest spaces are the children’s reading room and the adult reference room. There are plans to restore the reference room to its original 1903 appearance. Other rooms hold periodicals, book stacks, and offices. The second floor has an auditorium, houses the Connellsville Historical Society, and houses the local history library for genealogy.

Questions for Reading 3

1. How would you respond to someone who says that Andrew Carnegie created the Medford Library?

2. Why do you think women had such a large role in the development of the library?

3. Do you think it was acceptable to move the graveyard? Why or why not?

4. Why would Connellsville, which had fewer than 15,000 people, receive such a big grant?

Reading 3 was adapted from from Amy Alexandra Ross, "Medford Free Public Library" (Taylor County, Wisconsin) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1993; and Carmel Caller, "Carnegie Free Library" (Fayette County, Pennsylvania) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1981.

¹ Carmel Caller, "Carnegie Free Library" (Fayette County, Pennsylvania) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1981, Section 8, page 4.

Determining the Facts

Table 1: Distribution of Carnegie Libraries, 1920

|

State |

Population |

Libraries |

Libraries |

|

State |

Population |

Libraries |

Libraries |

|

AL |

2,348,174 |

14 |

6.0 |

|

MT |

548,889 |

17 |

31.0 |

|

AZ |

334,162 |

4 |

12.0 |

|

NE |

1,296,372 |

69 |

53.2 |

|

AR |

1,752,204 |

4 |

2.3 |

|

NV |

77,407 |

1 |

12.9 |

|

CA |

3,426,861 |

142 |

41.4 |

|

NH |

443,083 |

9 |

20.3 |

|

CO |

939,629 |

35 |

37.2 |

|

NJ |

3,155,900 |

35 |

11.1 |

|

CT |

1,380,631 |

11 |

8.0 |

|

NM |

360,350 |

3 |

8.3 |

|

DE |

223,003 |

0 |

0 |

|

NY |

10,385,230 |

106 |

10.2 |

|

DC |

437,571 |

4 |

9.1 |

|

NC |

2,559,123 |

10 |

3.9 |

|

FL |

968,470 |

10 |

10.3 |

|

ND |

646,872 |

8 |

12.3 |

|

GA |

2,895,832 |

24 |

8.3 |

|

OH |

5,759,394 |

105 |

18.2 |

|

ID |

431,866 |

10 |

23.2 |

|

OK |

2,028,283 |

24 |

11.8 |

|

IL |

6,485,280 |

106 |

16.3 |

|

OR |

783,389 |

31 |

39.6 |

|

IN |

2,930,390 |

164 |

56.0 |

|

PA |

8,720,017 |

58 |

6.6 |

|

IA |

2,404,021 |

101 |

42.0 |

|

RI |

604,397 |

0 |

0 |

|

KS |

1,769,257 |

59 |

33.3 |

|

SC |

1,683,724 |

14 |

8.3 |

|

KY |

2,416,630 |

23 |

9.5 |

|

SD |

636,547 |

25 |

39.3 |

|

LA |

1,798,509 |

9 |

5.0 |

|

TN |

2,337,885 |

13 |

5.5 |

|

ME |

768,014 |

17 |

22.1 |

|

TX |

4,663,228 |

32 |

6.9 |

|

MD |

1,449,661 |

14 |

9.6 |

|

UT |

449,396 |

23 |

51.2 |

|

MA |

3,852,356 |

43 |

11.2 |

|

VT |

352,428 |

4 |

11.3 |

|

MI |

3,668,412 |

61 |

16.6 |

|

VA |

2,309,187 |

3 |

1.3 |

|

MN |

2,387,125 |

65 |

27.2 |

|

WA |

1,356,621 |

43 |

31.7 |

|

MS |

1,790,618 |

11 |

6.1 |

|

WV |

1,463,701 |

3 |

2.0 |

|

MO |

3,404,055 |

33 |

9.7 |

|

WI |

2,632,067 |

63 |

23.9 |

|

MT |

548,889 |

17 |

31.0 |

|

WY |

194,402 |

16 |

82.3 |

Questions for Table 1

1. Identify the number of Carnegie libraries in your state and determine your state's population in 1920.

2. Which state has the largest number of libraries? the lowest?

3. Which state has the highest number of libraries per million? the lowest?4. Which state has the highest population? the lowest?

5. Based on your readings and Map 1, what conclusions can you draw from this data?

Visual Evidence

Drawing 1: Sample building plans as presented in James Bertram's Notes on Library Bildings [sic].

Questions for Drawing 1

1. Why do you think that so much space was dedicated to the children's room on both suggested floor plans?

2. What do you think the rectangles on the floor plans represent? Where do you think the books were housed?

3. Compare Plan B and Plan C. What differences, if any, are there between the two plans? Why do you think the options are so similar?

Visual Evidence

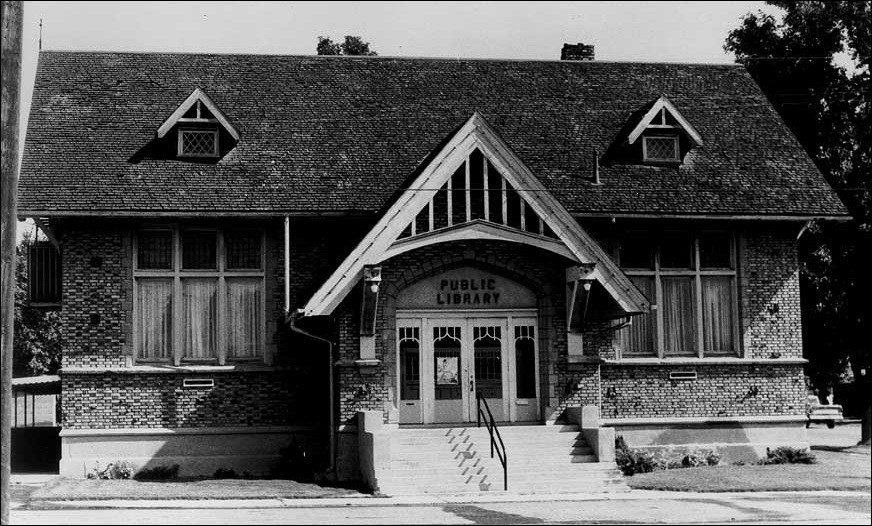

Photo 1: Medford Free Public Library, Medford, Wisconsin.

National Park Service

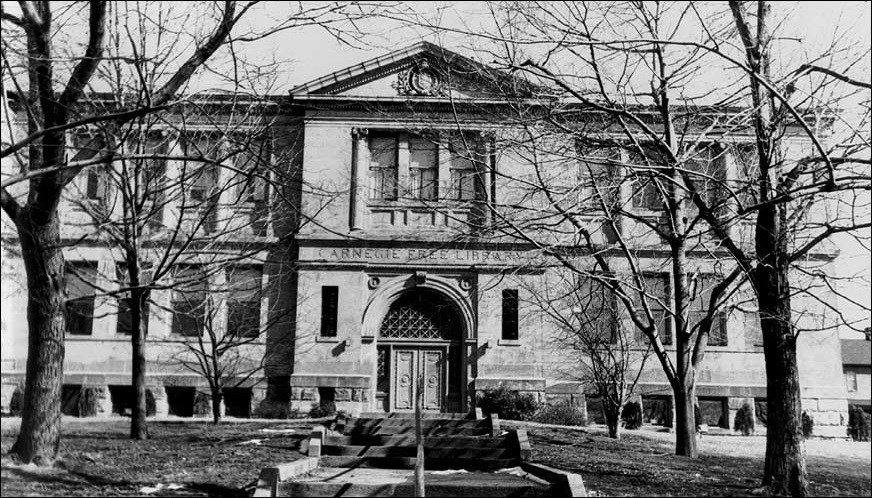

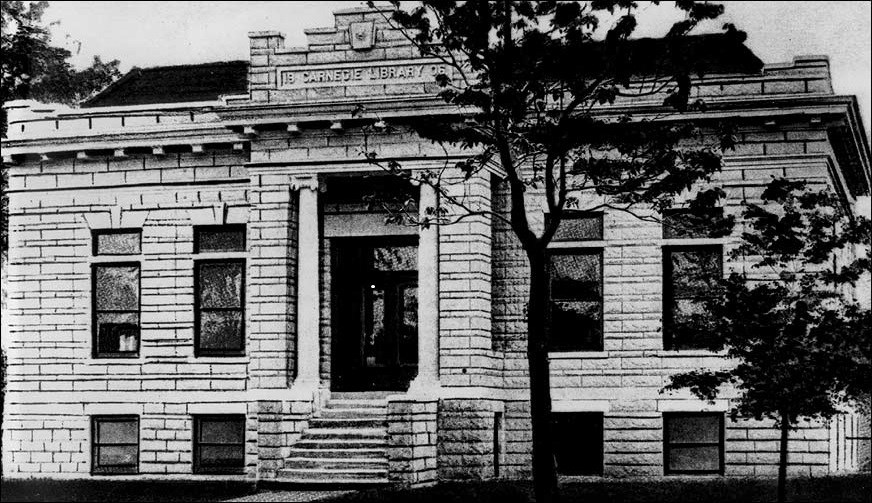

Photo 2: Carnegie Free Library, Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

National Park Service

Photo 3: Richfield Public Library, Richfield, Utah.

National Park Service

Photo 4: Carnegie library, Spokane Washington.

National Park Service

Photo 5: Carnegie library, Girard, Kansas.

National Park Service

All of the libraries pictured came from Carnegie's "wholesale" period of giving.

Questions for Photos 1-5

1. What are the similarities and differences between the libraries. Do you think you would be able to identify a "Carnegie library"? Why or why not?

2. To what extent have Carnegie and Bertram lived up to their claim that they did not care about the exterior design? What factors do you think influenced the exterior design of the libraries in the photos?

3. Do the large windows fit with Bertram's goals of efficient buildings? Do you think it would be practical to have such large windows on all sides of the libraries?

Questions for Illustration 1

1. When did this cartoon appear? Who are the various people in the picture? What are they doing?

2. What seems to be the artist's main point? How does this fit with the information you learned in the readings?

3. The cartoon suggests Carnegie's donations were tainted. Was Carnegie responsible for the Homestead strike? Why or why not?

4. Should communities have considered how Carnegie made his money before deciding whether to accept his gift? Why or why not?

Putting It All Together

Carnegie libraries illustrate many important aspects of turn-of-the-century America. The money to build them came from a man whose beliefs mixed aggressive capitalism with a commitment to public philanthropy. Carnegie’s gifts were built on efforts already begun by others. These library supporters had a variety of motives, including a belief in learning and an attempt to shape society along the lines they preferred. The following activities should help students clarify their thinking about these subjects.

Activity 1: Additional Research on Carnegie

Divide students into groups of four or five. One student should read Carnegie’s essays on the responsibility of rich men, then research his homes and other possessions. Another student should learn about the conditions in his factories, while the rest of the group learns about Carnegie’s other charities. The group should reassemble and decide collectively whether he lived up to his words. Have each group give their report to the entire class and then follow with a class discussion.

Activity 2: Famous Philanthropists

Have students role play. Some of the students should assume the identity of one of the great American philanthropists of the period--Rockefeller, Mellon, Vanderbilt, Morgan, etc.--and then research their lives. Other students should be journalists who also will research the lives of these men, so they can ask them about their gifts and about how they made their money. Have a public forum or press conference in which each of the famous figures tries to show why he, not Carnegie, was America’s greatest philanthropist.

Activity 3: Spending a Fortune

Tell the students they have each come into a fortune of $100 million. Have them write an essay in which they describe how much of the money they would keep for themselves, how much they would give to their families, and how much they would give to charity. Once they decide how philanthropic they will be, have them explain which groups they would give their money to, and why. Have the class discuss their choices.

Activity 4: Libraries in the Local Community

Have students research the history of their local library. Did the community receive a gift from Carnegie or some other philanthropist? What existed before the first official library? How does (did) that building compare to the designs in the plans and photographs in this lesson? How is the public library supported today? Have students write a report, create a time line, or design an exhibit that shows the history of their community’s library.

Carnegie Libraries:The Future Made Bright--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright, students can examine the history of public libraries in the United States, the life of Andrew Carnegie, and the libraries that he supported through his philanthropy between the 1886 and 1919. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Library of Congress

Visit the Digital Collections page to search for historical, architectural, and photographic documents on Carnegie libraries as well as Andrew Carnegie. Also search for information on industrialization and labor unions in America.

Andrew Carnegie and The American Experience

PBS and American Experience produced numerous documentary films on the life of Andrew Carnegie. The PBS site provides a synopsis of the films, further readings, as well numerous resources for teachers. To find all the films on Andrew Carnegie, search "Carnegie." For a listing of all programs, click on programs A-Z.

The Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum

The Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum website tells the story of Carnegie's humble birth in Scotland and of his immigration to the United States as a child in the 1840s. The Web site also features art and artifacts related to Carnegie's life, both in Scotland and in the U.S.

Tags

- science

- art and education

- gilded age

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- pennsylvania

- pennsylvania history

- wisconsin

- wisconsin history

- progressive era

- early 20th century

- carnegie

- carnegie libraries

- carnegie free library

- industry

- steel

- industrialization

- science and technology

- twhplp

- utah

- washington

- kansas