At the onset of the Civil War, neither side was prepared for a prolonged conflict, both believing that the war would not last long. As a result, neither side considered how to house and care for the thousands of enemy soldiers who would eventually be taken prisoner. As the war continued, however, the necessity of caring for these prisoners became more apparent and critical.

"...hell on Earth where it takes 7 of its ocupiants (sic) to make a Shadow." Sgt. David Kennedy, 9th Ohio Cavalry, of Andersonville prison

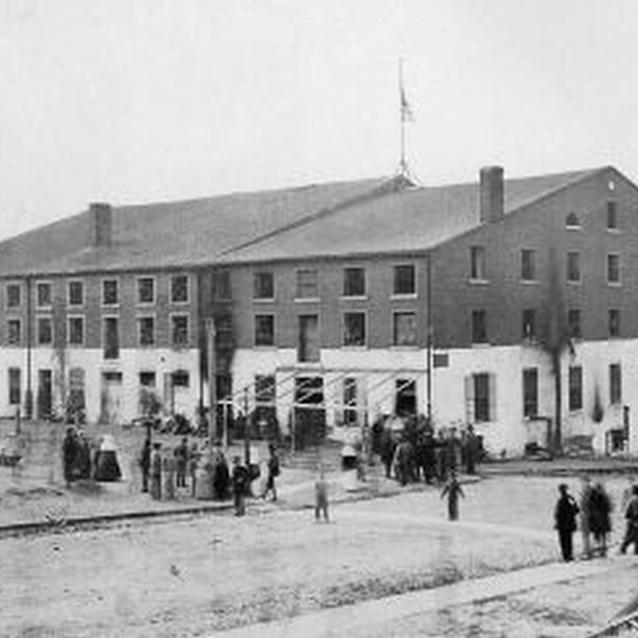

A Prison Near Andersonville, Georgia

Library of Congress

Following the war's early battles, both sides used an informal parole system, which often occurred right on the battlefield. The prisoners would state on their honor that they would return home and no longer fight until officially exchanged. This system was quickly found to be impractical, as many prisoners violated the terms of their paroles and continued to fight.

A formal prisoner exchange system was devised in July 1862. The system was governed by the Dix-Hill Cartel (named for Union General John Dix and Confederate General D.H. Hill, the primary architects of the cartel), which specified the worth of each soldier by rank. For example, one captain alone was worth sixty privates. However, the cartel soon broke down and the Union realized that it was to their advantage not to exchange prisoners. As a result, both sides began preparing to house and feed large numbers of prisoners.

Commonly known as Andersonville, the military prison facility was officially named Camp Sumter, in honor of the county in which it was located. Construction of the camp began in early 1864 after the decision had been made to relocate Union prisoners to a more secure location.

Camp Sumter was only in operation for fourteen months. However, during that time, 45,000 Union soldiers were imprisoned there, of which nearly 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure.

The prison site initially covered approximately 16 1/2 acres of land, which was enclosed by a 15 foot high stockade wall. The prison was enlarged in June 1864 to 26 1/2 acres to compensate for overpopulation. The stockade was constructed in the shape of a parallelogram that was 1,620 feet long and 779 feet wide. Approximately 19 feet inside of the stockade wall was the "deadline," which the prisoners were not allowed to cross. If a prisoner stepped into this area, the guards in the "pigeon roosts," which were roughly thirty yards apart, were permitted to shoot them.

The earliest camps for Union prisoners were in and around Richmond, Virginia, capital of the Confederacy. By 1863, however, the prisoner population in Richmond had grown to the point that it caused a serious drain on the city's dwindling food supply. Additionally, Richmond was under constant threat of attack, so the Confederacy established large prison camps in remote locations, such as Andersonville, Georgia.

Deteriorating Conditions

Library of Congress

The first prisoners arrived at Camp Sumter in February 1864. Over the course of the next few months approximately 400 prisoners arrived daily. Though designed to house only 10,000 prisoners, by June 1864 over 26,000 men were confined at Andersonville. Two months later, the population had swelled to 32,000, the most men it ever held at any one time.

In order to concentrate all resources on its army, the Confederate government was chose not to provide the prisoners with adequate housing, food, clothing, and medical care. These terrible conditions, combined with the breakdown of the prisoner exchange system over the Confederacy's refusal to treat African American soldiers as anything but slaves, caused the prisoners to suffer greatly and resulted in a high mortality rate.

On July 9, 1864, Sergeant David Kennedy of the 9th Ohio Cavalry wrote in his diary:

"Wuld (sic) that I was an artist & had the material to paint this camp & all its horrors or the tongue of some eloquent Statesman and had the privleage (sic) of expressing my mind to our hon, rulers at Washington, I (sic) should glorery (sic) to describe this hell on Earth where it takes 7 of its ocupiants (sic) to make a Shadow."

When General William T. Sherman's Union forces occupied Atlanta on September 2, 1864, placing Federal cavalry columns within easy striking distance of Andersonville, most of the prisoners were moved to other camps in South Carolina and coastal Georgia. From that point until May 1865, Andersonville was operated on a smaller basis.

When the war ended, Captain Henry Wirz, the stockade commander, was arrested and charged with conspiring with high Confederate officials to "impair and injure the health and destroy the lives...of Federal prisoners" and "murder, in violation of the laws of war." Such a conspiracy never existed, but anger and indignation throughout the North over the conditions at Andersonville demanded appeasement. Wirz was found guilty by a military tribunal and was hanged in Washington, D.C. on November 10, 1865. A monument to Wirz, erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, stands today in the historic town of Andersonville.

After the War

Library of Congress

In July 1865, Clara Barton accompanied a United States Army Quartermaster Department expedition comprised of laborers and soldiers, and a former prisoner named Dorence Atwater to the Andersonville cemetery to identify and mark the graves of the Union dead. As a prisoner, Atwater was assigned to record the names of deceased Union soldiers. Fearing loss of the death record at war's end, Atwater made his own copy in hopes of notifying the relatives of some 12,000 dead interred at the site. Thanks to his list and the Confederate records confiscated at the end of the war, only 460 of the Andersonville graves had to be marked "unknown U.S. soldier."

The prison site reverted to private ownership in 1875. In December 1890 it was purchased by the Georgia Department of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union veterans' organization. Unable to finance improvements needed to protect the property, this group sold it for one dollar to the Woman's Relief Corps (WRC), the national auxiliary of the GAR. The WRC made many improvements to the area with the idea of creating a memorial park. Pecan trees were planted to produce nuts for sale to help maintain the site and states began erecting commemorative monuments. The WRC built the Providence Spring House in 1901 to mark the site where, on August 9, 1864, a spring burst forth during a heavy summer rainstorm - an occurrence many prisoners attributed to divine providence. The fountain bowl in the Spring House was purchased through funds raised by former Andersonville prisoners.

In 1910 the Woman's Relief Corps donated the prison site to the people of the United States. It was administered by the War Department and its successor, the Department of the Army, until its designation as a national historic site by Congress in October 1970. Since July 1, 1971, the site has been administered by the National Park Service.

Last updated: November 18, 2019