Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

Camp Misty Mount: A Place for Regrowth (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

The gentle Hunting Creek water gap in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains has long drawn people to it. Although the Susquehannoughs, northern Iroquois, and Algonquins who lived in the area had battled one another for many years, these tribes agreed to preserve this bountiful place as neutral ground. Starting in the 1730s European Americans arrived in increasing numbers, as second-generation Americans and German immigrants pushing out from Philadelphia turned southwest at the Susquehanna River. Throughout the 18th century, Germans, Swiss, and Scots-Irish continued to appear. Some trudged on west in search of fertile lands, but many settled the mountainsides. One of the area’s largest communities became known as Mechanics Town, a name reflecting its thriving manufacturing and service industries.

Crucial to successful settlement were trees. Originally regiments of them covered the mountainsides, but their ranks began to fall as European Americans moved in. Settlers cut them to build simple but sturdy log homes and to clear fields for farming. On creeks water-powered sawmills popped up, producing lumber for more elaborate houses or for distant markets. When an iron furnace was built near Mechanics Town, larger areas were clear-cut for the charcoal needed to feed its voracious appetite. By the beginning of the 20th century, most hills had been stripped of their guardians and bore only scars of erosion. Starting in the 1930s, however, people began to reclaim the land. The story of how the area near Hunting Creek regained its forest is the story of Camp Misty Mount.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration files, "Camp Misty Mount Historic District" (with photographs) and "Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Architecture at Catoctin Mountain Park," and records in the archives of Catoctin Mountain Park. It was written by Debra Mills, a Park Ranger at Catoctin Mountain Park. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on the growth of industry in colonial America, on job programs of the Depression, or in a course examining the importance of resource conservation. Students will strengthen their skills of observation, research, and analysis of a variety of sources.

Time period: Early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"Camp Misty Mount: A Place for Regrowth" relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929 to 1945)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands the New Deal and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the impact of the New Deal on workers and the labor movement.

-

Standard 2C- The student understands opposition to the New Deal, the alternative programs of its detractors, and the legacy of the New Deal.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

"Camp Misty Mount: A Place for Regrowth" relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystems changes.

-

Standard K - The student proposes, compares, and evaluates alternative uses of land and resources in communities, regions, nations, and the world.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard J - The student uses economic reasoning to compare different proposals for dealing with a contemporary social issue such as unemployment, acid rain, or high quality education.

Find your state's social studies and history standards for grades Pre-K-12

Objectives for students

- To explain the important role that forests can play in a local economy.

- To outline the tasks completed at Misty Mount by the Works Progress Administration work force and explain why this government program had both local and national significance.

- To describe the concept of rustic architecture and explain why the style was so well suited for the construction of Campy Misty Mount.

- To compare the use of natural resources in the Catoctin Mountain area with the use of natural resources in their own region.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

- One map showing the main routes to the Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area in the 1930s;

- Two readings demonstrating the changing uses of Catoctin Mountain Forests and the construction of Camp Misty Mount;

- One document showing an estimation of labor and materials for camp buildings;

- Four photographs of rustic architecture and views of the forest;

- One drawing of Camp Misty Mount.

Visiting the site

Camp Misty Mount is part of the National Park Service’s Catoctin Mountain Park, located three miles west of Thurmont, Maryland, on state route 77. The park is open year-round during daylight hours. The visitor center is open daily from 10 a.m. until 4:30 p.m., with extended hours on weekends. Camp Misty Mount is available for individual cabin rental during certain times of the year. (The general public is excluded from the camp to assure the privacy and security of the cabin occupants.) For more information, visit the park Web pages.

Getting Started:

Inquiry Question

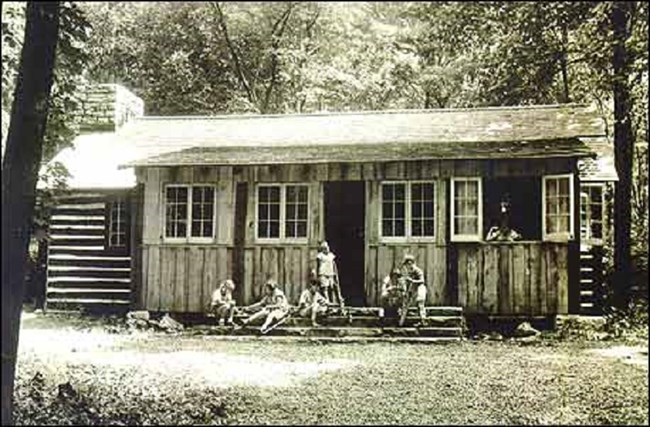

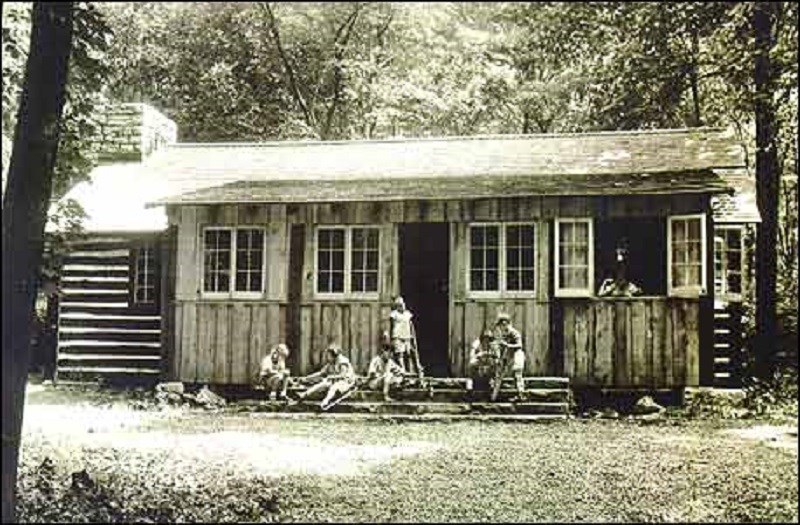

Examine the photo carefully, noticing in particular the children in the scene.

- Why might the children be staying at this cabin?

- Do you think they lived there?

Setting the Stage

Establishing a location for settlement depends on both the availability of resources and the ease of transportation. In the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland, the forest simultaneously provided an exceptional source of raw materials and an obstacle to farming and transport. Since settlers saw wood as an inexhaustible resource, they chose to cut at will so they could grow more crops and move more easily over the hilly terrain. This attitude toward the forest meant that by the beginning of the 20th century many of the areas mountain slopes stood bare. Most surviving trees then died during the next generation, as the Chestnut blight, a fungus originally from Asia, spread over the area.

The New Deal began the long process of reclamation and reforestation. Throughout the country the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built public recreation areas on damaged land like that in the Catoctin Mountains. These areas, called Recreational Demonstration Areas (RDAs), provided organized camps that enabled urban dwellers to escape the city and enjoy the benefits of nature. The section of the Catoctin Mountains near Thurmont, Maryland, was one of the sites selected to be developed into an RDA. Although most of the 46 RDAs established across the country were eventually turned over to their respective states for management, much of the Catoctin RDA was retained by the Federal Government as part of the National Park System. Today, Camp Misty Mount, one of the camps within the Catoctin RDA (now called Catoctin Mountain Park), is significant for several reasons. Not only is it a prime example of National Park Service rustic architecture, but it also represents a successful WPA project that continues to meet the recreational needs of individuals and organized groups from Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. Perhaps most important, Camp Misty Mount has helped the forest to regrow.

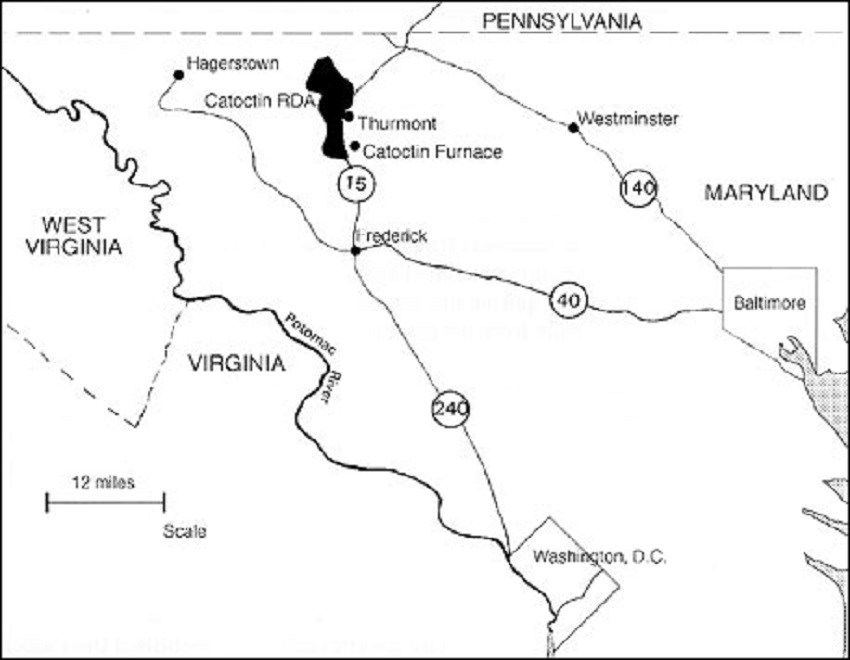

Locating the Site

Map 1: Main routes to the Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area, 1930s.

(map below)

Catoctin Furnace was the site of the Catoctin Iron Furnace established in 1774 to produce pig iron, which was in demand during this period. The need for charcoal to fuel the furnace contributed to the depletion of the forest. Thurmont was once named Mechanics Town and now serves as the eastern gateway to Catoctin Mountain Park. At the time Camp Misty Mount was built in the 1930s, it took people from Washington and Baltimore nearly a half day to drive to the site.

Questions for Map 1

- Note the location of Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Thurmont, and Catoctin Furnace. Calculate how far Washington, D.C. and Baltimore are from Catoctin RDA. Approximately how long would it take to get to Catoctin RDA from these locations today?

- What natural recreation areas are within two hours of your community?

Determining the Facts:

Reading 1: The Changing Uses of the Catoctin Mountain Forests

Farming and timber harvesting and jobs associated with the iron industry were the primary occupations of people living in the Catoctin Mountains during the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Several sawmills operated in the area, and wood—especially the abundant American Chestnut—was used for fuel, railroad ties, barrel staves, and mine supports. Thousands of additional acres were clear-cut to make charcoal for the Catoctin Iron Furnace. Other residents found work in the range of manufacturing industries that prospered in Mechanics Town, now known as Thurmont.

At the end of the 19th century the area’s economy began to decline. In the 1880s many local workers became unemployed when the furnace stopped using charcoal; those who survived this cutback lost their jobs later when the entire operation closed in 1903. Sawmills used up the remaining large timber by 1911; the last barrel stave factory closed in 1926, after the Chestnut blight, a fungus originally from Asia, had killed virtually all of that species. Years of poor farming practices and many fires from logging operations also had damaged the natural resources of the region.

Conditions in the area deteriorated as the 1930s continued. During the early part of the Great Depression, rural Maryland fared better than much of the country. While many urban residents found themselves without work, farms managed to provide an adequate living for their occupants. As a result many city dwellers returned to the country, which for a short time supported them as well. Several years of drought, however, combined with the increased population to overtax the local economy. Limited state aid was insufficient to ease these economic problems, and so in 1933 Maryland applied to participate in federal relief programs.

Maryland’s struggle coincided with a growing back-to-nature movement. Many influential people, including members of the Roosevelt administration, believed that Americans needed to move back to, or at least spend their leisure time in, a natural environment. A National Park Service study of the time illustrated these ideas:

Man’s loss of intimate contact with nature has had debilitating effects on him as a being which can be alleviated only by making it possible for him to escape at frequent intervals from his urban habitat to the open country....He must again learn how to enjoy himself in the out-of-doors by reacquiring the environmental knowledge and skills he has lost during his exile from his natural environment.¹

President Roosevelt’s New Deal contained programs that attempted to meet these goals and at the same time offer relief from the Great Depression. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration, for example, spent $5 million to acquire submarginal land—that is, agricultural property that did not provide its owners reasonable incomes—that would create new sites for public recreation. A series of federal agencies subsequently created 46 "Recreational Demonstration Areas" (RDA) across the country; these spots were either waysides along important highways, extensions to national parks, additions to state scenic areas, or camping areas. In addition to providing recreation, RDAs also contributed to efforts to conserve water, soil, and wildlife resources.

The federal and state governments soon identified the Catoctin Mountains of Frederick and Washington Counties, Maryland, as a potential camping area. The guidelines for that type of RDA called for 2,000 to 10,000 acres deemed submarginal, a metropolitan area of at least 300,000 people within a day’s round trip (considered at that time to be 50 miles), an abundance of water and building materials, and a generally interesting environment. Around the Catoctins much of the land was submarginal: of the 50 families relying on agricultural production, 8 were making a subsistence living from the land, 26 were cutting timber, and 16 were living on relief. The area was just under 50 miles from Baltimore and Washington, each of which far exceeded 300,000 people. Though most of the forest was gone, many large, dead trees remained; the area also had ample water. As a result, starting in 1934 the Federal Government sent letters to landowners in the area explaining the program and offering to purchase their land at a fair price. Enough landowners sold their property that the project began the next year.

The Catoctin RDA was scheduled to include four public recreation group camps and two picnic areas. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired hundreds of men: the number of workers at a given time averaged 250, but in one case rose as high as 595. In 1939, after the completion of the building program, workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)—another Depression-era relief program—occupied a camp and constructed waterlines, set stone walls, and trimmed trees. Each young man (ages 18-25) received $1.00 per day in wages, room, board, and the opportunity for some education. The men enrolled for six months and could reenlist. These federal relief programs ended abruptly with the onset of World War II. As the nation geared up for the coming battles, both industry and the military provided jobs for all who could be recruited.

Questions for Reading 1

- How did the original settlers make a living?

- What factors caused the collapse of the economy of the region?

- What do you think the National Park Service meant when it referred to the "debilitating effects" caused by "man’s loss of contact with nature"?

- What were the criteria for selection of RDA vacation sites? Why did they have to be close to cities? How might modern transportation methods have affected the criteria?

- How did the 18th- and 19th-century industries on Catoctin Mountain contribute to the site’s eligibility for the Recreational Demonstration Area program?

- What were the WPA and CCC? How did workers in those programs contribute to meeting the goals of the RDAs?

Compiled from Sara Amy Leach, "Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Architecture at Catoctin Mountain Park" (Frederick County, Maryland) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988.

¹ U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1941), 4.

Determining the Facts:

Reading 2: The Construction of Camp Misty Mount

The design and construction of Camp Misty Mount demonstrated some of the most important ideas about outdoor recreation of the 1930s. Misty Mount and the other campsites that formed part of the Catoctin RDA were known as "organization camps," an idea borrowed from several state parks. The primary goal of these camps was to provide educational and charitable groups a place where children could have an outdoor experience. Many of the campers came from cities or from families with limited incomes, and therefore without such a program they were unlikely to learn about or even spend time in outdoor settings.

Camp Misty Mount’s layout reflected how it served groups. It featured a central collection of buildings shared by all campers, including a dining hall, infirmary, and craft lodge. Beyond this hub were individual unit camps made up of several camper cabins, a lodge, a latrine, and perhaps a leader’s cabin. A network of hiking trails linked the buildings to miscellaneous sites, such as campfire rings, playing fields, and a swimming pool. These facilities and their arrangements were common to all organized camps built by the government.

While all RDA vacation spots shared a basic design, their exact layout varied. Plans took advantage of light, prevailing winds, and views from the cabins. Designers used the terrain to its best advantage in locating cabin foundations and the swimming pool. Trees slated to remain were boxed to protect them from injury during construction. Workers also took extra precautions to protect topsoil. At Catoctin, for example, the use of horses, rather than wagons or trucks, to haul logs to the sites helped minimize destruction of the landscape.

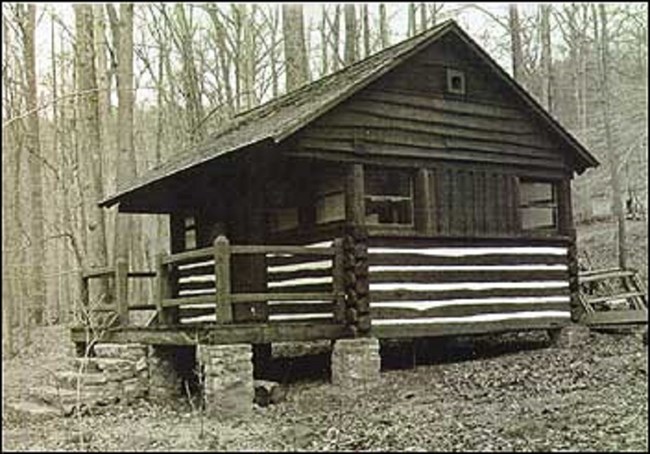

Albert Good’s Park Structures and Facilities, a book used in national parks, provided plans for the camp’s buildings. This guide called for "rustic" architecture, a style in which buildings used local materials, fit into the surrounding landscape, and appeared to have been built with traditional tools. At Camp Misty Mount one-story structures nestled into the natural profile of the land. Chestnut logs and waney board (random width, 1-inch thick poplar, pine, or oak boards with an exposed, wavy edge), wood shingles, and stone steps, foundations, and chimneys created a natural look. Features such as casement windows, braced posts, hand-wrought hardware, and interior roof trusses contributed romantic highlights.

The rustic exteriors called for in this guide perfectly fit the resources of the area. Fallen chestnut trees and other trees approved by the state forester for harvest provided wood for the log cabins. Some picturesque snags, or damaged trees, remained in place for aesthetic purposes and wildlife consideration. Since only 40 percent of the lumber was suited for planing into boards, designers used most fallen and cut logs in their entirety to build log cabins. Logs were pinned with poles from locust trees, and 4- to 8-inch by 26-inch roof shingles were made out of local red oak. Oak formed the interior tongue-in-groove floors, and chestnut, oak, or hemlock, and interior trim.

The government agencies responsible for building the camps in Catoctin Mountain Park justified their construction methods in the following planning document:

Justification for Using Logs in Construction of Group Camp Buildings

We have found it more economical to use chestnut logs in the construction of smaller buildings proposed for the area than it would be to purchase lumber for siding or board and batten.

There is a wealth of dead chestnut in the area that must be felled and as it takes about 15 years for this hardwood to decay beyond the fire hazard stage, it is necessary to make some disposition of the trees that are cut.

To date we have run through our sawmill approximately 80,000 board feet of chestnut and have found that only about 40 percent of the logs make good saw timber, whereas if only squared off it will be possible to use all the dead chestnut in building construction. The cost of labor for construction is practically the same for a log building as for one built entirely of sawed lumber. The cost of materials for the log building, taking into consideration the logging, transportation and squaring of the logs at the mill, will amount to about 15 percent less than the cost of materials for buildings constructed entirely of sawed lumber.

This would not be true if it were possible to cut all the lumber from this area, but it is not advisable to deplete the forest cover to this extent.

In addition to this, our project architect has made a study of the character and design of the old buildings in this section and in using the log type of construction in planning the improvements for the area, he is endeavoring to perpetuate the best architectural traditions whenever possible.

Justification of Individual Job/Job No. 608 - Timber

Harvest Supplement A

Purpose and Need

The purpose of this job is to manufacture lumber for the construction of Organized Group Camp C-1.

Useful lumber is produced from blighted chestnut and other dead or over matured timber in the area. Sawing this lumber at the Government owned mill on the project will result in a saving.

Execution

Rough lumber is being produced at the mill for $10.00 per thousand board feet, whereas lumber comparable to the most inferior that we are producing would cost $20.00 per thousand on the open market. Dressed tongue and groove flooring and ceiling can be produced at $9.00 per thousand, and if this lumber were taken to a private mill the charge for turning out a similar product would be $15.00 per thousand.

Questions for Reading 2

- For whom was Camp Misty Mount primarily designed? Why do you think the government wanted to give those people the opportunity to spend time in natural surroundings?

- What measures were taken to protect the trees that were growing in the project area? Why were horses used to harvest the timber?

- What are the principles of rustic architecture? How did the buildings at Camp Misty Mount meet these guidelines?

- Since all the lumber used for the project was harvested locally, what can you determine about the variety of types of trees that were growing in the forest? Name two species that were harvested.

- Why was the use of logs as opposed to sawn lumber a sound economic practice? How did the use of logs contribute to the efficiency of the operation? How do you think the removal of standing dead trees for logs might speed the regrowth of the forest?

Adapted from Sara Amy Leach, "Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Architecture at Catoctin Mountain Park" (Frederick County, Maryland) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988; Sara Amy Leach, "Camp Misty Mount Historic District" (Frederick County, Maryland) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988; and documents from park files.

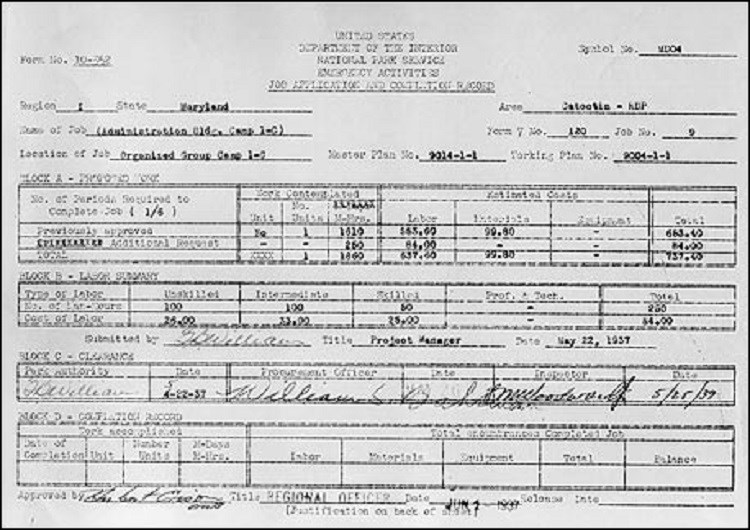

Determining the Facts:

Document 1: Job Application and Completion Record

(Transcript of job appliation, pictured below):

This record is a form that was completed by filling in tables. An outline of the information was created to make it easier for reading purposes.

Form No. 10-352

Symbol No. MD04

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES

JOB APPLICATION AND COMPLETION RECORD

Region: I

State: Maryland

Area: Catoctin - RDP

Name of Job: (Administration Bldg. Camp 1-C)

Form 7 No. 120

Job No. 9

Location of Job: Organized Group Camp 1-C

Master Plan No. 9014-1-1

Working Plan No. 9004-1-1

I. BLOCK A - PROPOSED WORK

No. of Periods Required to Complete Job (1/6)

A. Previously approved:

1. Work Contemplated

a.Unit: No

b. No. Units: 1

c. M-Hrs.: 1610 [M-Days was printed on form, but crossed out]

2. Estimated Costs

a. Labor: 553.60

b. Materials: 99.80

c. Equipment: -

3. Total=653.40

B. Additional Request:

1. Work Contemplated

a. Unit: -

b. No. Units: -

c. M-Hrs.: 250 [M-Days was printed on form, but crossed out]

2. Estimated Costs

a. Labor: 84.00

b. Materials: -

c. Equipment: -

3. Total=84.00

C. Total:

1. Work Contemplated

a. Unit: XXXX

b. No. Units: 1

c. M-Hrs.: 1860 [M-Days was printed on form, but crossed out]

2. Estimated Costs

a. Labor: 637.60

b. Materials: 99.80

c. Equipment: -

3. Total=737.40

II. BLOCK B -- LABOR SUMMARY

A. No. of Man-Hours

1. Type of Labor--Unskilled: 100

2. Type of Labor--Intermediate: 100

3. Type of Labor--Skilled: 50

4. Type of Labor--Prof. & Tech: -

5. No. of Man-Hours Total=250

B. Cost of Labor

1. Type of Labor--Unskilled: 26.00

2. Type of Labor--Intermediate: 33.00

3. Type of Labor--Skilled: 25.00

4. Type of Labor--Prof. & Tech: -

5. Cost of Labor Total= 84.00

Submitted by: S. B. Williams [signature]

Title: Project Manager

Date: May 22, 1937

III. BLOCK C -- CLEARANCE

A. Park Authority: S. B. Williams [signature]

B. Date: 5-22-37 [4 (April) was written as the month, but crossed out and 5 was added]

C. Procurement Officer: Williams, S. B. [signature]

D. Date: [not legible]

E. Inspector: [signature not legible]

F. Date: 5/25/37

IV. BLOCK D -- COMPLETION RECORD

[Block D was not filled out on this form. Following was the requested information.]

A. Work Accomplished

1. Date of Completion

2. Unit

3. Number Units

4. M-Days/M-Hrs

B. Total encumbrances Completed Job

1. Labor

2. Materials

3. Equipment

4. Total

5. Balance

Approved by: [signature not legible]

Title: Regional Officer

Date: June [?] 1937

Release Date: [blank]

(Justification on back of sheet)

This record provided an estimation of labor and materials required for the construction of specific buildings within the camp. Data from this form provided an accurate accounting of man-hours and funds expended on the project.

Questions for Document 1

- What building does the job application pertain to?

- What is being requested in the application?

- Workers were contracted for six months. This was considered a "period." How many months did it take to complete the Administration Building?

- What was the cost of materials for the Administration Building? The labor cost? What percentage of the cost of construction was for materials? for labor?

- How much did skilled, intermediate, and unskilled laborers make per hour? If the unskilled workers were earning today’s minimum wage, how much would the intermediate and skilled workers make if they earned amounts proportionate to the salaries earned in the 1930s?

- Organized groups paid $.25 per camper per night to rent Camp Misty Mount. How long would an unskilled worker have to work in order to pay for a five-night stay? If that worker was paid today’s minimum wage and had to work the same amount of time to pay for lodging, how much would it cost per camper per night? The actual fee for a four-person cabin in 1999 was $40.00 per night. Was the camp more or less affordable in the 1930s?

Visual Evidence:

Photo 1: Children from the Baltimore League for Crippled Children gather outside a cabin, 1937.

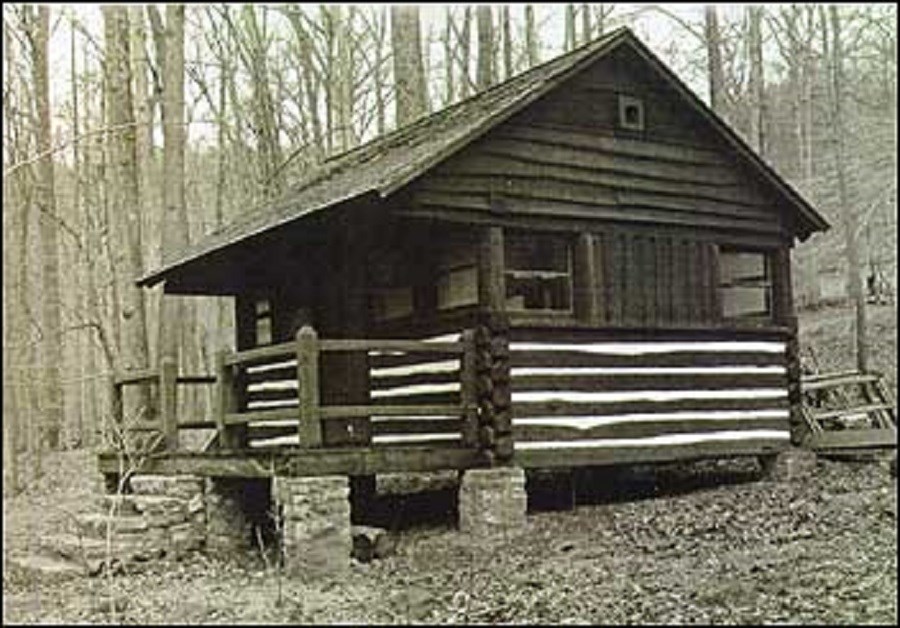

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

- How would you describe each of the cabins? What are some of the similarities and differences between them?

- Why do these buildings blend harmoniously with the landscape? Would the appearance of the camp be changed if sawn lumber had been used exclusively?

- The Baltimore League for Crippled Children was the first group to use Camp Misty Mount. Do you think these buildings would be considered accessible for the disabled by today's standards? What, if any, alterations do you think would have to be made to accommodate the mobility-impaired?

Visual Evidence

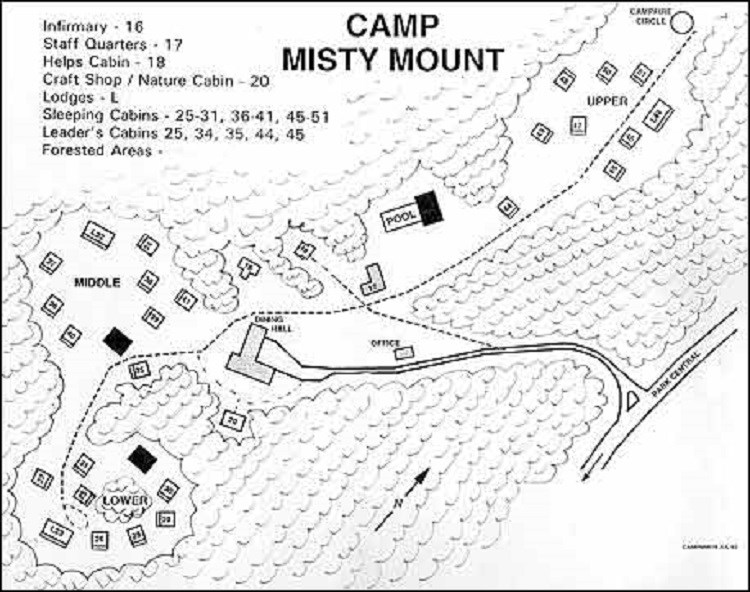

Drawing 1: Plan of Camp Misty Mount

Questions for Drawing 1

- Why do you think that some of the buildings were clustered? What buildings are in the three clusters?

- Why do you think the swimming pool, craft shop/nature cabin, and the campfire ring are located away from the sleeping cabins?

- Both the swimming pool and the middle unit restroom are considered non-historic structures according to the standards of the National Register of Historic Places. The swimming pool was completely remodeled and the restroom rebuilt, and so neither looks the same as it did in the 1930s and 1940s. All the other buildings in the camp do meet the National Register requirements, and are therefore regarded as "contributing" to the historic significance and character of the camp. Do you think it is important that historic areas (called "districts" by the National Register) make it clear to visitors which buildings, structures, and other features are old and which are more recent? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence:

Photo 3: View of the forest in the 1930s.

Photo 4: View of the forest in the early 1970s.

Questions for Photos 3 & 4

- Compare Photos 3 and 4. What is different about the type and amount of vegetation? Do there appear to have been greater numbers of trees in the 1930s or in the early 1970s?

- How do you think the animal population on Catoctin Mountain might have changed over the same period?

- What do you think the area might look like today?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students learn more about Depression-era relief programs as well as discover the history of protected natural resources in their area.

Activity 1: Determining the Success of Jobs Programs

One of the goals of the Recreational Demonstration Area was to ease unemployment caused by the Depression. Have the students use editions of local newspapers (usually available on microfilm in the public library) to determine the economic conditions in their community during the Depression. Then ask a local historian or knowledgeable public official to speak to the class and describe the federal or state job programs that existed in their community or state during the Depression.

Next, have students contact the local Chamber of Commerce to identify the major industries and employers in the area today. Have students discuss what could happen if all of the workers in one or several of these industries or businesses were suddenly unemployed. What would be the short- and long-term effects? Finally, have students work in groups to devise a jobs program that would provide short-term employment and would have long-term benefit for the community. Have students share their ideas and compare them with the WPA and the CCC jobs programs at Camp Misty Mount in the 1930s.

Activity 2: Providing Outdoor Opportunities

Explain to students that during the 1930s, organization camps were seen as the most effective means of helping urban populations obtain an experience in nature. Break students into groups of three to four, and tell them they have just become counselors at a facility like Camp Misty Mount. Their job is to organize a one-week outdoor education program for students their age. Their plans should run Monday through Friday and mix recreation and environmental education. What should the students they will be working with learn, and why? What will the daily schedule be? Are there any facilities they would like to add to Drawing 1 to make this week more enjoyable? Have the groups reassemble and discuss their plans. Conclude by asking them if they think such programs are important, and why they have reached that conclusion.

Activity 3: Recreation and Conservation

The RDAs chose submarginal land for recreational areas to prove that proper conservation would allow forests and fields to recover from human misuse. Have students work in small groups to locate state or federally protected forests or other natural places in their immediate area. Have them find out the current ownership and history of the sites and explain why they are publicly or privately owned. If possible they should look for maps of their locality from 10, 25, and 50 years ago, and note how much natural land was undeveloped compared with today. They might use field guides to determine how long various places have been left to nature or whether they have been part of a reclamation project. Then have students analyze the current conditions of the properties, the growth of surrounding communities, the availability of recreational areas, and the importance of the ecosystem to decide if these areas should be preserved. Have each group present its findings to the class and then hold a general discussion about the quality of the remaining natural places in their locality. If appropriate, have the students write letters to public officials commending specific environmental contributions, or appealing for the conservation or reclamation of additional areas.

Camp Misty Mount: A Place for Regrowth--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Camp Misty Mount: A Place for Regrowth, students can more easily appreciate a successful WPA project that continues to meet the recreational needs of individuals and organized groups and has helped the forest to regrow.

National Park Service

-

Catoctin Mountain Park is a unit of the National Park System. The park's Web site details the history of the park and visitation information. Included on the site are features on the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, such retreats as Camp David and Camp Misty Mount, and the role of the charcoal/iron industries in the Catoctin Mountain Park.

The New Deal: Library of Congress

- Search the American Memory Historical Collection of the Library of Congress for further documentation on the New Deal and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Included on the site are photographs from the Great Depression, manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, numerous documents and photographs of WPA workers and their projects, and much more.

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

- The NARA's Herbert Hoover: Presidential Library and Museum offers a brief history of how the Great Depression came about including Herbert Hoover's role as President during this tumultuous time.

-

The NARA's feature, A New Deal for the Arts, demonstrates one successful aspect of President Roosevelt's New Deal agenda created to alleviate the consequences of the Great Depression.

-

The NARA is an incredible resource for records of the Work Projects Administration. Search their guide to Federal Records to find what sources are available for public research.

Tags

- new deal

- catoctin

- catoctin recreational demonstration area

- maryland

- maryland history

- recreational demonstration area

- recreational demonstration areas

- franklin delano roosevelt

- great depression

- camp misty mount

- camp mist mount a place for regrowth

- back-to-nature movement

- labor history

- outdoor education

- education

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- conservation

- art and education

- early 20th century

- conservation and recreation

- twhplp