Last updated: July 25, 2019

Article

Cape Krusenstern National Monument Wilderness Character Narrative

Bordered by the Chukchi Sea to the west, Kotzebue Sound to the south, and the wild and scenic Noatak River to the east, Cape Krusenstern National Monument (Cape Krusenstern) feels like a window into the past. While wooly mammoths only exist in the fossil record here, musk oxen still claim their place among the sweeping valleys and thick carpets of tundra. Beach ridges, formed by the slow accretion of sediment along the coast, bear the evidence of over 4,000 years of human occupation, a tradition which continues with the subsistence users of the present. Subject to the extremes of the Arctic weather, life in the monument requires specialized skills and adaption as cold winds howl through the darkness of winter and ice chokes the coast.

Exposed as it is to the constant battering of the wind and sea, Cape Krusenstern is nonetheless a haven for plants and wildlife that have learned to thrive during the vibrant summers. Migratory birds and waterfowl take advantage of protected coastal lagoons to feed and raise young. Small, hardy alpine plants bloom in a rainbow of colors along the Igichuk and Mulgrave Hills, and a wealth of berries emerge as caribou migrate from summer feeding grounds to fall breeding grounds. The connection with the sea is not far away, with populations of fish and marine mammals an important link in the ecosystem.

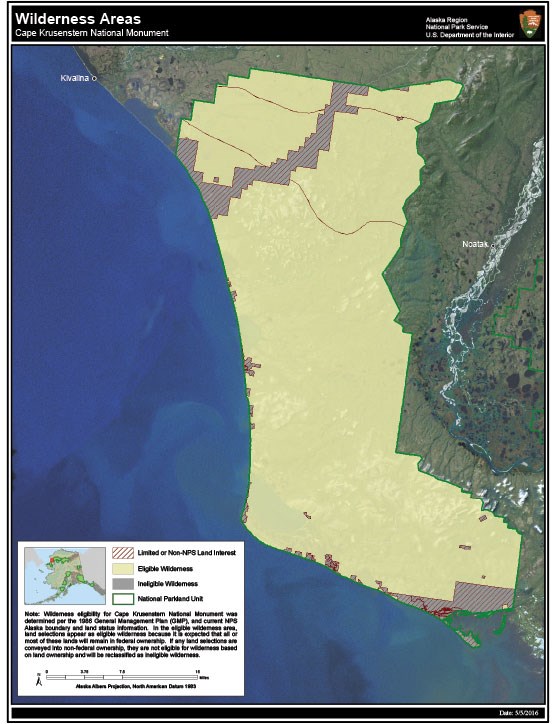

This area is home to more than just flora and fauna. Iñupiaq have inhabited and used this living cultural landscape for generations, as evidenced by the archeological record. The continued subsistence use of both marine and terrestrial resources is an important component, and a founding purpose of the monument. Additionally, Cape Krusenstern contains almost 597,000 acres of eligible wilderness, managed in accordance with NPS policy as wilderness in order to preserve its wilderness character. While it is just west of the larger, contiguous wilderness areas of the Noatak, Kobuk, Gates of the Arctic, and Selawik, it is an island unto itself with a unique set of threats and management challenges.

Climate change is the most imminent threat across the Arctic, and with it comes the potential for a northern shipping route which could have serious impacts on the marine ecosystem and subsistence resources of Cape Krusenstern. A road delivering the products of resource extraction to a coastal shipping port has already bisected the monument, and the possibility of further regional developments could make preservation challenging. However, these same developments provide jobs and resources for the region, which in turn enable residents to continue to pursue subsistence lifestyles. This complicated web requires managers to be flexible, creative, and practical. Effective stewardship necessitates cooperation and coordination between land managers and local users to find meaningful protection of both wilderness values and the Iñupiaq way of life.

The remoteness and inaccessibility of Cape Krusenstern have protected it from much modern human intervention. Vast swaths of tundra exist with little manipulation, and the wildlife is free to disperse of their own accord. Rivers and streams meander unhindered through the hills and out to the coastal lagoons before flowing to the sea. The processes of beach erosion and accretion continue without human controls such as seawalls and jetties; the force of the ocean is absorbed directly by this wild coastline. Fire is not a large component of the ecosystem due to its maritime climate, but the majority of the monument is managed to allow naturally ignited fires to burn, only requiring active protection for a handful of locations and private inholdings.

Some of the boundaries do not follow topographic features, but one would currently be hard-pressed to identify where the monument ends and other lands begin. The landscape maintains a continuity that is mostly unaffected by surrounding development. People and animals are free to roam unimpeded by fences or barriers.

There are several potential threats to the untrammeled character of Cape Krusenstern. Negative interactions between wildlife and private inholdings could lead monument staff to haze or destroy musk oxen and brown bears, if other alternatives do not prove successful. As climate change continues, there may be an increase in requests for manipulative scientific research such as wildlife collaring projects. Cape Krusenstern is fairly well insulated from the actions of modern human management, but it is not impervious and care must be taken to use restraint and humility when evaluating options.

The ecosystem of Cape Krusenstern contains a subtle beauty. A short, frenzied growing season punctuates the long, deep quiet of winter. Underlain by permafrost, the landscape consists of ancient glacial moraines and limestone hills that are blanketed in the miniature detail of the lichens and flowers of the tundra. The beach ridges that attest to the long history of human occupation also contain 5,000 years of environmental history, recording storminess, erosion, accretion, and ocean currents.

This is a landscape that can be both harsh and nurturing, providing food and breeding grounds as well as screaming winds and piercing cold. Different types of berries provide much needed forage before winter, including blueberries, cloudberries, crowberries, and cranberries. The glimpse of fall is greeted with an incredible splash of color from foliage of all types, and the darkness of winter provides a backdrop for the swirl of northern lights.

Many creatures find a home in Cape Krusenstern year-round, but summer teems with activity. Waterfowl, shorebirds, migratory birds and raptors breed and raise young. This includes ducks, loons, terns, gulls, plovers, Sandhill cranes, jaegers, short-eared owls, and the rare sightings of Kittlitz’s murrelets, gyr falcons, peregrine falcons, or rough-legged hawks. Inland from the coast, willow ptarmigan lie camouflaged, exploding from the brush in a flash of white wings when startled. Caribou flow across the landscape, sometimes accompanied by brown bears, wolves, and red and arctic foxes. With some luck, there is a sighting of a wolverine, Dall sheep, or moose. A recent returnee to the hills is the musk ox, present since the Pleistocene, extirpated in the late 1800s, and reintroduced to the area in the 1970s. Their qiviut, the extraordinarily light and insulating underwool, sheds naturally each year and drapes the bushes like gossamer.

Off the coast, marine mammals play an equally important role in the ecosystem. Seals, beluga whales, and walruses are not far away, and polar bears occasionally wander through. An abundance of fish occupies the ocean, rivers, and coastal lagoons including salmon, pike, whitefish, Arctic char, and Dolly Varden. Fish are an important food source for many of the birds who reside in and migrate to the monument, and the carcasses of marine mammals are a welcome find for scavengers.

This Arctic ecosystem is delicate, and it is hardly isolated from the rest of the circumpolar north. Climate change is a looming challenge as storm cycles flux, shrubs overtake tundra, and the hard grip of winter shortens and lessens. Later freeze up and earlier breakup of the sea ice have already begun to change the dynamics of the ecosystem, and contributes to the potential use of a new northern shipping route which could have serious impacts on the aquatic environment. Marine debris from around the world finds its way to Cape Krusenstern’s beaches, and pollution or spills in the ocean would quickly arrive onshore. In a place where living things need to be highly specialized to survive, there is not much room for invasive or non-native species. None have been documented yet, but known invasive species reside on nearby airstrips, waiting to hitch a ride.

Cape Krusenstern is crossed by a single road in the northern part of the monument, contained entirely on land owned by the native-owned corporation NANA Regional Corporation, Inc. (NANA Corporation). This road leads to a shallow sea port, also built on NANA Corporation land, connecting the mining operations of the Red Dog Mine with the sea. While this development is not on monument land, it restricts the free flow of plants and animals between the northern and southern sections of Cape Krusenstern. Some caribou have been shown to shy away from the road – many cross it, some just take longer to cross, but some avoid it altogether, choosing to trek completely around or overwinter in different areas. Considerable fugitive dust is produced by the mine, road, and port site, which contributes to the bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the surrounding ecosystem. The levels of metal in mosses and lichens are worrisome for the long term viability of natural habitats and subsistence resources.

All-terrain vehicles (ATVs) are commonly used for subsistence and administrative use, but can affect the natural quality. Some trails have been unofficially identified as historic travel corridors, but no official ATV trails have been designated and off-trail riding can have a long-lasting impact on the land. A more localized problem is the interaction between musk oxen, brown bears, and private inholders in the monument. These animals are known to break into and severely damage camps, knock over grave stones, and injure or kill dogs.

Animals can be killed in defense of life or property, and the occurrence of this could increase depending on animal populations, their level of habituation around humans, and cultural attitudes. Outside the monument boundary to the northwest, erosion control in the coastal village of Kivalina could limit accretion on Cape Krusenstern’s beaches by preventing sediment transportation farther down the coastline.

The imprint of modern human development is largely absent on this vast and primitive landscape. There are few amenities, structures, or other permanent installations. The exceptions are fairly subtle, and generally in place for safety in this harsh and sparsely populated area. The Anigaaq ranger station is one such example, built shortly after the

monument’s establishment. Two temporary shelters are maintained along the coast for the safety of winter travelers. Temporary trail markers guide winter travelers from Kotzebue in the south to the village of Kivalina in the north.

Reminders of modern development do occur in the monument. Some scientific installations are present, including two permanent weather stations, many small, above-ground vegetation plot markers, and usually a handful of temporary installations depending on approved projects. A defunct radio tower stands atop Mt. Noak, the tallest mountain in the monument at 2,010 feet (613 meters). Removal of non-operational infrastructure such as this would improve wilderness character. An airstrip and the ghost of a road are all that is left of a military radio tower and small development in the Kakagrak Hills, on what is locally known as Radio Hill. It has become a destination for the limited summer commercial recreational use due to the availability of the airstrip and its easy access to good hiking in the hills.

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (ANILCA) allows the use of airplanes, motorboats, ATVs, and snowmachines in Alaskan wilderness. Still, these uses impact the undeveloped quality of Cape Krusenstern. Because access to the monument is difficult, most users including staff, researchers, subsistence users, and visitors use motorized means. Motorboat travel is usually confined to the coastal lagoons where subsistence users access areas for berry picking or collecting gull eggs, and researchers seine for fish. Plane access is very common, mostly by float plane on the lagoons or river mouths but also by wheeled plane on the beaches or airstrips. Helicopters are used infrequently for administrative and research purposes.

ATVs are generally used on the beaches to access inholdings, seasonal camps, or research sites, but divert inland around certain obstacles like Battle Rock or for access to good berry patches. ATVs are occasionally used to access the monument illegally via the Red Dog Mine road, which is not open to the public. In the winter, snowmachines are focused on two trails – one coming up the coast and one on the east boundary – but are used for hunting across the entire monument. There is the potential to formalize these commonly used ATV and snowmachine trails, which could include installing permanent trail markers. Additionally, research in the monument could increase, bringing an increase in requests for motorized uses and temporary or permanent installations.

Technology is ever improving and more advanced motorized access could alter travel patterns in the region. This is particularly important as most subsistence users live in villages surrounding Cape Krusenstern, specifically Kivalina to the north, Noatak to the east, and Kotzebue to the south. Noatak is essentially surrounded by parklands, making it especially difficult to deliver supplies. One suggestion to alleviate this issue is to haul fuel using a winter corridor from the Red Dog Mine port site across the monument to the village. A proposal like this highlights the tough questions that must be discussed fully by managers

Cape Krusenstern provides significant opportunities for solitude, punctuated by the small chance to cross paths with local users, administrative staff, researchers, or other visitors. The odds of these interactions are low, concentrated along the coastline, and are usually positive. Coming across subsistence users gathering or processing local resources offers an opportunity to appreciate a different connection to the landscape, and to begin to understand the depth of human history that is woven into the land. While summer seems like a more conducive time to visit with long hours of daylight and warmer weather, winter offers the unique solitude of a hibernating landscape.

The general lack of recreational users means that recreation is largely unlimited and unconfined. No permits are required, there are no trails, campsites, or other amenities, and there are few restrictions on visitor behavior. It is relatively close to Kotzebue, the largest transportation hub in the area, but it is still difficult to access for those outside the region due to its remoteness and isolation. There are few commercial use operators, so visitors have to be fairly independent and selfsufficient.

Summer provides opportunities for hiking, canoeing, kayaking, birdwatching, and photography, with access by motorboat or float plane. Winter usually offers more access, since snowmachines can easily travel across the sea ice from Kotzebue. Dog mushing persists, a tribute to an older form of transportation, with several long and short-distance racing mushers residing in the Kotzebue area and some sprint and mid-distance races still being held.

While the monument is removed from many of the sights and sounds of development, there are a few key exceptions. The Red Dog Mine, access road, and shallow sea port are all readily visible from inside large portions of the monument. The sound of mining echoes across the hills, vehicle traffic and dust are prominent, and the patriotically painted storage facilities at the port site can be seen for miles. Air traffic between Kotzebue and surrounding villages, as well as other motorized noise from ATV, motorboat, or snowmachine use, is a reminder of modern human dependence on motors.

People have been deeply connected to and a part of this ecosystem for thousands of years, and a unique and important archeological story is encompassed by Cape Krusenstern. More than 400 sites have been found and documented, with the oldest ones dating back over 10,000 years. This prehistoric record illustrates a history of multiple occupations over thousands of years, including the development of an Arctic maritime economy that continues with the Iñupiaq and Yu’pik today. The monument was part of Beringia, a vast area connected to Asia during the ice age. These sites are a chapter in the larger story of the peopling of the Americas, including additional migrations from Asia, and preserve evidence of the homeland for the first Americans.

Most archeological sites are located on beach ridges along the southwest coast. The beach ridges were formed by erosion and accretion, preserving a record of storminess and coastal currents dating back about 5,000 years to when the local sea level stabilized. They also preserve the record of over 4,000 years of human occupation, ranging from summer seasonal camps to year-round residences. These are some of the oldest coastal occupations in North America, and include hearths, houses, cache pits, and surface scatters. One of these sites is a famous archeological anomaly – different from other sites in Cape Krusenstern, and the only known site of its kind in Alaska. Around 3,000 years old, this site includes winter and summer settlements, and preserves evidence of what is known as the Old Whaling culture. The details of these unique and intriguing whale hunters are still elusive, but the clues remain protected within the monument boundaries. While climate change is impacting some of the newer, coastal sites through erosion and deposition, older sites are less affected. Some of the most significant damage has actually been from previous archeological excavations. Current cultural resource projects focus on minimal site disturbance and good documentation for future monitoring.

Part of a different chapter of the past, there are two cabins in the monument that are historic, and potentially eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. One is the Tukrok Shelter Cabin, built around 1925, and the other is the Aitiligauraq Shelter Cabin, built a little later. Both were constructed by the Alaska Road Commission to support the mail and supply route between Kotzebue and Point Barrow. The emergence of airplanes eventually replaced dog teams, but the cabins remain as a testament to this period in history. Today the cabins have deteriorated, with no current plans to actively preserve or reconstruct them.

populations. The importance of the monument to the local culture cannot be understated – it is their backyard, their neighbors’ backyard, their home. For generations, Iñupiaq have lived in the area and relied upon the resources provided by the land and sea. Until recently, families lived there year-round like their ancestors, spending summers at camps on the coast and winters farther inland at cabins among the few pockets of trees. Relatively few people spend time at camps throughout the year now, but many people have strong emotional connections and continue to spend the majority of the summer season at camps on private inholdings, particularly around Sisualik on the southern tip of the monument. This strong sense of identity, both personally and as a community, connects people to a traditional way of life that spans multiple generations.

The monument provides a wide variety of resources to those who acquire the knowledge to use them, including the take of caribou, moose, musk oxen, wolves, foxes, bears, waterfowl, and marine mammals such as seals, beluga whales, and walrus. These marine mammals and many species of fish are processed onshore at camps, and racks of filleted and drying fish are common along the beaches. Notably, the same accretion process that contributes to the beach ridges also seasonally closes the mouth of the Tukrok River at Anigaaq. This provides a unique opportunity for subsistence users to dig trenches in late fall, letting the water run out and trapping fish such as least ciscoes and whitefish that have been fattening all summer in the lagoon waterways. Local residents harvest gull eggs in the spring, and late summer brings a bounty of berries such as blueberry, cranberry, and aqpik (cloudberry). Other plants are harvested for food and medicinal purposes.

The beauty of this protected environment lies in its ability to sustain the local culture, since the preservation of habitat increases the resilience of both the ecosystem and the people that depend on it. Just as the removal of an animal species would be detrimental, so would the removal of the people. This way of life and the traditions that are so intimately connected to the area are as vulnerable as the land itself; the same threats that imperil the ecosystem also tug at the threads holding together this culture. Global warming is one of the most pressing issues, changing what has been considered normal and undermining generations of knowledge. Sea ice is less predictable, which impinges on hunting and winter travel. The changing movements and distribution of animals affects hunting, trapping, and fishing. Development pressure and modernization are constantly challenging how people balance personal and community priorities. Camps that have been on private inholdings for generations are slowly coming up for sale – these are usually purchased by the NPS so that the land can continue to be in the public trust, but this also represents a growing dependence on a cash economy. Younger generations are challenged to live with one foot in two worlds.

Managers must also straddle two worlds, as the challenge of managing this area for subsistence and wilderness brings together potentially conflicting philosophical backgrounds and priorities. The very thing that makes the monument unique – the past and present human use –seems to run contrary to the Wilderness Act’s statement that “man is a visitor who does not remain.” However, wilderness and subsistence are highly complementary as evidenced by further reading of the Wilderness Act and the additional legislation of ANILCA. Protecting wilderness protects subsistence lifestyles, and underlying the two are the same respect for the land, interconnectedness, and spiritual resonance. Focusing on their common goals can help to preserve the aspects that are essential to both wilderness and subsistence to ensure that these important resources persist for future generations.