In 2015, 289 sea turtle nests (277 loggerhead, 10 green, and 2 Hawksbill nests) and 242 false crawls were documented at Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The first nesting activity was documented on May 13 and the last nesting activity was documented on September 4. Mean hatch success for all nests was 56.8% while mean emergence success was 48.8%. A total of 286 stranded sea turtles were documented within the seashore in 2015.

National Park Service

Introduction

Five species of sea turtles can be found in Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CAHA)—the loggerhead (Caretta caretta), green (Chelonia mydas), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), and Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii). In the 1970’s, the Leatherback, Kemp’s Ridley, and Hawksbill were listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) as endangered and the Loggerhead as threatened. The Green population that nests in the Northwest Atlantic was listed on July 28, 1978, and is designated as threatened.

Non-breeding sea turtles of all five species can be found in the near-shore waters during much of the year (Epperly 1995). Cape Hatteras lies near the extreme northern limit of the nesting range for four of the five sea turtle species, including the Loggerhead, Green, Kemp’s Ridley and Leatherback. Hawksbill sea turtles, in the past, were not known to nest at CAHA, but are known to occur here through strandings. This year CAHA documented its first two Hawksbill sea turtle nests through DNA analysis of a single egg taken from each nest. The occasional Kemp’s Ridley nest has been documented in North Carolina over the past five years and in 2011 CAHA documented its first Kemp’s Ridley nest.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore has been monitoring sea turtle activity since 1987, and standard operating procedures have been developed during this time. This report summarizes the monitoring results for 2015, comparisons to results from previous years, and the resource management activities undertaken for turtles in 2015. Cape Hatteras National Seashore follows management guidelines defined by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) in the Handbook for Sea Turtle Volunteers in North Carolina, species recovery plans, and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation (ORVMP).

ORV Management Plan

On February 15, 2012 the ORVMP was enacted at CAHA. It was developed from 2007-2012 and included a special regulation detailing requirements for off- road vehicle (ORV) use at CAHA. A copy of the ORV Management Plan and other related documents are available electronically at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/caha. It includes establishment of an ORV permit system to drive on CAHA beaches. It also establishes survey times, frequency and buffer requirements for sea turtle nests and hatchlings. This was the fourth year the ORV Management Plan guided the management of protected species, including sea turtles, at CAHA.

The National Park Service (NPS) modified wildlife protection buffers established under the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Final ORVMP and Environmental Impact Statement of 2010 (ORV FEIS). This proposed action results from a review of the buffers, as mandated by Section 3057 of the Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2015, Public Law 113-291 (2014 Act). The 2014 Act directs the NPS "to ensure that the buffers are of the shortest duration and cover the smallest area necessary to protect a species, as determined in accordance with peer-reviewed scientific data." *pulled from https://parkplanning.nps.gov/document.cfm?parkID=358&projectID=56762&documentID=65752

The Record of Decision indicates that CAHA will "conduct a systematic review of data, annual reports, and other information every 5 years, after a major hurricane, or if necessitated by a significant change in protected species status (e.g. listing or de-listing), in order to evaluate the effectiveness of management actions in making progress toward the accomplishment of stated objectives". As part of the Reporting Requirements of the Biological Opinion (BO) for the ORVMP (November 15, 2010), "an annual report detailing the monitoring and survey data collected during the preceding breeding season (as described in alternative F, in addition to the additional information required in the …Terms and Conditions) and summarizing all Piping Plover, Seabeach Amaranth, and sea turtle data must be provided to the Raleigh Field Office by January 31 of each year for review and comment".

In the November 15, 2010 BO, the USFWS determined that the level of anticipated take is not likely to result in jeopardy to the loggerhead, green, or leatherback sea turtle species. Through the actions taken by the resource management staff, CAHA has complied with the reasonable and prudent measures that are necessary and appropriate to minimize the take of sea turtles. Protection was provided to sea turtles that came ashore to nest, incubating nests were monitored and protected, and emerging hatchlings were provided protection from ORVs. Proposed activities and access to nesting sea turtles, incubating turtle nests, and hatching events were timed and conducted to minimize impacts on sea turtles and sea turtle productivity. Resource management staff also responded to stranded sea turtles and coordinated the transport and delivery of live strandings to appropriate rehabilitation facilities. The non-discretionary terms and conditions for sea turtles were also met by providing the USFWS with this annual report. This annual report summarizing monitoring efforts and data collected during the 2015 breeding season and aids in fulfilling the reporting requirements of the November 15, 2010, BO.

Cooperating Agencies

CAHA cooperates with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and NCWRC on sea turtle protection. All nesting activity and stranding reports are reported to the North Carolina Sea Turtle Program Coordinator at NCWRC through the seaturtle.org website. An annual permit is issued to CAHA by NCWRC under the authority of the USFWS for the possession and disposition of stranded marine turtles and relocation of nests.

Methods

Nesting Activity

Monitoring for sea turtle nesting activity began on April 30, 2015. Patrols utilizing UTVs (or 4X4s during inclement weather) were conducted in the morning, beginning approximately at dawn. Each nesting activity was recorded as either a false crawl or nest. All nests were confirmed by locating eggs at the nest site. One egg was taken from each clutch for research purposes. The decision to relocate the nest or for the nest to remain in situ was made at the time of nest discovery. If no eggs were laid, the nesting activity was considered a false crawl and recorded by collecting a GPS point at the apex of the crawl. All sea turtle “activities” were reported to NCWRC using the Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System (STNMS) through the Seaturtle.org website.

All nests were protected from human disturbance by installing a 10 x 10 meter signed area around the nest site. At day 50 – 55 of incubation, a closure beginning approximately 5 meters behind the nest and extending to the water line, with a width of 30 meters was installed (These buffer requirement are a result from a review of the buffers, as mandated by Section 3057 of the Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2015, Public Law 113-291 (2014 Act). The 2014 Act directs the NPS "to ensure that the buffers are of the shortest duration and cover the smallest area necessary to protect a species, as determined in accordance with peer-reviewed scientific data.” This closure protected the nest site and hatchlings from human disturbance during hatching events. Each nest site was checked daily in order to document any disturbances or hatching events.

Approximately 3 − 5 days after an initial hatching event, nests were excavated and closures were removed. Resource management staff collected required data to determine hatch and emergence success for each nest excavation. Live hatchlings discovered upon excavation of the nest were collected and released at or after dusk the same day. Monitoring efforts to locate new nests ended Sept 30, 2015.

Stranding Activity

A stranded turtle is a non-nesting turtle that comes to shore either sick, injured, or dead. Data was collected for each reported or observed stranding. Whenever possible, further data was collected by performing a necropsy on dead strandings. Live stranded turtles were transported to a facility for treatment and recovery. All data was reported to NCWRC using the Sea Turtle Rehabilitation and Necropsy Database (STRAND) through the seaturtle.org website.

An increased effort to locate stranded turtles began in early November and continued throughout the winter due to the increased chance of “cold stunned” turtles. Searches for cold stunned turtles emphasized CAHA’s sound side shorelines where the majority of cold stunned turtles have been found in the past. Cold stunning refers to the hypothermic reaction that occurs when sea turtles are exposed to prolonged cold water temperatures. Initial symptoms include a decreased heart rate, decreased circulation, and lethargy followed by shock, pneumonia and possibly death (from http://www.nero.noaa.gov/prot_res/stranding/cold.html).

Results

Nesting

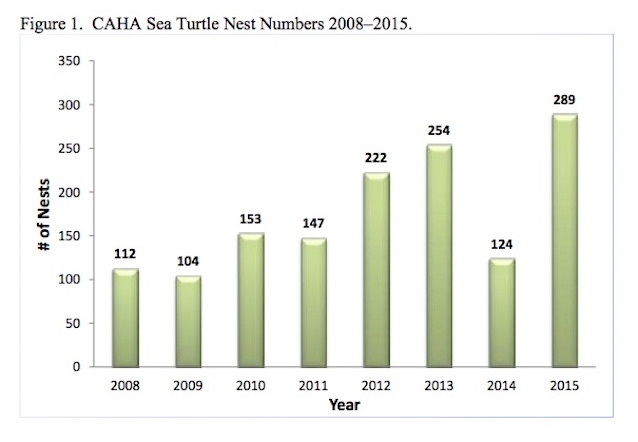

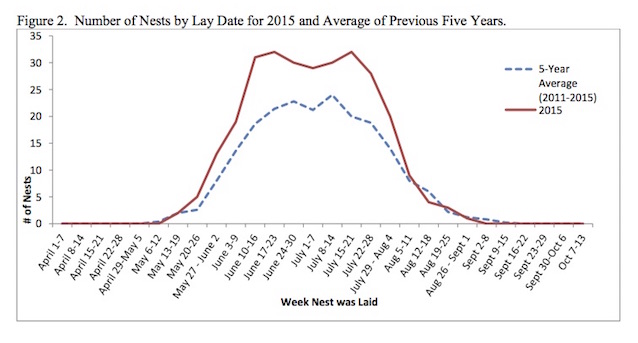

A total of 289 nests (277 loggerhead, 10 green, and 2 hawksbill nests) were observed at CAHA in 2015. Of the confirmed nests, 5 (1.7%) were found on Bodie Island, 199 (68.9%) on Hatteras Island, and 85 (29.4%) on Ocracoke Island (Appendix B, Maps 1 – 6). This was the greatest number of nests recorded at CAHA in a single nesting season (Figure 1) since monitoring has occurred on the seashore. The first recorded nest for the 2015 season occurred on May 13 and the last nest was recorded on September 4. While nesting occurred throughout this period, peak nesting occurred from June 17 to July 21. (Figure 2).

Nest Relocation

Of the 289 nests, 56 (19.3%) were relocated (Appendix A). Most nests were moved due to natural factors including location of nest at or below high tide line or the nest was laid in an area susceptible to erosion, etc. Relocation methods recommended by NCWRC, found in the Handbook for Sea Turtle Volunteers in North Carolina (2006), were followed.

False Crawls

During the 2015 breeding season, 242 false crawls or aborted nesting attempts were recorded. False crawls accounted for 45.6% of the 531 total turtle activities. Of the 242 false crawls, 4 (1.7%) was documented on Bodie Island, 165 (68.2%) on Hatteras Island, and 73 (30.1%) on Ocracoke Island (Appendix B, Maps 7 – 12). There were 3 documented green, and 1 documented Kemp’s Ridley, and 238 documented loggerhead sea turtle false crawls.

Hatching

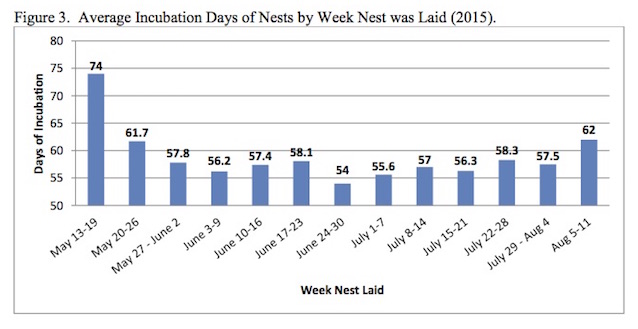

In 2015, the mean clutch count was 116.5 eggs per nest (Table 1 and Appendix A). The mean clutch count was determined using total egg counts at the time of relocation from relocated nests only. Average incubation period of nests with known lay and emergence dates was 56.9 days (Table 1 and Appendix A). Incubation periods depend mostly upon sand temperature (Bustard and Greenham 1968) and ranged from 54 days to 74 days (Figure 3). Some emergences went undetected due to rain, wind, tides and storm events.

Table 1. Sea turtle hatch summary 2008-2014.

|

Year |

Nests |

Avg. Clutch |

Average Incubation (days) |

Total Eggs |

# Emerged |

EMR% |

|

2008 |

112 |

109.0 |

59.7 |

11573 |

5965 |

52% |

|

2009 |

104 |

114.9 |

65 |

11121 |

3430 |

31% |

|

2010 |

152 |

110.9 |

57 |

16300 |

7843 |

48% |

|

2011 |

147 |

115.8 |

58 |

13661 |

6483 |

48% |

|

2012 |

222 |

105.3 |

60.1 |

24107 |

17965 |

73% |

|

2013 |

254 |

116.9 |

62.3 |

28863 |

16860 |

56% |

|

2014 |

124 |

105.3 |

62.2 |

12474 |

6172 |

45% |

|

2015 |

289 |

116.5 |

56.9 |

30168 |

15960 |

49% |

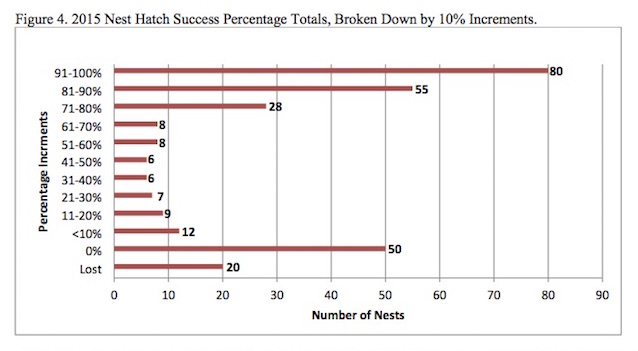

Mean emergence success was calculated by taking the unweighted mean of all the individual nest emergence successes. Emergence success is the total number of hatchlings that emerged unaided from the nest cavity, relative to the total number of eggs in the nest. Any hatchlings found during excavations were not considered to have emerged. Mean emergence success for 2015 was 48.8% (Appendix A). Mean hatch success was calculated by taking the unweighted mean of all the individual nest hatch successes. Hatching success is the percentage of eggs in a nest that produce hatchlings. Any hatchlings found during excavations, live or dead, were considered hatched. Mean hatch success for 2015 was 56.8% (Appendix A). 80 nests had >91%, 55 nests had 81-90%, 28 nests had 71-80%, 8 nests had 61-70%, 8 nests had 51-60%, 6 nests had 41-50%, 6 nest had 31-40%, 7 nest had 21-30%, 9 nests had 11-20%, and 12 nests had <10% hatching success (Figure 4).

Storm, Tide, and Overwash Loss

During the 2015 sea turtle nesting season, 20 nests were completely lost (3) or washed away (17) by significant storm and tide events (Figure 4., Appendix A). Lost is defined as a nest that is still in the ground but not recovered. Washed away is defined as a nest that no longer exists in the ground.

Full moon tides with SSW winds > 25 mph (7/1 – 7/4) washed away 2, excessive erosion from SW winds > 20 mph (7/12 – 7/14) washed away 1, a nor’easter front with NE winds > 25 mph (8/9 – 8/11) resulted in a loss of 1, abnormal tidal fluctuation and NE wind > 20 mph (8/25 – 8/31) washed away or lost 2, and a nor’easter front with winds > 25 mph and abnormal tides (9/22 – 9/29) washed away or lost 14. In addition, 63 of the 78 nests with a hatch success rate ≤ 30% (not including lost nests) were significantly impacted by Hurricane Joaquin and these storms (Figure 4). Excessive water inundation, over-washes, sand accretion, and sand loss over the top of these nests were contributing factors to their poor hatch and emergence successes.

Strandings

In 2015, 286 stranded sea turtles were documented within CAHA (Table 2.) Volunteers associated with The Network for Endangered Sea Turtles (N.E.S.T.) assisted Resource Staff by reporting and sometimes responding to observed strandings.

Table 2. Sea turtle strandings at CAHA by species, 2009–2015.

|

Year2 |

Stranding Totals |

Species Composition |

|||||

|

Loggerhead |

Kemp's Ridley |

Green |

Leatherback |

Hawksbill |

Unk. |

||

|

2009 |

297 |

53 |

57 |

183 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

2010 |

444 |

100 |

108 |

235 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

2011 |

148 |

50 |

46 |

49 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

2012 |

126 |

34 |

32 |

50 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

|

2013 |

189 |

38 |

52 |

94 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

|

2014 |

219 |

50 |

61 |

104 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

2015 |

286 |

44 |

39 |

198 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

2 Total stranding numbers for 2008-2011 include some strandings that occurred outside of CAHA boundaries

Of the 286 strandings, 34 (12.8%) were found alive and transferred to the North Carolina Aquarium’s, Sea Turtle Assistance and Rehabilitation Center (STAR) on Roanoke Island or a similar facility for rehabilitation.

Efforts were made to necropsy dead strandings to determine possible cause of death, gender, any abnormalities, and to collect requested samples for ongoing research. Gender was determined in 98 strandings (54 female, 39 male). Samples collected during necropsies, including eyes, flippers, muscle, foreign debris, and tags, were provided to cooperating researchers. Probable cause of death, when possible, was determined by NCWRC (Table 3). During periods of cold water temperatures (7-10° C), sea turtles are most prone to stranding due to hypothermia (Spotilla 2004), which is often referred to as “cold stunning”.

Table 3. Probable cause of sea turtle strandings at CAHA by month, 2015.

|

Month |

No Apparent Injuries |

Cold Stun |

Other |

Boat |

Entanglement |

Pollution / Debris |

Disease |

Shark |

Unable to Assess |

Total |

|

January |

8 |

33 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

41 |

|

February |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

March |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

April |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

May |

5 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

12 |

|

June |

4 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

July |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

August |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

|

September |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

|

October |

15 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

21 |

|

November |

35 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

46 |

|

December |

121 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

130 |

|

Total |

204 |

33 |

8 |

16 |

8 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

12 |

286 |

Discussion

Turtle Sense: Developing a Sensor to Detect Hatching and Emergence at Sea Turtle Nests

Cape Hatteras National Seashore (Seashore) collaborated with Samuel Wantman and David Hermeyer (Nerds Without Borders-NWB) and Eric Kaplan (Hatteras Island Ocean Center-HIOC) for the third year, to develop a sensor that is placed in turtle nests to monitor movement and temperature fluctuations. The hope is to be able to correlate the measurements with hatching and emergence events. The Seashore purchased the sensors and communication towers through HIOC and was responsible for implementing the project in the field.

In 2013, the initial year of the study, four prototype sensors were deployed. The sensors were placed on top of the uppermost eggs at the time of nest discovery and then connected to communication towers closer to expected hatch time. Data collected by the sensors was transmitted every two hours and a computer model analyzed the data. The project got off to a late start and sensors were placed in late season nests. Unfortunately, none of the turtle nests that were being monitored hatched. Through the 2013 – 2014 offseason, communication and design issues were addressed and the second phase of sensors and equipment were constructed by the above collaborators.

In 2014, the second phase of the study, 19 sensors were deployed during the nesting and season. All viable nests that hatched showed significant movement patterns as hatching occurred throughout the season. Only one out of the 19 sensors malfunctioned and did not record any data.

In 2015, the third year of the study, 31 sensors were deployed from May 23 through September 4. One nest with a sensor was frequently overwashed during incubation and observed in standing water the day the communication tower was scheduled to be installed. Although this nest had a sensor it was never monitored because it was never attached to the communication tower. In 2015 the sensors were deployed below the top layer of eggs, a change in protocol from the previous years. Sensors were placed on top of the uppermost eggs in 2013 and 2014.

Of the 30 nests that were monitored, 22 successfully predicted hatching events. Of these nests, 12 emerged when predicted (+/-1 day), 8 emerged more than 1 day after the predicted date, 1 emerged more than 1 day before the predicted date, and 1 nest was infertile. Of the nests with hatchlings that emerged later than predicted, two nests with hatchlings were “saved” because the sensors had indicated that the eggs had hatched (but hatchlings hadn’t emerged) and the nests were checked early because of imminent overwash. Another nest was late because a thick layer of “crust” had formed above the nest preventing the hatchlings from emerging. Of the 8 remaining nests with sensors where predictions were not made, two nests had very few live hatchlings (<10%), two nests had equipment failure, two nests were infertile and excavated before predictions could be made, and two were washed away during a storm.

DNA Study

Since 2010, CAHA, along with all other North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia beaches, has participated in a genetic mark-recapture study of Northern Recovery Unit nesting female loggerheads using DNA derived from eggs. The study is coordinated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the University of Georgia, and NCWRC. One egg from each nest is taken and sampled for maternal DNA. This allows each nest from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia to be “assigned” to a nesting female. This research ultimately will answer questions about the total number of nesting females in the population, the number of nests each female lays per season, distance between nests laid by individual females, and other information that is important to understanding the population dynamics of sea turtles.

Depredation

National Park Service staff documented 28 hatchlings from 6 different nests being depredated by ghost crabs. Fourteen eggs from one nest were depredated by birds. No mammalian depredation of eggs or hatchlings was documented, however tracks from mammalian predators (feral cat, dog, raccoon, mink, etc.) were observed at nest sites on mornings following hatching events. Two hundred eighty eight (288) eggs were taken for DNA analysis; this includes six eggs that were punctured by the observer’s finger when searching for the origin of the eggs and oneegg trampled by a pedestrian before the nest was protected. Six eggs from one nest were opened by observers to check for viability due to excessive over-wash and standing water near the nest hatching window (Appendix A).

Ghost crabs depredated 76 eggs from 12 nests prior to nest excavations. Ghost crab depredation of 28 hatchlings from 6 nests was also documented, but the full extent of hatchling depredation by ghost crabs is unknown. Observations were made of ghost crabs in the act of predating hatchlings. These observations occurred within nest cavities during excavations as well as after hatching events inside of ghost crab holes in the vicinity of the nest site.

Late Nest Management

A late nest refers to a nest that is laid on or after August 1 and incubates for longer than 90 days. In 2015, no nests fit these criteria. Twenty three nests were laid on or after August 1; 6 hatched in < 75 days of incubation, 17 were washed away or lost to storm events. Following NCWRC recommendations, after 90 days of incubation, an excavation would begin on any late laid nests. If a viable embryo was observed, the excavation would be stopped and the nest would be left in place. If hatching activity was not observed after 100 days of incubation, any closure extending to the water would be removed and the nest site itself would remain protected by a smaller closure. The eggs would then be checked approximately every 10 days for viability. Nests would be fully excavated when no viable embryos are observed.

Nesting Activity on Private Property Adjacent to CAHA

Superintendent’s Order #25 was effective beginning in May, 2013. This order established Park protocols which personnel implemented when sea turtle nesting activity was observed on private property. In these instances, property owners were contacted in order to request access to their property for data collection and to carry out possible protection measures. This season, no nests were discovered to have been laid on private property throughout the CAHA.

Incidental Take / Human Disturbance

All species of sea turtles nesting at CAHA are protected under the ESA of 1973. Under the ESA, “take” is any human induced threat to a species that is listed. Take is defined as “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, capture or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” Harm is further defined to include significant habitat modification or degradation that results in the death or injury to listed species by significantly impairing behavioral patterns such as breeding, feeding, or sheltering.

Park staff documented one instance of human disturbance that resulted in one egg being trampled and broken from a single nest on Ocracoke Island. The single pedestrian came upon a nesting Loggerhead sea turtle and thought that it was in distress, the pedestrian proceeded to dump sea water on the nesting female in order to “revive” it. While walking around the unprotected nesting female, one egg was trampled. Park staff was able to respond to the incident and use the trampled egg for DNA analysis.

There is little known to what extent human activities disrupted sea turtle nesting activities during the 2015 nesting season. People on the beach at night can disturb female turtles during the egg laying process. From the time a female exits the surf until she has begun covering her nest, she is highly vulnerable to disturbance, especially prior to and during the early stages of egg laying. Much of CAHA’s shoreline remains open to pedestrians and CAHA staff is unable to monitor the entire shoreline for nesting turtles 24 hours a day. Staff minimized some of these effects by closing the shorelines to non-essential ORV use from 9:00 p.m. until 7:00 a.m. to provide for sea turtle protection.

Closure Violations

Closure violations are documented whenever possible by resource management staff. A total of 164 pedestrian violations (64 instances) of turtle closures were documented. In addition, 22 cat (21 instances), 36 dog (31 instances), two fox (2 instances), and 10 ORV (6 instances) violations of turtle closures were also documented. No direct loss of eggs or hatchlings was documented due to a closure violation.

Artificial Lighting

This year, misorientation (directed movement of a hatchling towards an inappropriate object or goal) or disorientation (lack of directed movement towards a specific area or goal) was documented at 13 nests, totaling 235 hatchlings or hatchling tracks observed to be affected (Appendix A). In most situations hatchling tracks was the only evidence to show hatchlings were being disrupted from their normal movement to the ocean and little is known on the fate of these hatchlings because they were never recovered.

Since the majority of nests are not observed during hatching events, the extent of hatchling loss due to artificial lighting is unknown. Artificial light is known to disturb nesting females and disorient hatchlings. Outdoor lights, beach fires, and headlights may deter nesting females from laying their nests along stretches of optimal beach. Hatchlings use natural light to navigate toward the water. When artificial lights are brighter than the natural light reflecting off the surface of the ocean, hatchlings will become disoriented and crawl away from the shoreline and toward these brighter lights and the dunes. This causes hatchling mortality due to exhaustion and increased chance of predation.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore continues to try and decrease the effects of artificial lighting on sea turtles. Since 2005, black silt fencing has been utilized around most turtle nests to decrease the amount of artificial light shone onto the beach, thereby decreasing the negative effects of light on hatchlings. In 2012, a Superintendent’s Order was established that sets outdoor lighting guidelines within CAHA’s boundaries. In the 2013-2014 seasons, CAHA staff worked with cooperating agencies on an educational public outreach campaign focusing on the effects of artificial lighting on sea turtles. Brochures and light switch stickers were printed and dispersed to the public as well as placed in many rental homes on Hatteras Island. This season, CAHA staff continued their efforts to educate the public on artificial lighting by dispersing brochures to the public at sea turtle nests due to hatch. Efforts were also made to encourage vacationers at their rental homes to shut off all artificial lighting not being used during nighttime hours.

The ORV Management Plan regulates off-road night driving, which has the potential to decrease disturbance from headlights on nesting female turtles and hatchlings. Night driving was prohibited from May 1 through September 15 from 9:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. Starting September 16, night driving was systematically re-opened as nests were excavated and closures removed.

Recreational Beach Items

Recreational beach items (i.e. shade canopies, furniture, volleyball nets, etc.) that remain on the beach at night can cause turtles to abort their nesting attempt (NMFS, USFWS 1991). These items can cause a visual disturbance for nesting turtles and/or can act as a physical impediment. During the 2015 nesting season resource management staff continued to tie notices to personal property found on the beach after dawn, advising owners of the threats to nesting sea turtles as well as safety issues and National Park Service (NPS) regulations regarding abandoned property. Efforts were made by all, beach roving NPS staff, to contact and educate visitors of the issues concerning property left on the beaches overnight. Items left on the beach 24 hours after tagging were subject to removal by NPS staff.

References

Bustard, Robert H. and Greenham, P. 1968. Physical and chemical factors affecting hatching in green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas (L.). Ecology, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 269-276.

Epperly, Sheryan P., Braun, J., and Veishlow, A. 1995. Sea turtles in North Carolina waters. Conservation Biology, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 384-394.

National Marine Fisheries Service and Fish and Wildlife Services. 2008 Recovery Plan for the Northwest Atlantic Population of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle. Washington, DC: National Marine Fisheries Service.

National Park Service. 2010. Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement. U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, North Carolina.

North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission. 2006. Handbook for Sea turtle Volunteers in North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Spotilla, James R. 2004. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Biological Opinion the Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan for Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Dare and Hyde Counties, North Carolina. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Raleigh Field Office, Raleigh, NC. 156 pp.

Appendix A. 2014 Project Summary Report/Guide for CAHA Sea Turtle Nests

Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System Project Summary Report

|

Survey N Boundary |

Ramp 1, Bodie Island (excludes Pea Island NWR) |

|||

|

Survey S Boundary |

South Point, Ocracoke |

|||

|

Length of Daily Survey (km) |

104 km |

Total Kilometers Surveyed |

16016 |

|

|

km = miles x 1.6 |

||||

|

Total Days Surveyed |

150 |

Days per Week Surveyed |

7 |

|

|

Time of Day Surveyed |

Morning |

Number of Participants |

11 |

|

|

Date Surveys Began |

4/30/2015 |

Date Surveys Ended |

9/30/2015 |

|

|

Date of First Crawl |

5/6/2015 |

Date of Last Crawl |

9/04/2015 |

|

|

Date of First Nest |

5/13/2015 |

Date of Last Nest |

9/04/2015 |

|

|

Total Nests |

289 |

Undetected |

1 |

|

|

Nesting Density (nests/km) |

2.77 |

Disoriented/Misoriented |

13 (nests) |

|

|

In Situ |

233 |

Washed Away Tide/Storm |

17 |

|

|

Relocated |

56 (19.3%) |

Depredated |

19 |

|

|

False Crawls |

242 |

Unknown |

0 |

|

|

Mean Clutch Count |

116.5 |

Incubation Duration (All) |

56.9 |

|

|

Hatchlings Produced |

18644 |

Incubation Duration (In situ) |

57.3 |

|

|

Hatchlings Emerged |

15960 |

Incubation Duration (Relocated) |

55.6 |

|

|

|

||||

|

MEAN |

MEAN |

NEST |

BEACH |

|

|

56.80% |

48.80% |

65.0% |

54.4% |

|

|

IN SITU: 55.4% |

IN SITU: 47.4% |

IN SITU: 63.0% |

TOTAL NESTS: 289 |

|

|

RELOCATED: 62.7% |

RELOCATED: 55.1% |

RELOCATED: 73.2% |

TOTAL CRAWLS: 531 |

|

|

Eggs Lost |

||||

|

Research |

281 |

Ghost Crab |

76 |

|

|

Birds |

6 |

Tide / Storm |

14 |

|

|

Other |

6 |

Broken eggs |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hatchling Loss |

||||

|

Misorientation |

13 (nests), 235 (tracks or hatchlings) |

Ghost Crab |

28 |

|

|

|

|

Other (Opossum) |

1 |

|

For Appendix B, select the Sea Turtle 2015 Annual Report from Cape Hatteras Appendix B: Maps article.

Last updated: December 11, 2017