A total of 15 colonies containing 2 or more nests within 200m were documented in 2015. Hatteras Island contained 12 colonies; Bodie Island, Ocracoke Island and Green Island contained 1 colony. Of these observed colonies, 6 met the requirements for consideration of future pre-nesting closure placement. The total number of nests for least terns, common terns, Forster’s terns and black skimmers decreased during the 2015 breeding season; the gull-billed tern nest count slightly increased.

Introduction

Colonial waterbird refer to those species of birds that nest in large groups or colonies and obtain their food from the water. Terns, gulls, pelicans, skimmers, and cormorants are all examples of CWB. The beaches of CAHA provide traditional nesting habitat for several species of special concern and state-listed colonial-nesting waterbirds, including the common tern (Sterna hirundo), least tern (Sterna antillarum), and black skimmer (Rynchops niger). Less common nesters include the gull-billed tern (Gelochelidon nilotica) and Forster’s tern (Sterna forsteri).

Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation

On February 15, 2012 the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation (ORV Management Plan) was enacted. It was developed from 2007-2012 and was accompanied by a special regulation detailing requirements for off-road vehicle (ORV) use at CAHA. A copy of the ORV Management Plan and other related documents are available electronically at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/caha. The ORV Management Plan includes establishment of pre-nesting closures and buffer requirements for nesting birds and chicks as well as the requirement for an ORV permit to drive on CAHA beaches. It states that “Concentrations of more than 10 CWB nests in more than one of the past five years and new habitat that is particularly suitable for shorebird nesting…will be posted as pre-nesting closures…by Apr 15.” This is the fourth year the ORV Management Plan has guided the management of protected species at CAHA.

Methods

Resource Protection Closures

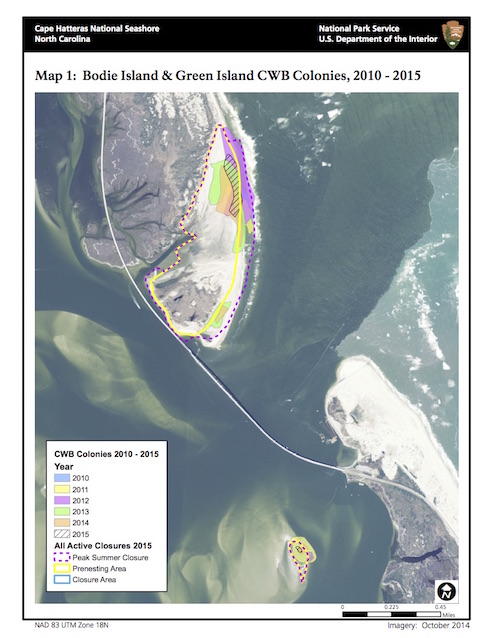

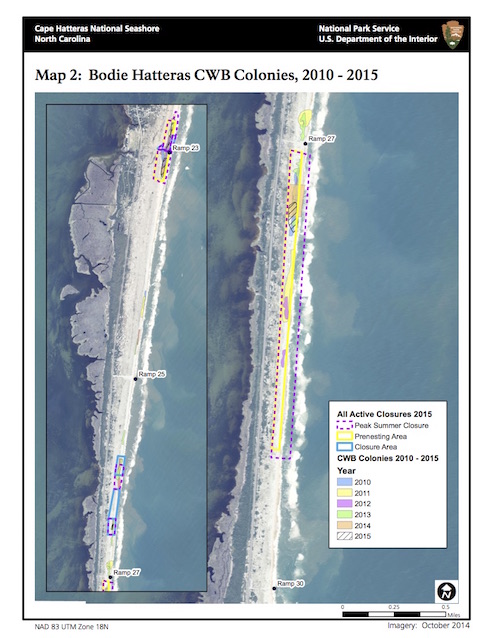

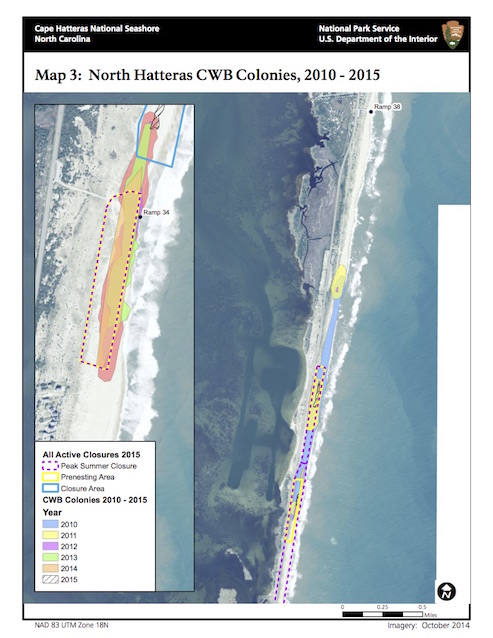

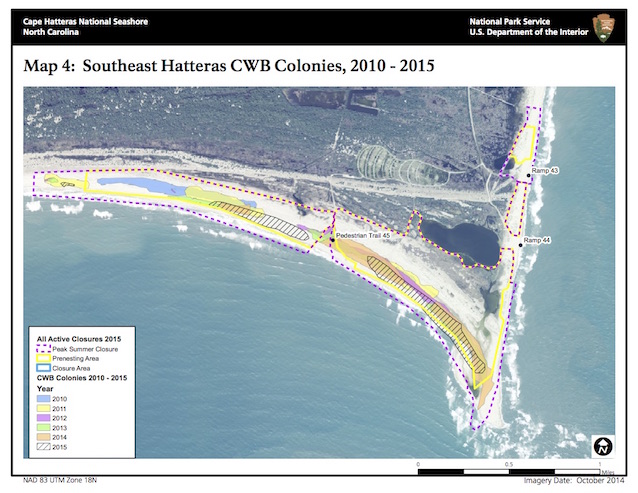

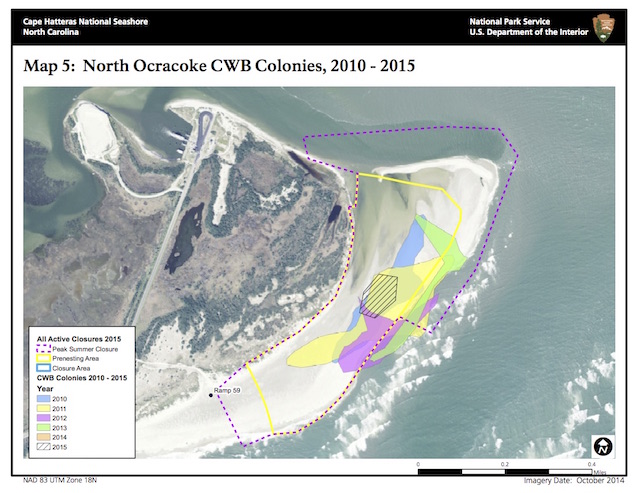

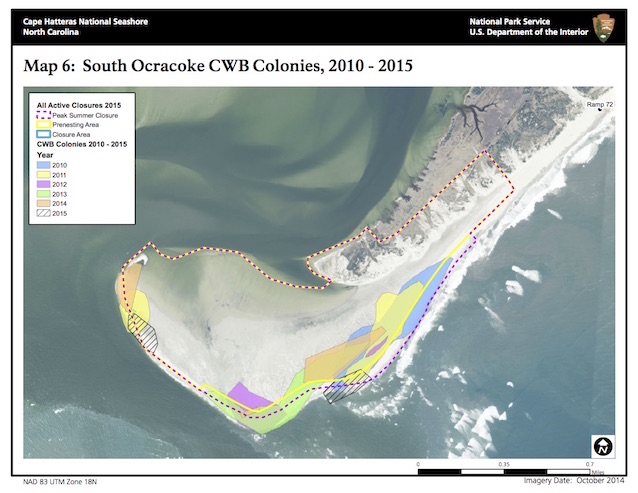

In addition to the pre-nesting closures established for piping plovers (PIPL) and American oystercatchers (AMOY), pre-nesting closures for CWB were installed by April 15, 2015 in areas where the habitat was suitable for nesting and where nesting had occurred in more than one of the past five years (Appendix A, Maps 1-6). This included areas where pre-nesting closures had not been established for PIPL and/or AMOY earlier in the breeding season. As per the Final ORV Management Plan, LETE buffers were 100 meters for breeding behavior (scrapes or nests) and 200 meters for unfledged chicks. Other protected CWB species received a 200 meter buffer for all breeding and nesting activity (Table 1). Closures were modified as the colonies expanded or nests hatched to maintain the required buffer sizes from the outer-most nest or chicks in the colony. When multiple species were present, the greatest applicable buffer distance was applied.

Table 1. Colonial waterbird (CWB) nesting and chick buffers at CAHA.

|

|

Breeding Behavior and Nest Buffer (m) |

Unfledged Chick Buffer (m) |

|

LETE |

100 |

200 |

|

Other protected CWB |

200 |

200 |

Monitoring

Monitoring of CWB at CAHA focuses on identifying nesting habitat, protecting nesting areas and chicks, and monitoring colony activity. In addition to established pre-nesting closures, technicians were responsible for locating additional areas where active colonies may begin to form. This involved observing CWB for courtship, copulation, and scraping behaviors. Initialization of data collection began when scraping behavior or physical scrapes were observed and a closure (with applicable buffers) was installed around the area. Once a closure was established, the area was observed at least once daily from either outside the closure or inside the closure at the shoreline by resource management field staff. Efforts were made to minimize entry into colonies to minimize colony disturbance.

A minimum of two walk-through nest-abundance surveys were performed for each colony to more accurately count and determine the size of the colony. The highest count was reported as the nesting peak. The estimated peak nesting for CAHA is generally within the first part of June, but this may be advanced or delayed based on the start date and progression of the colony. If chicks have been observed prior to the first week of June then it is acceptable to perform a walk-through survey. The distance from the outer most nests or chicks to the closure boundary were checked during observation periods to ensure all nests or chicks were within the required buffer.

Predator Control

Depredation by mammals has the potential to affect the success of a colony, thus predator control continues to be a tool in aiding with the success of established colonies. During the 2015 breeding season, the trapping program at CAHA was not implemented due to insufficient staffing needs. The colonies were allowed to progress with naturally occurring predators in their presence. When field staff walked through and surveyed areas, they documented any natural signs (e.g. track or scat) of predators for future reference and to determine if predator pressure may have affected the status of the colony.

Results

Observed Colonies

The ORV Management Plan does not specify what parameters constitute an active CWB colony. Based on the current protocol Colonial Waterbird (CWB) Management at Cape Hatteras National Seashore, “Each distinct group of nesting CWB will be considered a colony and receive a name designation if there are 2 or more nests within 200m or less of one other.” Also, activity that triggers a resource protection closure must include physical evidence of established breeding such as a scrape or a nest; behavior alone (e.g. copulation or fish-flashing) will not suffice. A total of 15 colonies (Table 2) with 2 or more nests within 200m were observed within CAHA during the 2015 breeding season. If not already present, a closure with proper buffering was installed to provide the colony with protection. Under the ORV Management Plan, locations of colonies containing more than 10 CWB nests will be considered for future placement of pre-nesting closures.

Table 2. Summary of colonies observed during the 2015 breeding season.

|

|

Observed Colonies |

Colonies with More than 10 Nests |

|

Bodie Island |

1 |

0 |

|

Green Island |

1 |

0 |

|

Hatteras Island |

12 |

5 |

|

Ocracoke Island |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

15 |

6 |

Nest Observations and Counts

Similar to previous years, individual colony walk-throughs occurred during the peak nesting period for each colony. The walk-throughs were conducted a minimum of two times during peak nesting and potentially a third time if circumstances necessitate. A third survey was likely if either a colony start date is early or delayed, if there is predator influence, if storms/weather significantly impact colony sites, or if the colony has grown and more accurate information regarding breeding estimates can be obtained.

Table 3. Total nests, eggs, and chicks documented per species during peak nesting surveys; 2015.

|

|

Nests |

Eggs |

Chicks |

|

LETE |

291 |

581 |

26 |

|

COTE |

16 |

33 |

6 |

|

GBTE |

3 |

5 |

0 |

|

FOTE |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

BLSK |

85 |

168 |

15 |

Peak nest counts (Table 3) produced a park total of 291 LETE nests with 26 observed chicks, 16 COTE nests with 6 observed chicks, 3 GBTE nests, 2 FOTE nests, and 85 BLSK nests with 15 observed chicks. On Ocracoke, 15CWBOI01 was the only species-diverse and most productive colony on the seashore, containing LETE, COTE, GBTE, and BLSK. The colony on Green Island, 15CWBGI01, was reached by way of kayak but only under safe, weather-permitting conditions; active nesting behavior was observed only once during the 10-day duration of this colony. For a third consecutive season, multiple FOTE nests were documented on Green Island, while COTE were observed showing territorial but not nesting behavior.

Three CWB breeding locations were established and lost before colony status could officially be established prior to the walk-through survey dates.

- 15CWBHI02 on Hatteras Island was active (LETE scrapes only) from May 15 – May 22. The gradual reduction in LETE activity within one week was thought to be caused by a either a weather event or the presence of predatory pressure.

- 15CWBOI02 on Ocracoke Island was active (LETE scrapes only) from May 21 – July 3. A consistent group of at least 10 adults was observed for the entire duration but no physical nests were documented. Four LETE chicks were observed during the 2nd walk-through survey but they may have ventured from the nearby 15CWBOI01 colony 0.5 mile away.

- 15CWBOI03 on Ocracoke Island was active (LETE scrapes only) from May 22 – June 4. Predator pressure likely caused the abrupt end of breeding activity. Mink tracks were documented within the area on May 26.

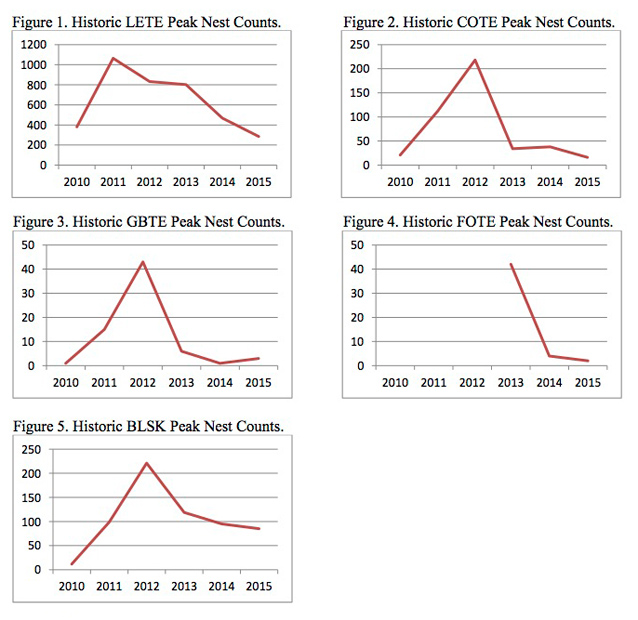

Historical Comparison

With the exception of a minimally higher GBTE nest count, the total number of documented nests for the remaining species in CAHA were lower in 2015 (Figures 1-5). The FOTE nests, though lacking data from 2010-2012 breeding season, were also lower. South Point on Ocracoke was the only location that produced COTE, GBTE, and BLSK numbers. The high abundance of Laughing gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla) nesting on Green Island was likely responsible for the absence of nesting COTE and BLSK; FOTE nest numbers were also minimal and for a 2nd consecutive year. Tern species on Green Island have resorted to nesting on elevated clumps of grass in the interior of the island that is prone to flooding; the gulls inhabit the preferred outer portions of habitat. The BLSK nest numbers fell below the park average and 2015 saw a great decline in documented chicks (15 chicks) for this species. The GBTE still remain low in terms of nesting numbers and they were only observed on Ocracoke for a third consecutive year.

Productivity

Productivity in unmarked CWB colonies is very difficult to determine. While it is certain many colonies fledged chicks, there are no definitive numbers for CWB productivity at CAHA. The uncertainty remains as to whether or not the fledglings observed are from that particular colony or just passing through from elsewhere. Of the 15 documented colonies, LETE fledglings were observed in 9 colonies while BLSK and COTE fledglings were only observed on South Point (15CWBOI01).

Nest and Chick Loss

hree factors at CAHA are thought to contribute to the loss of nests or chicks on a yearly basis: predator disturbance, abandonment, and weather. On multiple occasions, more than one factor may occur. The heavy abundance of ghost crabs throughout the seashore is a continuous threat that all nesting CWB face. Predator interactions were documented in 10 of the 15 observed colonies; documented predators include coyote (28 interactions), opossum (5 interactions), feral cat (3 interactions), gulls (2 interactions), fox (1 interaction), and mink (1 interaction). Perpetual predators that affect localized colonies include coyote disturbance on Bodie Island spit and mink on Ocracoke Island. Constant pressure from predators has proven to lead to colony abandonment in the past. During the 2015 CWB breeding season, there were no significant weather events that were thought to negatively affect nesting or chicks at Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Human Disturbance

Human disturbance, direct or indirect, can lead to the abandonment of nests or loss of chicks. Throughout the 2015 nesting season, field staff documented 18 cases of pedestrian violations involving 87 people, and 1 Off-road Vehicle (ORV) intrusion within a resource protection closure containing CWB. Additionally, 3 cases of dog violations (4 individuals) were documented as well as 2 cases involving pedestrians on bicycles traversing a resource protection closure containing CWB. Most unlawful entries were not witnessed, but documented based on pedestrian, vehicle, or dog tracks left in the sand. The numbers are conservative since sites are not monitored continuously, weather erases tracks, and field staff did not disturb an incubating pair or young in order to document disturbance. The number of documented cases indicates violations to closures specifically containing nesting CWB or habitat protected for CWB. It is important to note that most of the closures contained multiple species including CWB, AMOY, and/or PIPL. Visitors’ unleashed dogs are continuously a threat to protected species attempting to nest on the beach.

Discussion

The 2015 CWB nesting season resulted in fewer nests in four of the five species that were documented to nest at CAHA. Typically, pressure from predators will always be a factor that affects nesting shorebird colonies at CAHA. Given that the trapping program at CAHA was not utilized during the breeding season, this likely resulted in continuous predator pressure that in-turn led to lower success of colonies. In 2015, only 3 CWB areas did not endure long enough to attain true colony status of 2 or more nests within 200m (vs 8 CWB areas in 2014). This was likely due to the absence of significant storm events during the breeding season, which allowed most CWB to commit to nesting in their desired areas.

Even though three more colonies were documented than the previous year, overall nest numbers were still lower. This may be the result of larger colonies breaking apart into smaller ones as influenced by presence of pedestrians near villages or pressure from predators. The installation of yearly pre-nest closures and maintenance of appropriate buffers may have had a positive influence on the number of CWB pairs nesting at CAHA by providing less human pressure within nesting habitat.

Two walk-through nest-abundance surveys were performed during peak breeding for a third consecutive year. These surveys were performed for each colony to aid in refining nest counts and to more accurately classify colonies; the survey having the highest count was reported as the nesting peak. Resource Management staff has made a greater effort to quantify birds documented in incubating posture as an alternative to conducting more frequent walk-through counts outside of peak nesting. Although we are losing some accuracy by relying solely on observational skills, nesting shorebirds have benefited from less obtrusive methods of monitoring.

Appendix A: Maps

Map 1: Bodie Island & Green Island CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Map 2: Bodie Hatteras CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Map 3: North Hatteras CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Map 4: Southeast Hatteras CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Map 5: North Ocracoke CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Map 6: South Ocracoke CWB Colonies, 2010 - 2015

Last updated: December 11, 2017