In 2015, 25 pairs of American oystercatchers (AMOY) nested at Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CAHA). A total of 43 nests were identified in the park which includes re-nests from pairs with failed nest attempts. Of these nests, 19 hatched and produced a total of 38 chicks. Eleven pairs of AMOY were successful in fledging 13 chicks which represents a 0.52 fledge rate per pair.

National Park Service

Introduction

The AMOY is a ground-nesting shorebird native to North Carolina. As with many shorebirds, oystercatcher numbers have been in sharp decline over the past 20 years. The AMOY is designated as a Species of Special Concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in North Carolina. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to beach development has resulted in nesting attempts in marginal habitat. Nesting attempts in marginal habitat is thought to lead to an increased number of unsuccessful breeding attempts. Off-road-vehicle (ORV) use on the beach can lead to direct mortality of chicks and eggs and pedestrian disturbance can indirectly cause loss of nests or chicks. The main cause of direct mortality of chicks and eggs is believed to be mammalian predators. Studies suggest that there is also an interaction between human presence and predation events by mammals. (McGowan 2004) (McGowan and Simons 2006).

ORV Management Plan

On February 15, 2012 the ORV Management Plan was enacted at CAHA. It was developed from 2007-2012 and was accompanied by a special regulation detailing requirements for ORV use at CAHA. A copy of the ORV Management Plan and other related documents are available electronically at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/caha. It includes establishment of an ORV permit system to drive on CAHA beaches. It also establishes pre-nesting closures and buffer requirements for nesting birds and chicks. This was the fourth year the ORV Management Plan guided the management of protected species at CAHA.

Methods

Cape Hatteras National Seashore employs a number of methods in the monitoring and protection of breeding AMOY. These include protection of back-shore habitat; installing pre-nesting closures for birds exhibiting territorial behavior; monitoring of breeding pairs, nests and chicks; banding of juvenile AMOY; removing predators; and adaptively moving closure boundaries to comply with the required buffers of the ORV Management Plan for nests and chicks. Chick movements were monitored daily to ensure they were adequately protected by the established buffers. Breeding behavior is defined as courtship, mating, scraping or other nest-building activities by birds setting up in new or previously established territories. Breeding behavior, nests and scrapes received 150 meter buffers to reduce possible disturbance to courting or incubating adults. Once the nests hatched, 200 meter buffers were maintained around the chicks. Larger buffers were used if individual birds were observed to be disturbed at these distances.

Closures

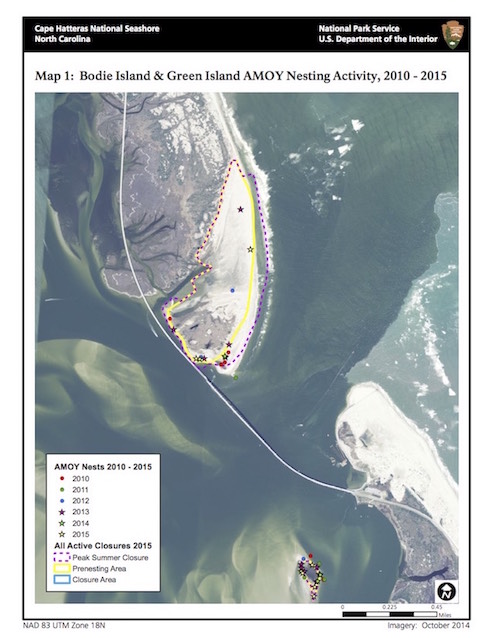

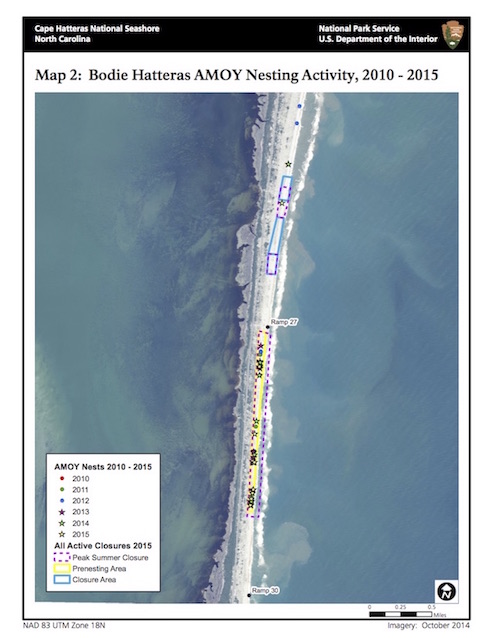

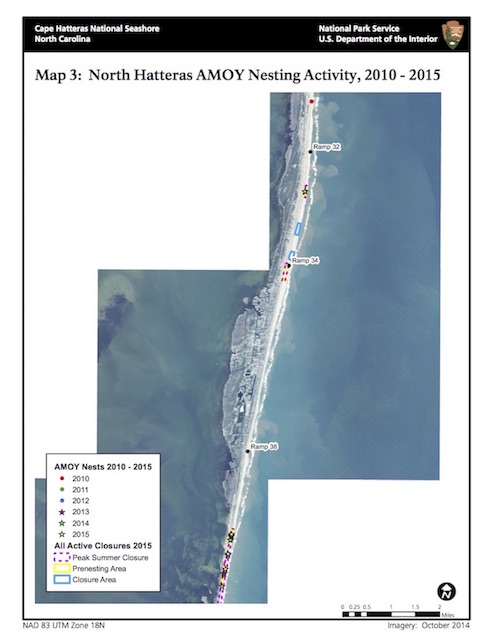

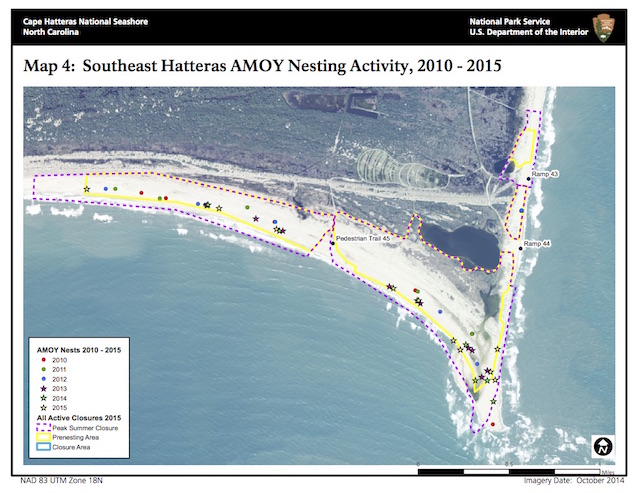

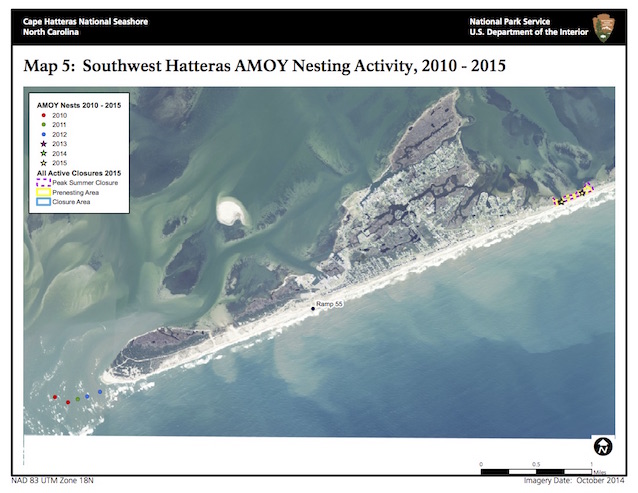

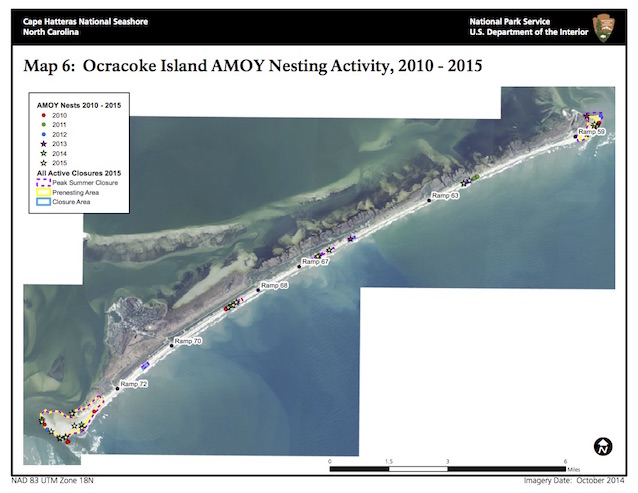

Closures Pre-nesting closures for AMOY were installed in areas where the habitat was suitable for nesting and where nesting has occurred in more than one of the past five years. As per the ORV Management Plan, AMOY required a 150-meter buffer for breeding behavior, scrapes and nests and a 200-meter buffer for unfledged chicks. When multiple species were present, the greatest applicable buffer distance was used. In 2015, 22 AMOY breeding pairs held territories within the pre-nesting closures and 40 of the 43 AMOY nesting attempts occurred inside the pre-nesting closures (Appendix A; Maps 1-6).

Monitoring

Breeding pairs of AMOY were located by surveying potential habitat including ocean-side beaches and sound-side beaches. Birds were monitored closely for nesting when observed regularly at the same location or when demonstrating territorial or breeding displays. If nests or scrapes were found, observers marked the location with a handheld GPS unit. Closures were installed (or modified) as necessary to maintain the required buffer distance(s). Incubating pairs with nests were monitored daily and observed even more closely near expected hatch dates. Expected hatch dates were calculated from an average nest incubation period for AMOY as 29 days from first egg laid or 24 days from last egg laid (Baicich and Harrison 1997). If an incubating bird was not observed on the nest, the nest was checked for the presence of eggs and, if the eggs were missing, the area was inspected for signs of predators. Once chicks hatched, staff attempted to observe each chick daily barring severe weather.

Incubating pairs with nests were monitored daily and observed even more closely near expected hatch dates. Expected hatch dates were calculated from an average nest incubation period for AMOY as 29 days from first egg laid or 24 days from last egg laid (Baicich and Harrison 1997). If an incubating bird was not observed on the nest, the nest was checked for the presence of eggs and, if the eggs were missing, the area was inspected for signs of predators. Once chicks hatched, staff attempted to observe each chick daily barring severe weather.

Chick Movement

After hatching, staff installed a minimum buffer of 200 meters around AMOY chicks. Chicks have been observed to move as much as 100 meters on the first day after hatching and up to 500 meters or more within the first week after hatching. As the chicks commenced their movement away from the nest sites the closures were expanded when necessary to ensure adequate buffers.

Nonbreeding AMOY Surveys

Three surveys were conducted in all park districts from June 1 to June 5 to account for nonbreeding AMOY. Nonbreeding AMOY are lone birds and pairs of birds, both unbanded and banded, unassociated with nests at CAHA. Surveys were conducted on the same dates in all park districts and a GPS point was taken for each AMOY observed. After the conclusion of the breeding season the highest daily number of nonbreeding AMOY for the seashore over the three survey dates was recorded.

Predator Control

Mammalian predation is a major factor in AMOY nest loss and chick mortality (McGowan 2004). Predator control is conducted to target predators near nests and chicks. Trapping was not conducted in all park districts during the 2015 season.

Banding

In addition to carrying out actions required by the ORV Management Plan, resource management staff banded AMOY chicks under North Carolina State University’s (NCSU) banding permit. Banding aids in tracking survival of individuals, determining breeding success of individual pairs, documenting movement of young birds to other areas, and aids in determining breeding site fidelity. Being able to identify individual birds has also allowed NCSU and CAHA staff to coordinate data with scientists from other states to examine genetics, migration patterns, and long-term survival rates of the AMOY population.

Results

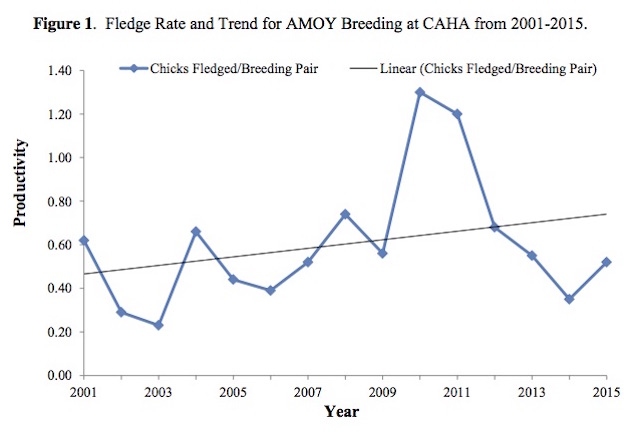

In 2015, 25 pairs of AMOY nested at CAHA. One pair was found on Bodie Island, 13 were found on Hatteras Island, eight were found on Ocracoke Island, and three were found on Green Island. Altogether, these pairs produced a total of 43 nests, including re-nests, of which 19 nests hatched. Eleven pairs were successful in fledging 13 chicks which represents a 0.52 fledge rate per pair (Table 1). Although the chicks fledged per breeding pair at CAHA appears to be cyclical, there is generally an increasing trend in productivity when looked at over multiple years (Figure 1).

| Year | Breeding Pairs |

Total Nests |

Nests Hatched |

Successful Pairs |

Number of Chicks Fledged |

Fledge Rate |

| 2010 | 23 | 28 | 21 | 15 | 30 | 1.3 |

| 2011 | 23 | 26 | 22 | 17 | 28 | 1.2 |

| 2012 | 22 | 30 | 18 | 11 | 15 | 0.68 |

| 2013 | 271 | 42 | 19 | 10 | 15 | 0.55 |

| 2014 | 26 | 38 | 18 | 8 | 9 | 0.35 |

| 2015 | 25 | 43 | 19 | 11 | 13 | 0.52 |

1 Could also be calculated as 26 pairs. One male AMOY nested twice, each time with a different female.

The first nest of the season was found on April 13, 2015 and the last nest was found on June 24, 2015. For the 18 nests with known start dates, the average incubation period was 30.7 days. For the eleven broods which fledged chicks, the average age of chicks when they fledged was 42 days old. This average does not include separate dates for individuals within a brood but is based on the date of the first chick to fledge from each brood.

Nest Failures and Chick Mortality

Twenty-four nests were lost in 2015 breeding season. Three nests were lost to overwash, four nests were abandoned, eight nests were lost to predation, and one nest was lost due to human disturbance. Of the eight nests lost to predation five were taken by coyotes, two by avian predators, and one nest by an opossum. Field cameras documented five incidents of predation; three coyote, one crow, and one opossum. Mammalian, ghost crab and avian predators are believed to be responsible for the other eight nests lost to predation. Repeated pedestrian violations at Cape Point caused one nest to be abandoned. That AMOY pair renested at Cape Point three weeks later and successfully fledged one chick.

Determining cause of chick loss is even more difficult than determining cause of nest loss. In the 2015 season there were eight complete brood failures and seven partial brood failures. Twenty three chicks were lost to unknown causes and one chick was lost during a banding attempt. Chicks can move large distances and it is sometimes difficult to locate them. Environmental conditions surrounding the brood site may obscure evidence of predation and searches for missing chicks may be intentionally delayed since many different types of disturbances may cause the chicks to hide out of view from the observers.

Nonbreeding AMOY Surveys

Three surveys were conducted in all park districts on June 1, 3, and 5, 2015 to account for nonbreeding AMOY. A GPS point was taken for each AMOY observed and breeding pairs were identified after the breeding season concluded. Twelve nonbreeding AMOY were observed on June 3, and 5, 2015. On June 3, six were observed on Bodie Island, two on Hatteras Island, and four on Ocracoke Island. On June 5, five were observed on Bodie Island and seven on Hatteras Island. The age of many of the banded birds is known and some were of age to nest in 2015, but did not, either due to their inability to find, establish and hold a territory, or inability to find a mate of breeding age. Other observed birds will first come into breeding age in 2016.

Human Disturbance

Human disturbance, direct or indirect, can lead to the abandonment of nests or loss of chicks. Throughout the season, resource management staff documented 210 pedestrian, 13 ORV, and 29 dog, boat or horse intrusions in resource closures. The numbers are conservative since sites are not monitored continuously, weather erases tracks, and staff does not disturb incubating pairs or young in order to document disturbance. These numbers indicate violations to closures specifically containing nesting AMOY or habitat protected for AMOY. It is important to note that most of the closures contained multiple species, including AMOY, colonial waterbirds, and piping plovers. Most illegal entries were not witnessed, but documented based on vehicle, pedestrian, or dog tracks left in the sand. Pedestrian entry most often required visitors to lift or stoop under the string that connected all posted signs, while vehicular entry required visitors to drive through or around a sign boundary. Repeated pedestrian violations at Cape Point resulted in one AMOY nest being abandoned. Visitors’ unleashed dogs are also a threat to protected species and continue to be a problem.

Banded AMOY

In 2015, CAHA RM staff banded eight chicks with uniquely identifiable bands. A total of 217 AMOY have been banded at CAHA since 2002 consisting of 48 adults and 169 chicks. As the result of this long term cooperative banding project with NCSU, CAHA has begun to document banded chicks surviving to adulthood and joining the breeding population. Banded birds enabled staff to identify breeding pairs and unpaired individuals with confidence.

Discussion

In 2015, three new AMOY pairs and five new individuals joined the CAHA breeding population for a total of 25 AMOY pairs. Eleven pairs successfully fledged 13 chicks which represents a 0.52 fledge rate per pair. Although the fledge rate is higher than last year increased mammalian predations attributed to low hatch rates. The high number of predation incidents could also be responsible for the increased number of nests. Of the 25 pairs with known nesting dates, 15 pairs re-nested at least once after their nest was lost.

Field staff are trained to identify breeding behaviors associated with territory establishment to allow for the immediate protection of these areas. Adequate protection from disturbance and a continuation of the predator control program should result in a continued increase in population and successful AMOY pairs at CAHA over time.

References

Baicich, P.J. and C.J.O. Harrison. A Guide to the Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (Second edition). Natural World Academic Press, New York. 1997.

McGowan, C.P., 2004. Factors affecting nesting success of American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus) in North Carolina. Unpublished M. Sc. Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina.

McGowan, C.P., T.R. Simons, 2006. Effects of human recreation on the incubation behavior of American Oystercatchers. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 118:485-493.

United States. Dept of Interior. National Park Service. 2010. Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation.” 36 CFR 7. 2012. Print.

Appendix A: Maps

Map 1: Bodie Island and Green Island AMOY Nesting Activity 2010-2015

Map 2: Bodie/Hatteras AMOY Nesting Activity 2010–2015

Map 3: North Hatteras AMOY Nesting Activity 2010–2015

Map 4: Southeast Hatteras AMOY Nesting Activity 2010–2015

Map 5: Southwest Hatteras AMOY Nesting Activity 2010–2015

Map 6: Ocracoke Island AMOY Nesting Activity 2010–2015

Last updated: December 11, 2017