Last updated: February 8, 2024

Article

Butterfly Survey at Lava Cliffs

NPS/V Nalamalapu

On a late summer’s day, I found myself 15 miles up Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. There rests Lava Cliffs, a geologic formation that is the result of volcanic activity 28 million years ago. This is not an area where you would expect to find butterflies: the temperatures are low, the winds are high, and the plants are small and ground-hugging. And yet, butterflies are there. They thermoregulate by angling themselves with the sun, shivering to generate body heat, and taking advantage of the warm crevices between rocks. And, though the plants are small, they are plentiful. Thus, along with many areas around the park, Lava Cliffs is home to a surprising number of butterflies.

NPS/S Mason

The Project

Lava Cliffs is one of six sites that Audubon Naturalist Society Senior Naturalist Stephanie Mason has been monitoring since 1998. These sites, along with 14 others, were chosen in 1997 by Rich Bray, then Rocky Mountain Butterfly Project Lead Investigator, and Dr. Paul Opler, Professor of Entomology at Colorado State University. Bray and Dr. Opler chose these sites as they were accessible, on both the east and west sides of the Continental Divide, at both high and low elevations, and in both wet and dry environments.

NPS/V Nalamalapu

The Purpose

Bray initiated the project in order to understand what species of butterflies are in the park and in what abundances. Furthermore, as butterflies are dependent on plants (most butterflies nectar on flowers and their caterpillars eat leaves and other plant parts), understanding the diversity and abundance of butterflies can be linked to the diversity and abundance of the plants that they are dependent on. Thus, this project has implications for understanding both butterfly and plant diversity and abundance, as well as threats to their protection and conservation.

The Methods

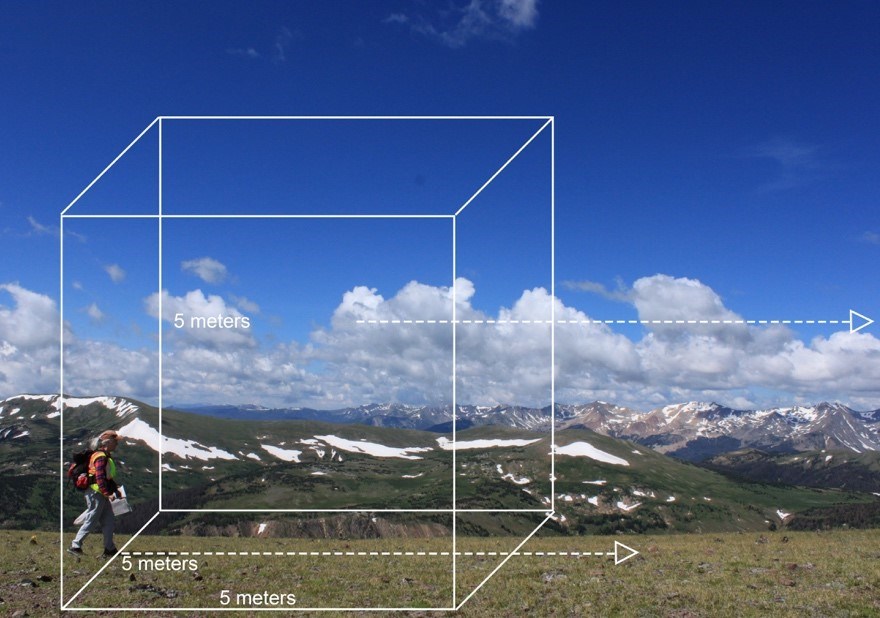

To do this, Stephanie follows a modified Pollard Count Protocol. This protocol consists of her walking along a 1 km transect in each site. While walking, she records any butterflies that fly into her imaginary cube that extends 2.5 meters to her left and right, 5 meters in front of her, and 5 meters above the earth. Additionally, she records the flowering plant species present within 20 feet of the transect. She repeats this multiple times each season, ideally once per week, as weather permits.

NPS/V Nalamalapu

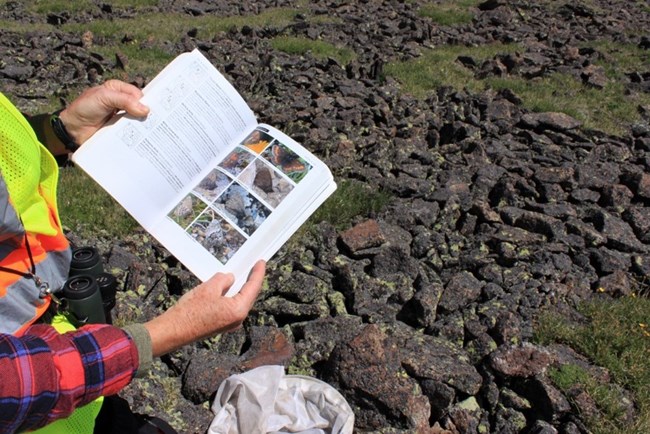

As I walked with Stephanie, I found that her cube easily shattered. Trained as a general naturalist, her curiosity is not easily contained. She was quick to observe and share her observations on everything from the camouflage of white-tailed ptarmigan to feces identification to urine-caused lichen coloration. And then, just as quickly as it shattered, her cube would be pieced back together. She would continue along her transect, leaving me stumbling to catch up, my head brimming with her contagious curiosity and knowledge.

NPS/V Nalamalapu

The Results

The Rocky Mountain Butterfly Project citizen scientists have documented a total of 141 species of butterflies in the park. Over the 21 years that they have been monitoring butterflies, there have been some declines in species’ abundances, yet no species have disappeared completely. This follows the trends worldwide and is at least in part the result of climate change, habitat degradation, and habitat fragmentation. For an insect species to go extinct, there must be either a catastrophic or persistent threat. For now, the threats have been neither catastrophic nor persistent enough to cause extinction. However, if these threats continue, that may change.

Rocky’s diverse environments, as well as its low habitat fragmentation due to its protected status, result in it being home to everything from the Rocky Mountain Parnassian to the Melissa Arctic to the Shasta Blue. As we are deciding the fate of these species, I encourage you to go into Rocky and appreciate the plethora of butterflies that fly in the park today.

Written by Vishva Nalamalapu, Science Communication Intern

Continental Divide Research Learning Center

August 2019