Part of a series of articles titled African American Communities Along the C&O Canal.

Article

Brickyard, Cropley (Carderock), Maryland

Near Carderock, Maryland, just north of the C&O Canal is a little-known historical African American community called Brickyard. Despite the name, the African American community began to settle here before the brickyard was opened. Once the brickyard had established operations, the area became known as Cropley (named for the owners of the brickyard) while many African Americans still lived there. It wasn’t until builders of a segregated subdivision began development in 1928 that the area was renamed Carderock, the name it retains today.

![Cropley PO_The Vicinity of Washington, D.C., 1894 [Map] 1894 map showing Cropley Post Office, Jackson Island, Conduit Road, and a section of the Potomac River.](/articles/images/Cropley-PO_The-Vicinity-of-Washington-D-C-1894-Map_Resized.jpg?maxwidth=1300&autorotate=false)

Repository: Geography and Map Division, Washington, DC. Library of Congress

Cropley Post Office was on Conduit Road, west of the Seven Locks area. As a postal address, Cropley emerged in the 1880s and was named after two large landowners. Richard Lambert Cropley and Arthur Bird Cropley were flour merchants and grocers based in Georgetown who owned over 500 acres in the area now known as Carderock. By the mid-1880s, the Cropley brothers expanded into the ceramics business. In 1894, Arthur Cropley transferred 56 acres south of Conduit Road in Cropley to the Potomac Brick & Tile Company, a business he co-owned with his older brother. This business likely supplied the names of both the road to the west – Brickyard Road – and the historical African American community.

African Americans in Brickyard

African American settlement of Brickyard had taken root a full decade earlier than the establishment of the Potomac Brick & Tile Company. On June 12, 1884, landowner Robert W. Stone sold a half-acre parcel in Cropley to three African American men: Lawton Garner, William Gibbs, and Joseph Toney. These men were trustees of a new school for African American children and intended to erect a schoolhouse on the lot. Given that the African American settlement predates the Cropley brickworks, it is likely that the name “Brickyard” is a canard – the enclave did not emerge as a home for laborers at the Potomac Brick & Tile Company. The 1900 US census of the Potomac District of Montgomery County confirms this. The census shows that William Gibbs and Joseph Toney, two of the three school trustees, were neighbors to 14 other African American households interspersed among several white households. The census also shows that eight of the African American men living in Cropley that year worked on the Washington Aqueduct and seven worked on the railroad; none worked in the Cropley brickworks. Several pieces of evidence imply that the community grew because of the Washington Aqueduct:

- In 1884, the US Army Corps of Engineers solicited and settled some 500 workers in the Great Falls and Carderock areas to extend the Washington Aqueduct dam across the Potomac River;

- The 1900 census says that eight local African American men (a high percentage from 16 families) worked on the aqueduct;

-

And the school for African American children was established in 1884, which could be given as the founding date of Brickyard as well as the start of the Washington Aqueduct dam extension project.

According to a real estate atlas published in 1917, Cropley included two churches and a school on Conduit Road at its intersection with an unnamed private road. This road may be present-day Mountain Gate Drive. The only African American landowners depicted on the map were Joseph Toney (who owned 2.5 acres) and C. Frye (five acres). Both parcels were north of Conduit Road and east of the private road.

Library of Congress / Andrew J. Russell.

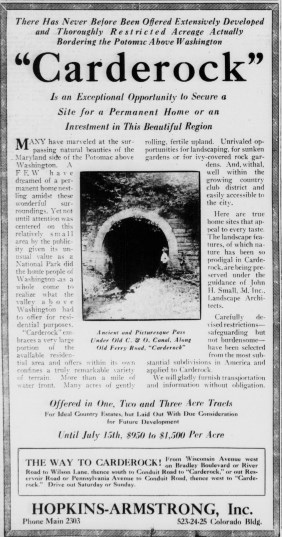

Evening Star, July 1928; Repository: Chronicling America, Library of Congress

Carderock Subdivision

The Potomac Brick & Tile Company operated through 1928. That year, all the Cropley lands between the river and Conduit Road (including the brickyard) were purchased by the Woodside Homes Corporation and platted as a subdivision called “Carderock.” The Woodside Homes Corporation advertised lots in the subdivision in The Washington Post and The Evening Star through the late 1920s and early 1930s as ‘estates’ ranging from two to five acres. The advertisements also said that the subdivision had “carefully revised restrictions,” which alluded to ten covenants written into each deed of title that the company sold to individuals. Among those ten covenants was a racial restriction that prohibited any person of color from owning or renting property in the Carderock subdivision. African Americans in the nearby community of Brickyard were barred from settling in the new subdivision.The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 dashed the Woodside Homes Corporation’s plans. The company made only 11 sales before 1935, when they sold the land to the federal government. The area south of the C&O Canal became part of the C&O Canal National Historical Park, which opened in 1940. From 1938 to 1942 this land was the site of two Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps. These were segregated camps of African American CCC enrollees who assisted the National Park Service in converting the first 24 miles of the canal into public parkland. The area between the canal and Conduit Road was redeveloped as the David Taylor Model Basin in 1938 and 1939 by the US Navy.

What Remains

In the 1930 US census, only a few African American households were listed on Conduit Road in Cropley. However, the Mount Glory Baptist Church (one of the two churches on Conduit Road) had an active Black congregation through the 1940s. The schoolhouse was demolished at some point before 1949, and Cropley’s second church was demolished between 1949 and 1957. In 1963, the Mount Glory Baptist Church property, which lay on the south side of Conduit Road, was bisected by the construction of the Clara Barton Parkway. All the graves in the Mount Glory cemetery were reinterred in a historical Black cemetery in Rockville, the Galilean Fisherman’s (Lincoln Park) Cemetery. Today there are no visible remains of Brickyard’s African American community left on the landscape. It disappeared like so many other places in a nation where neighborhoods have often been thrown up in weeks and taken down just as quickly, where Black communities are replaced by White, and White by Black, rich by poor and poor by rich. From what we see in front of us today we cannot always know everything about what might have been there in the past.Information in this article is included in the Historic Resource Study: African American Communities Along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, by Heather McMahon. Produced by the National Park Service and WSP USA Inc., 2022.

Sources

- “Carderock,” Evening Star (7 July 1928).

- Edward H. Deets and Charles J. Maddox, A Real Estate Atlas of the Part of Montgomery County Adjacent to the District of Columbia. Rockville, MD: 1917. Map. John Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/35333

- “Historic African American Communities in the Washington Metropolitan Area,” Prologue DC [website] (accessed 15 October 2021, https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=5d16635c4fde41eca91c3e2a82c871e8)

- Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the county of Montgomery, Maryland. Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins, 1879. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/87675339/.

- Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. The vicinity of Washington, D.C. Philadelphia: Griffith M. Hopkins, C.E, 1894. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/88693364/.

- Jeff Miller, “Mt. Glory Baptist Church Cemetery [Relocated],” Montgomery County Cemetery Inventory Revisited (Rockville, MD: Montgomery Preservation, 2018, accessed 12 November 2021, https://www.montgomerypreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/226_Mt-Glory_B_Cabin-John_2018_Survey.pdf)

- Montgomery County Deed Book 468, Folio 414, October 2, 1928. [and other land records]

- Robert E. Oshel, “The History of Woodside Park, Silver Spring, Maryland” (Silver Spring: Woodside Park Civic Association, 1998). http://users.starpower.net/oshel/H01.htm.

- US Geological Survey, “Washington Quadrangle,” [MD-DC-VA, 1:62,500] 1909. Map.

- L. Paige Whitley, “The History of the Gibson Grove Community and the Gibson Grove AMEZ Church, Cabin John School and Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 Moses Hall and Cemetery.” Cabin John, MD: prepared for Friends of Moses Hall, January 2021.

Tags

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- national capital region

- national capital area

- ncr

- c&o canal

- choh

- maryland

- montgomery county

- brickyard

- cropley

- carderock

- washington d.c.

- district of columbia

- history

- african american history

- black history

- civil rights

- education

- reconstruction

- reconstruction era

- washington aqueduct

- great falls

- potomac brick & tile company

- urban development

- richard cropley

- william gibbs

- joseph toney

- us army corps of engineers

- civilian conservation corps

- ccc

Last updated: December 11, 2023