From the earliest settlement of the United States, American settlers have conflicted with American Indian neighbors over border and land disputes. Boundary lines established with the American Indians by the British leading into the American Revolution began chafing the American state after independence. This resulted in hostilities and eventually war as the United States dedicated itself to pressing westward at any cost.

The boundaries negotiated by various tribes were meant to stand, at least in Indian eyes, as one Creek chief noted, like “a stone wall never to be broke.”

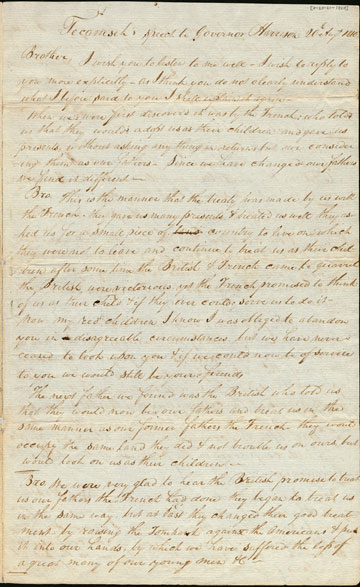

Indiana Historical Society

In the years prior to the American Revolution, the British had attempted to end hostilities and confrontations with Indian tribes along the frontier by implementing a variety of measures to thwart settler encroachment on Indian lands. The Proclamation of 1763, the most notable of these measures, forbade settlement west of a line that sliced through the backcountry of Britain’s Atlantic colonies. The British had sought to mark newly established boundaries between Indians and colonists to end boundary disputes. The boundaries negotiated by various tribes were meant to stand, at least in Indian eyes, as one Creek chief noted, like “a stone wall never to be broke.” By the early 1800s, tribes increasingly came to define themselves as territorial entities with permanent boundaries and the sovereign right to live independently and protect their borders. Although pushed relentlessly by American agents to cede more and more territory, they viewed their territorial boundaries as inviolate: Indian country was for Indian peoples.

American expansion was no myth. Georgia’s population grew to a quarter million, nearly doubling between 1800 and 1810. To the west of Creek country, the Mississippi Territory was established in 1803. Not only did the white and black population grow rapidly there, but the numbers of people crossing Creek lands to reach Mississippi shot up as well. The Creek agent noted 3,700 people had moved along the Federal Road through Creek territory from the fall of 1811 through the early spring of 1812. The new states of Kentucky (1792), Tennessee (1796), and Louisiana (1812) clearly pointed the direction that Americans intended to pursue: settlement and establishment of American hegemony over territories that had once been Indian lands.

It was the same in the Ohio valley. The 1796 Treaty of Greenville, which ended, for a time, the conflicts between Shawnees and Americans, opened former Indian lands to settlement. The new American territory achieved statehood in 1803, and by 1810 Ohio’s population of 230,000 was nearly that of Georgia. Further white expansion into the region had been made possible by the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809) whereby accommodationist Delaware, Miami, and Potawatomi chiefs ceded over three million acres of hunting lands claimed by various Indian tribes to the United States in return for annuities. Other tribes who held claims on the area ultimately ratified the proceedings but only under heavy American pressure. The cession caused divisions among the western tribes, alienated many who had previously counted the Americans as friends, and strengthened opposition to American expansion.

Americans were not only hostile to traditional native cultures and the old trading economy, but also to the foreign powers that threatened to channel Indian discontent over American encroachment into useful alliance. To the north, the British in Canada presented bitter reminders of the way in which the British had used Indian auxiliaries in the American Revolution. Toward the Gulf Coast, Spanish Florida cooperated with trading companies with ties to ex-loyalists who provided an avenue for British trade goods into southern Indian villages.

Part of a series of articles titled American Indians and the War of 1812 .

Last updated: August 15, 2017