Last updated: November 2, 2017

Article

Bison Bellows: Yellowstone National Park

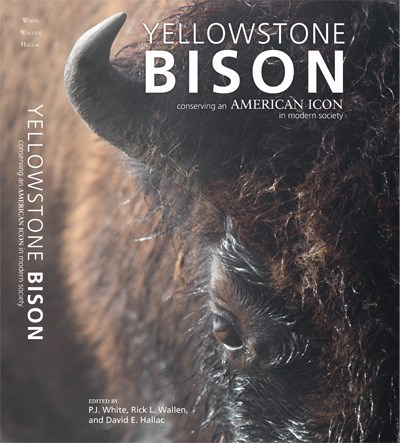

Photo courtesy of authors.

When Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, hundreds or possibly thousands of bison resided in or near the world's first national park. Despite mandates to protect park wildlife, poachers outnumbered protectors and the bison population dwindled until the Lacey Act of 1894 allowed for the prosecution of poachers. By 1902, only 23 bison remained in the Pelican Valley of Yellowstone, the largest remaining wild, free-ranging plains bison herd south of Canada. In the same year, park managers introduced 18 females and 3 bulls from Montana and Texas, respectively, to a few wild bison that were captured and moved from central Yellowstone to the northern region of the park. These bison were initially held in captivity and fed during winters at the Buffalo Ranch in Lamar Valley and by 1928, the northern Yellowstone bison population had grown to about 1,000 bison. In 1936, 71 bison from the northern herd were relocated to bolster the wild bison herd in central Yellowstone. By the early 1950s, there were 1,100 and 1,300 bison in the northern and central herds, respectively. These types of interventions of protection, husbandry, introductions and relocations during the first half of the 1900s were pivotal in restoring the continent's last remnant of wild plains bison.

During the latter half of the 20th century, park management philosophies shifted away from husbandry practices to restoring wild behaviors and allowing bison to move freely within the park. As bison populations roamed more widely, concerns about overgrazing and brucellosis (a bacterial disease that can cause abortions in bison, elk and cattle with potential ecological and economic impacts) incited periodic management removals of bison from the park. During this era, many bison were killed and provided to Native American Indian tribes, relief agencies and contract sales, while live bison were shipped to zoos, reservations and other parks. In 1968, managers stopped culling bison in the park to allow predators, resource limitations and weather to naturally regulate bison populations.

Once bison culling operations were ceased, bison expanded their ranges toward park boundaries. From 1967 to 1984, occasional bison migrants venturing beyond the Yellowstone boundary into Montana were killed to reduce the risk of possible transmission of brucellosis to cattle. Montana managed a state-licensed hunt for bison that left the park from 1985 to 1991 but the number of bison migrating outside of the park continued to increase, prompting the National Park Service to develop management plans to control bison near the park boundaries. From 1985 through 2000, 2,339 bison were captured and shipped to meat processing facilities while 778 bison were shot by hunters or state livestock or wildlife personnel. Intense controversy grew between environmentalists, livestock interests and agency managers, requiring mediation that resulted in the completion of the Interagency Bison Management Plan in 2000. Since then, this plan has been adjusted several times based on new information and changed conditions. Implementation of this plan, however, continues to incite concerns about unintended impacts of management actions to prevent transmission of brucellosis from bison to cattle on the genetics, demography, and restricted distribution of the largest remaining wild bison herd in North America.

Today, Yellowstone bison are distinguished as the largest ecologically and genetically viable wild bison plains bison herd in North America. While the restoration of this important bison population is considered successful, many iterations and adjustments of the Interagency Bison Management Plan highlight the challenges of managing for bison conservation objectives and prevention of brucellosis transmission from bison to cattle. Conserving a wild, free-ranging herd of bison large enough to offset loss of existing genetic variation and to sustain natural ecological processes such as migration and dispersal requires public support and tolerance of bison outside of the park. Reluctance to allow bison to range across larger areas of public lands outside of the park is no longer valid based on the disease issue alone; science and research have demonstrated that the risk of bison transmitting brucellosis is minute compared to elk (which also can transmit the disease) that roam freely and are managed as wildlife. Other concerns will need to be addressed to garner public support of wild bison ranging outside the park such as protection of property, human safety, competition with livestock for grass, allowing bison to range farther from the park to access adequate winter habitat and management of hunting outside of the park. Yet over decades of management, relatively few conflicts have occurred between bison, residents and visitors to the Greater Yellowstone Area, demonstrating that coexistence with wild, free-ranging bison is possible. Acceptance of bison as wildlife outside of parks will enhance bison conservation, enrich visitor experiences, improve public and Native America treaty hunting opportunities, boost local economies, and, hopefully, elicit regional and national pride in this tremendous conservation accomplishment. The time is right to recover bison, our National Mammal and iconic symbol of resilience and strength, as wildlife on appropriate landscapes in the Greater Yellowstone Area.

Did you know?

Brucellosis was transmitted from domestic European cattle to wildlife in Yellowstone before the 1930s, when remote outposts in the park maintained livestock to provide milk and meat to residents and visitors.Available for downloading here.