Last updated: November 2, 2017

Article

Bison Bellows: A Case Study of Bison Selfies in Yellowstone National Park

NPS Photo

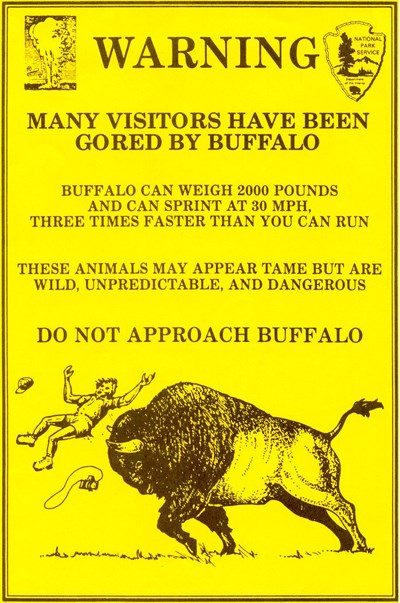

Whether it is taking a "selfie" with a mama moose walking with her calf, a bison grazing alongside a road, or a venomous rattlesnake slithering along a hiking path, it seems that people will do everything they can to get that perfect picture. These selfies have resulted in being seriously bitten, tossed into the air, and gored in the stomach. In 2015 alone, five reported bison-related injuries occurred in Yellowstone National Park. While this number may seem low when over three million visitors travel to the park annually, the question is not if there will be more incidents, but when. Wildlife, especially bison, are dangerous animals and taking selfies only increases the risk of injury and the possibility of death. Not only do these selfies affect people negatively, but they also put wildlife in stressful situations, negatively affecting their health and natural behaviors.

Human-wildlife interactions are increasing globally as more and more people live on the planet. Especially in Yellowstone National Park, one of the five most visited national parks in the United States, human-wildlife interactions occur every minute of every day. These exchanges, especially with bison, can be extremely dangerous. For example, from 2000 to 2015 all reported bison-related injuries in Yellowstone National Park occurred between the months of April and October. This period is during peak mating season for bison, which co-occurs at the same time as peak tourist season. While there were no deaths, people did sustain serious injuries: being tossed, butted, gored, lacerated, bruised, and breaking bones. These injuries happened in the summer range of bison, the area where they are constantly moving around to find food and graze. Bison's summer and winter ranges are concentrated to roughly 40% of the park, which overlaps with the concentration of visitors to 1% of Yellowstone National Park. Both humans and bison are jammed in this space, which only increases the risk for interactions--- it is the highest concentration of bison and people in the entire world!

Social norms absolutely seem to influence these bison selfie and negative human-wildlife incidents. In relation to taking bison selfies, a person might see another person taking a selfie or see a group of people standing close to a bison and think this is acceptable behavior. In other words, "they are doing it so I can too." Bison selfies are giving the impression that taking a picture in close proximity of a bison is a common activity, especially when there are limited negative consequences. The park is finding these norms especially hard to change and assess. Yellowstone National Park has many warning signs about dangerous animals and regulations about how close to view wildlife. However, it is these visual cues of people taking selfies and not getting hurt that are sending mixed messages about the real dangers of bison. Although these bison selfies might seem normal, there is a very real possibility that a bison-related injury could happen to you. So practice phrases such as "give them room, use your zoom" and stay back at least 25 feet for bison.