Last updated: November 2, 2017

Article

Bison Bellows: A Bottleneck of Bison

NPS Photo.

By the beginning of the 1900s, bison were not only teetering on the edge of extinction, but they were also about to endure the ultimate genetic ordeal. Think about the basic genetics you may have learned in school and every vocabulary term you needed to memorize. Bison were about to be put to the ultimate test. They entered an incredibly narrow "genetic bottleneck" with a "founding population" of perhaps a thousand individuals, suffered "inbreeding depression," "hybridization" with cattle, "isolation" from other herds, and "artificial selection." If these words are not familiar to you and seem like jargon, please consider that the combination and application of these terms to a wildlife species can ultimately be lethal. Indeed, without intervention, this is a textbook example of a species that could have been doomed.

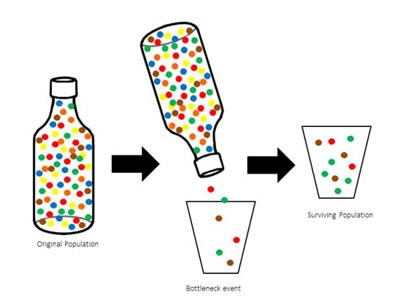

A genetic bottleneck occurs when a population is reduced to a very small subset of the original larger population, so that the last remaining individuals represent the remaining subset of the genetic heritage of the entire initial population. Certainly, the remaining individuals often do not represent the total overall genetic diversity of the population before the bottleneck.

To illustrate the point, visualize a bottle full of 100 different colored M&Ms representing genes: yellow, blue, green, red, orange, and brown. Now shake the bottle until ten M&Ms fall out. Instead of the rainbow assortment you had in the initial bottle, you now only have 5 greens, 3 browns, and 2 reds. All the M&Ms with the yellow, blue, and orange genes didn't make it through the bottleneck event, so those genes are lost forever. This happened with the bison population when their numbers fell from approximately 40 million individuals to a mere 1,000 individuals within the 19th century. Much of the original genetic diversity from the roughly 39,999,000 bison that didn't survive the bottleneck was lost for all time, leaving potentially only 1/4th of 1/100th of 1 percent remaining of the thousands of years of evolution of the American bison species.

Bottlenecks are detrimental to the viability of a species because of the loss of genetic diversity and the potential risk for inbreeding and the expression of recessive genetic traits. Inbreeding can ultimately reduce a population's fitness or the ability to survive, find mates, and reproduce. The more genetically diverse a population is, the better equipped it is to tackle the normal range of variation in survival and mortality as well as the periodically high mortality events that could arise from harsh winters or disease.

But somehow, even with the greatly reduced genetic odds, bison have survived and continue to thrive both in wild herds and in domestic production herds. Some geneticists believe that this is because the last bison survived in multiple geographically diverse areas from amongst the historic range, that the bottleneck retained important "adaptability" genes from across the historic range, and new genetic variation may have been introduced through some early 20th century efforts to hybridize captive bison with domestic cattle (although most would argue this was ultimately detrimental to the wild species). For the future, continued conservation of the bison genetics that survived the 19th century as well as protecting the opportunities for continuing wild bison evolution, remains a high priority for the ultimate recovery of the wild bison.

Did you know?

Genetic studies indicate that bison and the ancestors of domestic cattle diverged two million years ago. Hybridization that results in one sex being absent, rare, or sterile, suggests evolutionary incompatibility between the two species. Bison-cattle hybrids virtually always result in female offspring and no viable male offspring, and thus any further hybridization between bison and cattle is not a good idea for wild bison conservation!