Last updated: October 7, 2021

Article

Birthday Greetings

©George Jacobi 2018

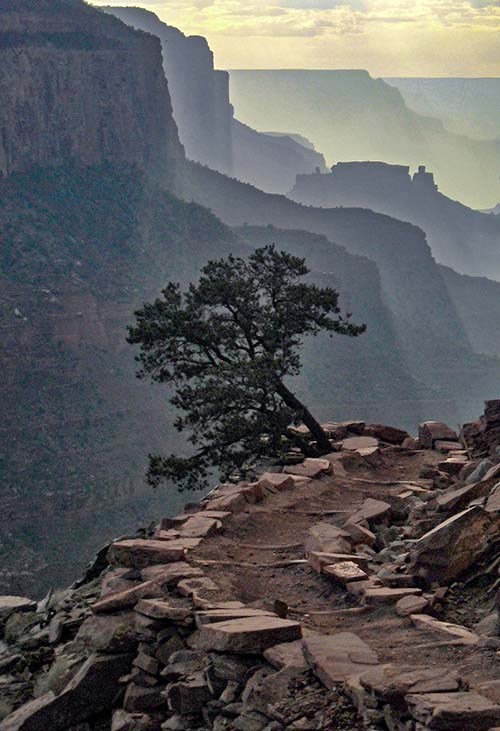

These jagged ‘waves’ bear tidings of rough weather, a faraway storm somewhere past the limits of our imperfect vision. The storm has continued for eons, bringing this infinitely slow ocean of sunlit stone to the exact evening moment we see. From the Kaibab Plateau, without a sound, these ponderous rollers of rock come in. Each rigid, motionless wave looks poised to break.

It’s a mirage. There is equilibrium here. With each gentle breath of air, millions of mineral grains slide off the crest of each wave and tumble down its trough. This is not metaphorical. Every thunderstorm, every snowmelt, every footstep wears more infinitesimal particles of limestone, sandstone, and shale from perches atop high combers, which then pour down the face of each wave and are carried by the outgoing tide of silt toward the Gulf of California.

Appearing fixed, Grand Canyon National Park is in fact in continuous motion. This dramatic landscape, to our eyes composed and dignified, is nonetheless as ephemeral as the ripples of sand on a beach. Want to watch? You’ll need to look carefully. Get down on your belly at the edge of the Rim with the ants and the lizards. When it itches and you smell the dust, you’re probably just close enough to see it happening.

Right now in downeast Maine, almost three thousand miles from here, the Atlantic Ocean crashes endlessly into the pink granite of Schoodic Point and Thunder Hole. Motion is dizzying; the roar constantly repeats itself. Yes, these are real waves, cold and indisputable. Look straight down the 75 foot precipice of Otter Cliffs, watch the white flash of a diving Eider Duck as it disappears into roiling aqua depths, and your sweaty hand will grip the guard rail tightly.

Relentless hydrodynamic action links Acadia National Park’s mountains to the sea. Fog and rain drip down the needles of firs, fall into innumerable rivulets, tumble forever into streams that don’t slow until they become marshes and tide pools and Somes Sound, the only fjard on the east coast. Ceaseless swells pummel the shore; the ancient rocks yield grudgingly.

Grand Canyon encompasses 1, 217, 262 acres, almost 2 thousand square miles. Two hundred and seventy seven miles long, the canyon would stretch from Acadia almost to New York City. The view from its overlooks includes much of the arid surrounding area as well, from the Hopi Mesas to Mt. Humphreys.

At 49,000 acres Acadia is tiny in comparison. Some of the park is on a separate headland across the bay, some is on another island 20 or more miles away. Pieces of private land still exist within its boundaries. Acadia, though, doesn’t feel small. The rocky summits, thick forests that hide most human development, and the almost always visible ocean, create a joyous sensation of boundlessness.

Both parks, among the most visited (Grand Canyon is 2nd, Acadia is 8th), are challenged by their popularity as well as continuously tested by budget issues. Commercialism in many forms grows both blatantly and surreptitiously around and within each National Park. Dedicated rangers work long hours to maintain each place unimpaired, yet open to public recreation. Volunteers like those affiliated with the Grand Canyon Association or the Friends of Acadia are both ubiquitous and crucial. Above the coves and cliffs, above the towers and temples, the night sky itself is now protected. One can actually see the Milky Way shine from horizon to horizon, reminding us of our insignificance.

What does one day matter? One moment? There will come an age when implacable seas push north up the Grand Staircase into Utah, and salt water again drowns plateau after plateau. Real waves will wash over Ooh-Aah Point and Hermit’s Rest and Temple Butte. There may not be any human eyes around then to see them. El Tovar Hotel will be history. Manhattan Island will be legend. Oil will be gone; coal and natural gas will be gone. Wind and water will remain, still carving exquisite shapes from bedrock.

Another future will inevitably arise in which Cadillac Mountain’s summit again pokes above a river of ice. Loose boulders the size of ships will scrape striations southeast toward the site of Blackwoods Campground, while hidden in a glacier a mile deep. You could walk from Bar Harbor to Nova Scotia on that ice, but you (and I) will be long gone. That’s ok. We save precious places for our own benefit and that of the few generations we can imagine following us.

We work for our children, fight and vote (and write) for our children, so that the earthly beauty that inspires us will be there to offer them the same message it brings us today. Nature addresses us all the time. Our National Parks are the very environs in which she is at her most eloquent; she speaks here not in everyday language but rather sings to us –in epic poetry set to music. That’s why they are special. We celebrate the concurrent birthdays of two places that unite America and the vision of her leaders ninety-nine years ago.

Someday we’ll all be gone–perhaps with a puff of solar wind–and the Milky Way will spin on into the endless future. So what? Let’s act today so that those parts of earth that touch our souls will remain. Today matters. Birthday greetings!