Last updated: September 20, 2019

Article

How Much Did a Beaver Hat Cost?

NPS Photo / Cassie Anderson

By Tom Holloway, Volunteer-in-Parks, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

One of the most frequently asked questions we receive at Fort Vancouver is "How much did a beaver hat cost back then?" The answers include, "It's complicated," or "It's hard to tell," or "We don't really know." The most common answer is probably some version of "a lot." So, how much was "a lot"?

Some very expensive hats may have been made for very wealthy customers who were into conspicuous consumption. But if what was commonly called a "fine beaver hat" had been only a luxury item for the super-rich, logic suggests that the fur trade as we know it would not have been sustained on such a large scale, first in Northern Europe, and then in North America, over some two and a half centuries (from about 1600 to 1850).

A better answer is something like this: "A fine beaver hat was a considerable expense, and it was a sign of a certain social status to wear one, so it was limited mainly to gentlemen of the middling and wealthy classes. All men wore a hat as part of their outdoor attire, and most men in white-collar professions, including clerks, merchants, property owners, those in the educational, technical, medical, legal, and political professions, could probably afford a beaver hat."

How do we know this? Here's some historical evidence.

One way to understand the cost of a beaver hat is to compare known prices to the cost of other typical items of consumption. Retail prices and incomes in the remote past are notoriously difficult to come by, because no centralized or standardized records were kept. Even when newspaper advertising became more common in the 1800s, most print ads did not include prices. There are many hints, however, to support the "better answer" above.

A detailed study of daily life in London, England, in the 1770s lists these typical prices:

(Source: Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson's London, [New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002] p. 296)

The price of a fine beaver hat was more than two times the weekly wage of an unskilled laborer, and the same as one week's pay for a skilled artisan (the silversmith). But a pair of fine velvet knee breeches cost much more than a beaver hat. Add a pair of silk stockings, and a man about town had spent 47 shillings to cover his legs, versus 21 shillings for a fine beaver hat to cover his head.

Moving into the period when Fort Vancouver was the active hub of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest (1825-1846), print advertisements scattered in time and space provide clues.

One of the most frequently asked questions we receive at Fort Vancouver is "How much did a beaver hat cost back then?" The answers include, "It's complicated," or "It's hard to tell," or "We don't really know." The most common answer is probably some version of "a lot." So, how much was "a lot"?

Some very expensive hats may have been made for very wealthy customers who were into conspicuous consumption. But if what was commonly called a "fine beaver hat" had been only a luxury item for the super-rich, logic suggests that the fur trade as we know it would not have been sustained on such a large scale, first in Northern Europe, and then in North America, over some two and a half centuries (from about 1600 to 1850).

A better answer is something like this: "A fine beaver hat was a considerable expense, and it was a sign of a certain social status to wear one, so it was limited mainly to gentlemen of the middling and wealthy classes. All men wore a hat as part of their outdoor attire, and most men in white-collar professions, including clerks, merchants, property owners, those in the educational, technical, medical, legal, and political professions, could probably afford a beaver hat."

How do we know this? Here's some historical evidence.

One way to understand the cost of a beaver hat is to compare known prices to the cost of other typical items of consumption. Retail prices and incomes in the remote past are notoriously difficult to come by, because no centralized or standardized records were kept. Even when newspaper advertising became more common in the 1800s, most print ads did not include prices. There are many hints, however, to support the "better answer" above.

A detailed study of daily life in London, England, in the 1770s lists these typical prices:

| Item | Cost in Shillings |

| Knee breeches, velvet | 30 |

| Hat, fine beaver | 21 |

| Weekly wage, journeyman silversmith | 21 |

| French lessons, 12 sessions | 21 |

| Wine, Portuguese, 12 bottles | 21 |

| Barometer, brass | 18 |

| Wig, public office clerk's | 18 |

| Stockings, silk men's | 17 |

| Weekly wage, unskilled laborer | 9 |

(Source: Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson's London, [New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002] p. 296)

The price of a fine beaver hat was more than two times the weekly wage of an unskilled laborer, and the same as one week's pay for a skilled artisan (the silversmith). But a pair of fine velvet knee breeches cost much more than a beaver hat. Add a pair of silk stockings, and a man about town had spent 47 shillings to cover his legs, versus 21 shillings for a fine beaver hat to cover his head.

Moving into the period when Fort Vancouver was the active hub of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest (1825-1846), print advertisements scattered in time and space provide clues.

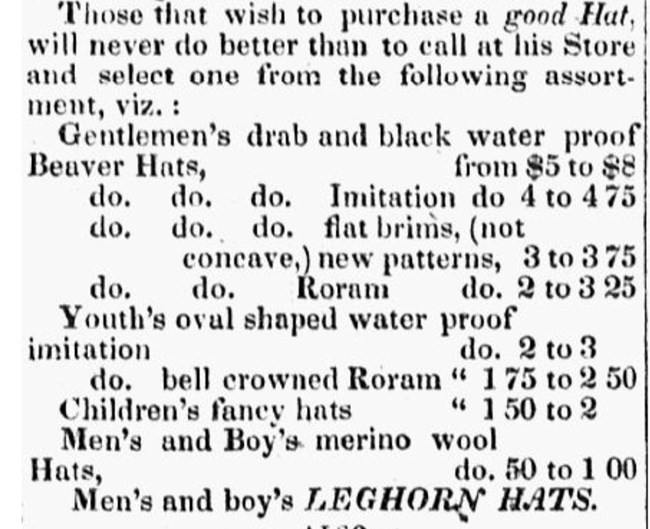

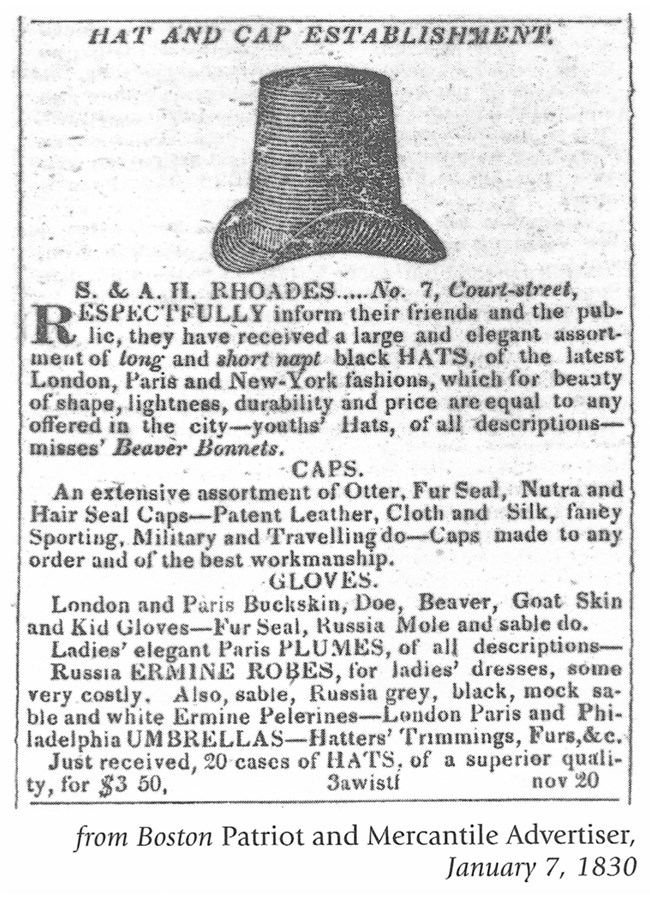

This ad from Boston's Patriot and Mercantile Advertiser, dated January 7, 1830, sold beaver hats for $3.50.

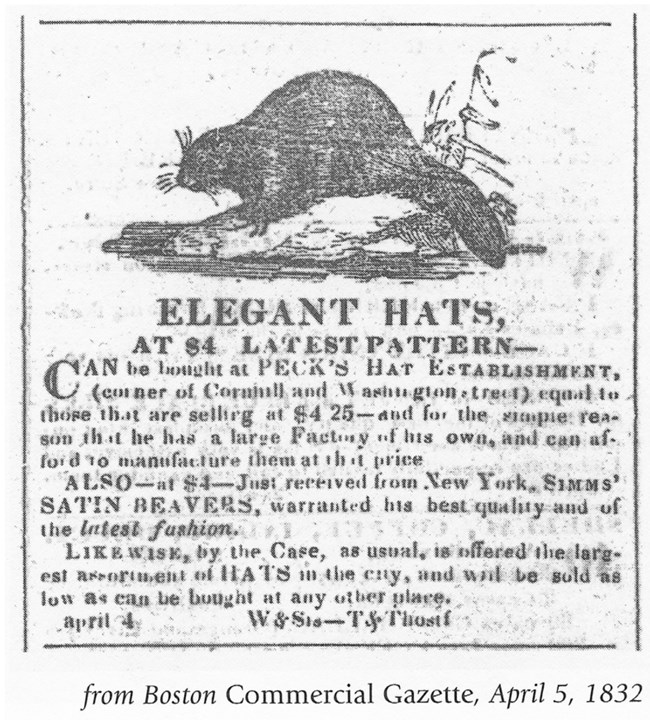

This ad from Boston's Commercial Gazette, dated April 5, 1832, sold hats for $4.00 to $4.25.

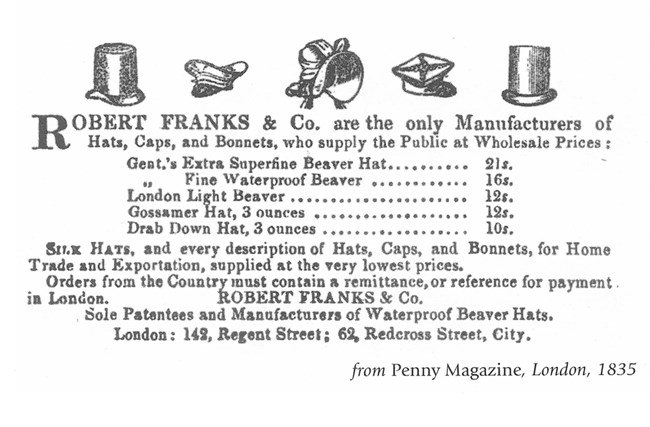

This ad, from London in 1835, offered a "Gentlemen's Extra Superfine Beaver Hat" for 21 shillings (equal to $4.67 at the time). A "Fine Waterproof Beaver" hat cost 16 shillings ($3.56), and a "London Light Beaver" hat cost 12 shillings ($2.67).

This ad from the New Bedford, Massachusetts, Mercury, dated November 20, 1840, offered a "splendid" black beaver hat for $5.00.

This ad from the Boston Daily Atlas, dated April 11, 1846, offered "Fine Beaver Hats" for $4.25.

The use of the term "wholesale prices" in these advertisements was marketing hype. Since they were individual items being sold to the general public, these were, in fact, retail prices.

The "moleskin" hats listed in this ad and the one above were silk hats with a short brushed knap. This indicates that in this period, silk hats were being sold alongside beaver hats. The lower price may help account for their increasing popularity in this period, over the more expensive beaver hats.

Data gathered by the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor provide comparisons of wages and prices over time, but coverage is spotty for earlier periods. For men's hats, the high-end prices were:

Those figures are generally in line with the prices for fine beaver hats in the print ads above. The high-end price for a pair of men's shoes was more consistent at about $2.00 over the 1825-1846 period, roughly half the price of a fine hat. Over the same period, the daily wage for a common laborer was about $1.00 per day, and the daily wage of a semi-skilled tradesman such as a blacksmith or carpenter ranged from $1.25 to $1.75 per day. (Source: Carroll D. Wright, Comparative Wages, Prices, and Cost of Living, Boston: Wright and Potter, 1889, p. 47-80)

One source of information on the price of a beaver hat is closer to home. The Hudson's Bay Company [HBC] did not make hats, but it did sell them, along with other items that provide points of comparison. Each spring, the HBC inventoried supplies on hand at Fort Vancouver, recording the wholesale price on which retail prices were based. This table shows the retail price of selected items in stock in spring 1844, ranked by value:

(Source: "Inventory of Sundry Goods, property of the Hon. Hudson's Bay Company, remaining on hand at Fort Vancouver Depot, Spring 1844," Hudson's Bay Company Archives, B.223/d/155)

A "superfine beaver hat" was an expensive item, costing not much less than a flintlock gun. But a pair of fancy cashmere pants cost even more, and three pair of regular trousers, or four cotton shirts, would cost more than the best beaver hat. The "plated beaver" hats used less expensive material for the hat body, with beaver fur glued onto the surface. They were less than half the cost of the "superfine" model. And felt hats made of sheep's wool cost much less.

In this period, the annual salary of a rank-and-file HBC laborer was £17. At the exchange rate the Company used (4s/6d = 54 pence = $1.00, or £1 = $4.44), that was equal to $75.56 per year, or $1.45 per week. The retail price of a superfine beaver hat, $8.67, was equal to six weeks' salary for a laborer. For a senior clerk making £150 per year, equal to $666.00 at the time, or $12.81 per week, a superfine beaver hat cost the equivalent of six days' salary.

Shortly after this inventory, in 1845-1846, two British Army lieutenants, Mervin Vavasour and Henry Warre, conducted a reconnaissance of the Columbia District to assess military needs in the event that boundary negotiations between the United States and Great Britain broke down. They traveled openly, but in the guise of civilian gentlemen seeking adventure. To play that role, they needed proper attire, and while visiting Fort Vancouver they acquired clothing and supplies paid for by the HBC at full retail, quoted in dollars. This table shows selected items from Lt. Vavasour's bill, ranked by value:

(Source: Joseph Shafer, "Documents Relative to Warre and Vavasour's Military Reconnaissance in Oregon, 1845-46," Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, 10:1 [Mar. 1909], 96.)

The cost of a frock coat was nearly three times that of the superfine beaver hat, which cost less than the buckskin trousers, and somewhat more than the pair of tweed pants. The four cotton shirts Lt. Vavasour bought came to $9.60, more than his superfine beaver shirt.

| Year | Beaver hat cost |

| 1825 | $5.00 |

| 1833 | $6.00 |

| 1839 | $3.50 |

| 1841 | $4.00 |

| 1844 | $3.50 |

| 1845 | $4.50 |

Those figures are generally in line with the prices for fine beaver hats in the print ads above. The high-end price for a pair of men's shoes was more consistent at about $2.00 over the 1825-1846 period, roughly half the price of a fine hat. Over the same period, the daily wage for a common laborer was about $1.00 per day, and the daily wage of a semi-skilled tradesman such as a blacksmith or carpenter ranged from $1.25 to $1.75 per day. (Source: Carroll D. Wright, Comparative Wages, Prices, and Cost of Living, Boston: Wright and Potter, 1889, p. 47-80)

One source of information on the price of a beaver hat is closer to home. The Hudson's Bay Company [HBC] did not make hats, but it did sell them, along with other items that provide points of comparison. Each spring, the HBC inventoried supplies on hand at Fort Vancouver, recording the wholesale price on which retail prices were based. This table shows the retail price of selected items in stock in spring 1844, ranked by value:

| Item | Cost |

| Coat, full dress regimental | $16.89 |

| Trousers, superfine cashmere | $11.56 |

| Gun, common Indian, 3 1/2 ft. barrel | $9.78 |

| Hat, superfine beaver | $8.67 |

| Capot, common cloth | $5.07 |

| Hat, plated beaver | $4.00 |

| Trousers, cloth | $3.15 |

| Shoes, men's | $2.88 |

| Blanket, 3-point | $2.44 |

| Shirt, men's white cotton | $2.22 |

| Hat, fine wool felt | $2.00 |

| Vest, cloth | $1.56 |

| Hat, common wool felt | $1.22 |

(Source: "Inventory of Sundry Goods, property of the Hon. Hudson's Bay Company, remaining on hand at Fort Vancouver Depot, Spring 1844," Hudson's Bay Company Archives, B.223/d/155)

A "superfine beaver hat" was an expensive item, costing not much less than a flintlock gun. But a pair of fancy cashmere pants cost even more, and three pair of regular trousers, or four cotton shirts, would cost more than the best beaver hat. The "plated beaver" hats used less expensive material for the hat body, with beaver fur glued onto the surface. They were less than half the cost of the "superfine" model. And felt hats made of sheep's wool cost much less.

In this period, the annual salary of a rank-and-file HBC laborer was £17. At the exchange rate the Company used (4s/6d = 54 pence = $1.00, or £1 = $4.44), that was equal to $75.56 per year, or $1.45 per week. The retail price of a superfine beaver hat, $8.67, was equal to six weeks' salary for a laborer. For a senior clerk making £150 per year, equal to $666.00 at the time, or $12.81 per week, a superfine beaver hat cost the equivalent of six days' salary.

Shortly after this inventory, in 1845-1846, two British Army lieutenants, Mervin Vavasour and Henry Warre, conducted a reconnaissance of the Columbia District to assess military needs in the event that boundary negotiations between the United States and Great Britain broke down. They traveled openly, but in the guise of civilian gentlemen seeking adventure. To play that role, they needed proper attire, and while visiting Fort Vancouver they acquired clothing and supplies paid for by the HBC at full retail, quoted in dollars. This table shows selected items from Lt. Vavasour's bill, ranked by value:

| Item | Cost |

| Coat, frock | $26.40 |

| Trousers, buckskin | $9.12 |

| Hat, superfine beaver | $8.88 |

| Trousers, tweed | $6.48 |

| Shoes, blucher | $3.72 |

| Vest, Valencia | $3.36 |

| Shirt, white cotton | $2.40 |

(Source: Joseph Shafer, "Documents Relative to Warre and Vavasour's Military Reconnaissance in Oregon, 1845-46," Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, 10:1 [Mar. 1909], 96.)

The cost of a frock coat was nearly three times that of the superfine beaver hat, which cost less than the buckskin trousers, and somewhat more than the pair of tweed pants. The four cotton shirts Lt. Vavasour bought came to $9.60, more than his superfine beaver shirt.

Photo: Joe Blanco

Conclusions

These scattered pieces of evidence support the conclusion that a beaver hat, whether "superfine" or of a lesser quality (plated or roram), was a common accessory for gentlemen of means and status, available at prices in line with other items of wardrobe. This is especially true if we consider that a good hat, well cared for, would last several years. For men of the laboring classes, however, such a hat would have not only been an extravagance, but also not in keeping with their station in life.

Rather than think of a beaver hat as a very expensive luxury item for the few, it might be appropriate to compare it to something that in more recent times has differentiated the daily attire of men in the blue collar ranks from those in white collar occupations - a suit and tie. A man's business suit involves considerable expense, but also represents a certain social status, and its use has been both common and widespread in certain circles. So too with the beaver hat, in former times.