Last updated: April 14, 2023

Article

Attu: North American Battleground of World War II

Courtesy Elmendorf Air Force Base History Office, Alaska

In early June 1942, Americans had cause both for jubilation and for despair. As they tuned in their radios for news of the war, they heard of the coordinated attacks by the Japanese on the Midway and Aleutian islands. At the Battle of Midway, American planes sunk four Japanese aircraft carriers and destroyed or damaged some 300 planes. But in the Aleutians, the Japanese bombing had been successful, and Japanese forces occupied the islands of Attu, Agattu, and Kiska. This alarmed the American people because it was feared that the enemy would use Attu and other small Aleutian islands as a staging area for attacks on the North American mainland. There was also concern that the occupation might disrupt United States-Siberian communications necessary for the Lend-Lease program, a program allowing the president to sell, transfer, exchange, lend equipment to any country to help it defend itself against the Axis powers. This included assistance to the U.S.S.R. The Americans had to regain the Aleutians at all costs. Following a difficult campaign, made more difficult by the weather, the Americans did oust the Japanese from Attu and gain control of the rest of the Aleutians. The islands then were used as a staging point for attacks on Japanese territory.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file for "Attu Battlefield and U.S. Army and Navy Airfields on Attu" (with photographs) and other source materials. Attu was written by Fay Metcalf, education consultant. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in U.S. history, social studies, and geography courses in units on World War II. Attu will help students understand the indomitable spirit of soldiers on both sides of World War II fighting for what they believed to be a just cause.

Time period: World War II

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

- Standard 3B- The student understands World War II and how the Allies prevailed.

- Standard 3C- The student understands the effects of World War II at home.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

- Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

- Standard C - The student uses appropriate resources, data sources, and geographic tools such as aerial photographs, satellite images, geographic information systems (GIS), map projections, and cartography to generate, manipulate, and interpret information such as atlases, data bases, grid systems, charts, graphs, and maps.

- Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme IX: Global Connections

- Standard B - The student analyzes examples of conflict, cooperation, and interdependence among groups, societies, and actions.

Objectives for students

1) To explain how the Japanese occupation and American recapture of Attu were significant in the history of World War II.

2) To describe the complexity of even a relatively small-scale military campaign.

3) To discuss both the valor of the American soldiers, who fought under weather conditions considered among the worst in the world, and the loyalty of the Japanese troops to their emperor and their cause.

4) To analyze different sources of information relating to a particular historic site.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-quality version.

1) one map of Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands;

2) one reading about the Battle of Attu;

3) one drawing of the battle;

4) six photos of the battle and its aftermath.

Visiting the site

Attu is in a very remote and inaccessible location and military clearance is required to visit it. More information is available from the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Aleutian Islands Unit, PO Box 5251, Adak, Alaska, 99546 or Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, 95 Sterling Hwy #1, Homer, AK 99603.

Aleutian World War II National Historic Area is located on Amaknak Island in the Aleutian Island Chain, 800 miles west of Anchorage, the nearest large urban center. It can be reached by air through commercial and charter flights from Anchorage, or by the Alaska Marine Highway (Ferry System). The park is open year around. The best time to visit is May through October. For more information, write to Ounalashka Corporation, P.O. Box 149, Unalaska, AK 99685, or visit the park's Web page.

Getting Started

Inquiry Questions

How would you describe the terrain?

What might the indentations in the ground be?

What could they be used for in a time of war?

Setting the Stage

The Aleutian Islands form a 1,000-mile chain of islands that arc westward from Alaska. In 1867 the United States acquired the islands, along with Alaska, from Russia. The island chain that includes the Aleutians continues for another 300 miles to the west. These western islands, called the Komandorskis (or Commander Islands), are close to the Kamchatka Peninsula and were part of the Soviet Union in 1942. Although there were bombing raids on other Aleutian islands during World War II, Attu, the western most island of the U.S.-held chain, was the site of the only land battle on the North American continent during World War II.

Like the rest of the Aleutians, Attu is composed of volcanic mountains and tundra valleys. The island is approximately 40 miles long and 20 miles wide. Its highest peak rises more than 3,000 feet above sea level. Located between the frigid Bering Sea and the warm Japanese Current of the North Pacific Ocean, the island's waters remain free of ice, but the area is subject to year-round, vicious wind storms known as williwaws, and dense, impenetrable fogs. It rains or snows an average of 200 days a year. During the spring--when the battle of Attu was fought--temperatures generally hover around freezing (32º F). Glaciers and snow drifts mark the higher elevations, and lower levels support only spongy tundra and low-growing plants.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate the Aleutian Islands in an atlas or on a large-scale map of the Pacific Ocean. Determine the names of the two closest large land masses.

2. On your atlas or map, also note the location of the Aleutians relative to the coast of Japan, as well as their relationship to the mainland of the United States. Does this give you a sense of how remote Attu is?

3. How would this location determine the climate of the island?

4. Now examine Map 1 carefully. What is the distance between Attu and the Alaskan mainland?

5. How might the military transport troops and supplies to Attu? How difficult do you think this might be?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Attu Battlefield and U.S. Army and Navy Airfields on Attu

Japan's plans for the Aleutians called for a carrier air attack on Dutch Harbor and Fort Mears and a hit-and-run assault on Adak Island (which Japan erroneously believed to be fortified) further out on the chain. By means of a separate naval task force, the Japanese also planned the occupation of Kiska and Attu at the end of the Aleutians. The air attacks on Unalaska occurred June 3 and 4, coinciding with the Battle of Midway. When the magnitude of their naval defeat became clear, the Japanese canceled the raid on Adak, but proceeded with the invasions of Kiska and Attu; both were occupied on June 7.

While Japanese naval troops secured Kiska, the Japanese army landed on Attu. The 1,140-man force consisted of infantry engineers, and a service unit, under the command of Maj. Matsutoshi Hosumi. The Aleuts and their teacher were taken prisoner and eventually removed to Japan. The teacher's husband lost his life in unclear circumstances. At first the Japanese planned to hold the islands only until the onslaught of winter, but soon decided to remain in the Aleutians so as to deny the enemy use of the islands. In mid-August the commander concluded that the Americans were preparing to invade Kiska and decided to move the Attu garrison to that island.

Attu remained unoccupied until the end of October, when fresh troops, including the 303rd Independent Infantry Battalion, arrived from Japan. In April 1943 Col. Yasuyo Yamasaki came by submarine and took command of Attu's growing defenses and partially completed airfield. Despite some increase in American air attacks from newly constructed forward bases (Adak, September 1942; Amchitka, February 1943) and stepped-up American naval activity, Japan succeeded in reinforcing its Aleutian outposts with troops, armament, and supplies until March 1943.

Battle of Komandorski Islands

Determined to interdict Japanese convoys en route to the Aleutians, an American naval task force, led by heavy cruiser Salt Lake City, arrived off the Soviet Union's Komandorski Islands west of Attu. On March 26, the ships' radar picked up a column of eight Japanese warships and two transports carrying supplies for the Aleutians. Both sides opened fire simultaneously and there ensued "an old-fashioned long-range ship-to-ship duel that lasted almost four hours."¹ Although each scored hits, the battle ended inconclusively when both forces withdrew. The Americans could savor one aftereffect, however: the Japanese transports hurried home and Japan made no further attempt to reinforce or resupply the Aleutians with surface vessels. From then until the American invasion in May only submarines succeeded in delivering a trickle of materiel to Attu and Kiska.

Recapture

By early 1943, American planning for the recapture of Kiska had begun in earnest. The army's 7th Infantry Division was chosen as the landing force and trained in amphibious warfare under U.S. Marine Corps Maj. Gen. H. M. "Howling Mad" Smith.² In March, however, sufficient naval power was not available to assault the more heavily defended Kiska. In addition, the Japanese were expecting an attack on Kiska. A successful assault on Attu would isolate the Japanese on Kiska between American bases on Attu and Adak and would make Kiska easier to capture. American planners therefore decided to undertake an operation against Attu.

The assault date was set for May 7, 1943, under the command of R. Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, North Pacific Force, with R. Adm. Francis W. Rockwell in charge of the amphibious phase and Maj. Gen. Albert E. Brown, 7th Division, assuming command when the troops were established on shore. The battleships Pennsylvania, Idaho, and Nevada provided fire support.

Bad weather postponed the landings until May 11 when both the Northern and Southern Landing Forces headed for shore. The Northern landing took place as planned. At Austin Cove on Attu's north shore, a provisional battalion landed and began a torturous ascent to the passes west of Holtz Bay--a five-day ordeal resulting in many cases of frostbite. At Red Beach, on the northwest shoulder of Holtz Bay a battalion of the 17th Infantry Regiment and a party of Alaskan scouts landed unopposed. These forces were soon joined by a battalion of the 32nd Infantry Regiment and together the forces drove south toward the Japanese positions at the head of Holtz Bay.

At Massacre Bay fog delayed the landing of the Southern Force, consisting of two battalions of the 17th Infantry Regiment, until late afternoon. They too, were unopposed. The Japanese had placed their defenses on the ridges surrounding upper Massacre Valley and were hidden by the fog. By evening, however, both the Northern and Southern forces had come under Japanese fire. By May 13, it was apparent that fierce Japanese resistance had stalemated the Southern Force's advance. The Northern Force was also making slow progress against a stubborn foe. The remainder of the 32nd Infantry Regiment landed that day at Massacre Bay. Later, Alaska's defense force, the 4th Infantry Regiment, also joined the fight. Admiral Kinkaid, convinced that General Brown was bogged down, relieved him and appointed Army Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum to take command on Attu.

For a full week the Japanese prevented the Northern and Southern forces from joining in Jarmin Pass. Then the Japanese began withdrawing slowly toward Chichagof Harbor and its surrounding ridges. Two more weeks of bitter fighting occurred before the 7th Division and its reinforcements succeeded in driving the enemy from the snow-covered cliffs of Fishhook Ridge and Clevesy Pass, which opened the way to Chichagof.

On the night of May 29, the 1,000 surviving able-bodied Japanese made a screaming banzai attack out of Chichagof Harbor, up Siddens Valley toward American positions in Clevesy Pass and against Engineer Hill, killing and being killed. Engineer troops bivouacked on Engineer Hill succeeded in organizing a thin defensive line and breaking the attack. The next morning, May 30, Japan announced the loss of Attu. For many days thereafter, however, American forces continued mopping-up operations.

Casualties were heavy on both sides. Out of a force of about 2,500, only 29 Japanese survived. Of the 15,000 U. S. troops, 550 died and 1,500 were wounded. Another 1,200 Americans were casualties of Attu's climate. Inadequate footgear, in particular, contributed to frozen feet and trenchfoot.

Almost immediately, army engineers and naval seabees began constructing airfields on Attu. Rejecting the Japanese runway at East Holtz Bay as unsatisfactory, army engineers completed a fighter field at West Holtz (Addison Valley) and another on Alexai Point. The latter was soon extended to serve bombers as well.

On July 10, 1943, the 11th Air Force made its first attack on Japan's Home Islands. Eight B-25 bombers flew from Attu to strike Paramushiro in the Kuriles. This was the first air attack on Japan since the famous Doolittle raid of April 18, 1942.

Other attacks followed. Most met with some success until September 11, 1943, when a force of 12 B-25 medium bombers and eight B-24 heavy bombers left Attu for Paramushiro. On this occasion, Japanese fire destroyed three bombers. Another seven were heavily damaged and forced to land in Siberia where the crews were interned. Although further raids were postponed for several months, Attu's bombers were again over the Kuriles by spring 1944.

The navy constructed both land runways and a seaplane base for patrol bombers and flying boats west of Massacre Bay and at adjacent Casco Cove. For the duration of the war, naval aircraft made their lonely patrols over the North Pacific. As at Alexai Field, the navy's two land runways were first covered with steel (Marston) mats. By 1944, however, asphalt had been laid and the navy made the runways available to army planes as well as its own, and the 11th Air Force established maintenance facilities there.

As for the Attuan Aleuts, about half of them died while in Japan, mostly from tuberculosis. After Japan's surrender, the survivors, along with the teacher, Mrs. Charles Foster Jones, returned to the United States. Too few in number to begin anew on their island, the Attuans resettled on Atka Island in the Aleutians, together with the inhabitants of that place. The Attuans have not forgotten their homeland. Nor have veterans of the "Forgotten War"--Japanese or American--let Attu slip from their memories.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How long did the Japanese occupy Attu?

2. Why did the Japanese stop carrying supplies to Attu by transport ship?

3. How long did the American assault on the island take?

4. What effect did weather have on the battle?

5. What event marked the end of the battle?

6. How many casualties were there on each side? How many American soldiers succumbed to the weather?

7. Describe American activities on the island following the battle.

Reading 1 was compiled from Erwin N. Thompson, "Attu Battlefield and U.S. Army and Navy Airfields on Attu" (Aleutian Islands) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984.

¹Paul S. Dull, A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941-1945) (Annapolis, 1978), p. 261.

²General Smith witnessed the 7th Infantry Division's amphibious assault on Attu and wrote, "I have always considered the landing...in the dense fog of Attu...an amphibious landing without parallel in our military history." Holland M. Smith and Percy Finch, Coral and Brass (Washington, 1979), p. 103.

Visual Evidence

7th Infantry Division, 11 May 1943.

Adapted from Stetson Conn, et al., Guarding the United States and Its Outposts

Questions for Drawing 1

1. Using Reading 1, locate the sites of the battle on Drawing 1.

2. What natural land features assisted the Japanese in holding back American troops for a short time?

3. Locate Siddens Valley. What made the Japanese banzai attack through here so precarious?

Visual Evidence

U.S. Army Signal Corps

E. M. Thompson

U.S. Army Signal Corps

Questions for Photos 1-3

1. Examine the three photos, paying close attention to the captions. How did the Japanese use the natural environment of Attu to defend their occupation of the island?

2. What advantages did the Japanese have over the American troops?

3. Note the date that Photo 2 was taken. What does this photo demonstrate about the effect troops had on the environment?

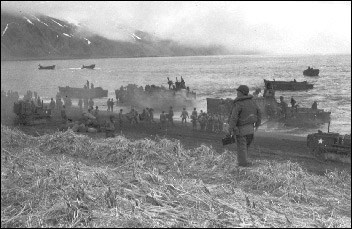

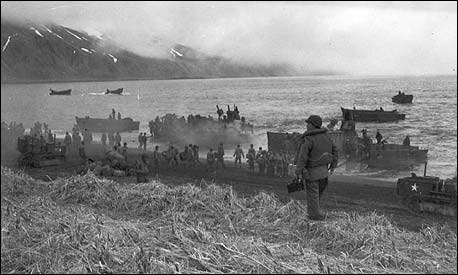

Photo 4: Seventh Infantry Division troops landing at Massacre Bay, Attu, May 1943.

Courtesy Elmendorf Air Force Base History Office, Alaska

Courtesy Elmendorf Air Force Base History Office, Alaska

Questions for Photos 4 & 5

1. Examine both photos carefully. What observations can you make about the terrain on Attu?

2. How did Attu's terrain hinder the American troops' effort to regain the island?

3. Study Photo 1. How safe do you think landing troops at Massacre Bay was? Why? What obstacles did they face?

4. Examine Photo 2. Why was it so hard to move supplies on the island?

U.S. Army Signal Corps

Note to educators: This image depicts human remains and is blurred out of sensitivity. To view the unaltered image, click on the photograph.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Refer to Reading 1 and describe what happened in Photo 6. Why would the Japanese soldiers do this?

2. Examine all six of the photos presented in Visual Evidence. How can photos help historians analyze a particular event? What are the strengths of using photos to interpret history? What are the weaknesses?

3. All of the photos in Visual Evidence, except Photo 2, were taken by military personnel as an official record of the island campaign. Can photos, by themselves, fairly represent a historical event? Why or why not?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help demonstrate to students the chronology of World War II and the context of Americans at war.

Activity 1: Setting the Context

Have the students first check their own history textbooks to see if Attu or the Aleutian Islands are mentioned. Then have them choose one of the following assignments:

-

Research the Battle of Attu more fully and make a report to the class.

-

Examine the entire war in the Pacific to better understand the particular role the Battle of Attu played in the full campaign.

-

Call veterans' groups in the community and try to arrange for members who fought in World War II to come to class and speak about their personal experiences.

Activity 2: The Local Impact of World War II

Have students investigate their own region to see how it was affected by World War II. If there were active military bases, they might find out where the armed forces who trained there were sent. They might also check to see if local factories were engaged in war work. If these bases or factories no longer exist, the students could find out what is now located on the sites. Local papers published during the 1940s are good sources both for information and photographs. These usually can be found in the archives of public libraries or in the morgue of the newspaper office. Senior citizen centers are good places to conduct interviews about how the military base or factory affected the local community. Using text and image editing software or traditional art materials, have each student design 1-3 pages to display their findings with images and text. Take the students' pages and create a class booklet on how their region experienced the War.

Activity 3: War and the Individual

Encourage students to invite a veteran of Operation Desert Storm or Operation Iraqi Freedom to visit the classroom to describe another recent military engagement where climate and logistical problems played a very large role. After the presentation, have students discuss similarities and differences between the two battles. Then ask them to write an essay on the role of the ordinary soldier (both American and Japanese) during the crisis of war.

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Attu: North American Battleground of World War II, students better understand why an isolated battle on a remote island in Alaska alarmed the nation. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

National Park Service

Aleutian World War II National Historic Area is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web pages focus on various aspects of the Aleutian experience during World War II. Included are biographies of key American and Japanese figures, chronologies, and historical photos. Also included are links to the histories of the Unangan peoples (commonly called Aleuts) and the Aleutian Islands.

American Memorial Park

American Memorial Park, a unit of the National Park System in Saipan, the largest island in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, commemorates those that gave their lives in the Marianas Campaign of World War II. Dedicated in 1995 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Invasion of Saipan, the memorial includes the names of the over 5,000 soldiers that gave their lives. Included on the park's web page is a virtual World War II Museum.

Florida State University

The Institute on World War II and the Human Experience has a tremendous online archive of newspapers, photographs, letters, cartoons, ration cards, and more that help detail the history of Americans in World War II. The program is also gathering oral histories of veterans, their spouses, and others related to the defense industry.

World War II Veterans

The World War II U.S. Veterans Web pages contain information and services for veterans of World War II. Created by Dick Berry, a World War II Navy Veteran, and his son, the site has information regarding the proposed World War II U.S. Veterans Memorial Museum, a veterans forum, as well as World War II and 1940s memorabilia. The site also features various links that may be of interest such as The Veterans Administration and The Official U.S. Military Reunion Site.

Alaska State Government

For information about the history of Alaska, the state government has compiled a chronological history from Vitus Bering's exploration of the North Pacific in 1725, to the invasion of the Aleutian Islands, to the economic and political news of 1993.

For Further Reading

Students (or educators) wishing to learn more about the Battle of Attu may want to read: Stan Cohen, The Forgotten War, vols. 1 and 2 (Missoula, Mont.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1981 and 1988); John Cloe, The Aleutian Warriors (Missoula, Mont.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1990); and Jim Reardon's fictionalized but informative Castners Cutthroats, Saga of the Alaska Scouts (Prescott, Ariz.: Wolfe Publishing, 1990). Personal accounts may also be found in The Capture of Attu, Tales of World War II in Alaska (Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Publishing Co., 1984).

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- battlefields

- world war ii

- battle of attu

- battle of midway

- aleutian islands

- military and wartime history

- 20th century

- mid 20th century

- early 20th century

- military wartime history

- u.s. in the world community

- military history

- military wartime history

- world war 2

- alaska

- twhplp