Last updated: December 5, 2023

Article

At a Crossroads: The King of Prussia Inn

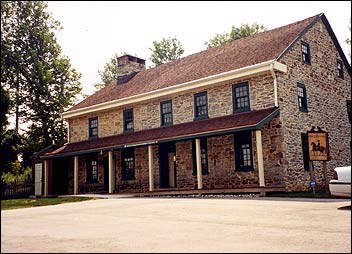

(Courtesy King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

A crowd of local residents, the press, and employees of the various agencies and contractors who had worked on the preparations started gathering at dawn. At about 9:00 a.m. the sound of the motors from the self-propelled jacks increased in volume and pitch, the crowd held its collective breath, and slowly, inches at a time, the venerable old building began to move. Traveling only feet an hour, the inn made its way up Route 202, passed safely over the culvert, to Gulph Road, where it made a right turn--with contractors soaping the tires so they could slide along the curbing and manually turning the jacks. From there the inn proceeded about a half mile to its new site.¹

Moving the King of Prussia Inn to a new location was just one of the many changes witnessed by the inn during its history. When the inn was first built in 1719, Pennsylvania was still a British colony. Though that building was but a small farmhouse, the inn later grew to a prosperous tavern and inn at the heart of a town of the same name. For more than two centuries, the King of Prussia adapted to its everchanging surroundings. In 1952, the State of Pennsylvania acquired the property for roadway improvements. For nearly 50 years, the inn sat idle until the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation accepted a plan by the King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce at Valley Forge for the relocation of the historic inn. Today the Chamber of Commerce occupies the building, and its story is preserved for generations to come.

¹ Richard M. Affleck, “At the Sign of the King of Prussia,” Byways to the Past, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2002.

About This Lesson

This lesson plan is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, King of Prussia Inn. Most of the text in the lesson was adapted from “At the Sign of the King of Prussia,” by Richard M. Affleck. This article was featured in Byways to the Past, a publication by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PENNDOT). Other information came from PENNDOT databases and files on the King of Prussia Inn. The lesson was written by Becky Knapp, an intern for PENNDOT. It was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the countryWhere it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in units relating to the life and culture of colonial America, archeology, transportation history, and settlement and use of land.

Time Period: early 18th century to late 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Era 2: Colonization and Settlement (1585-1763)

- Standard 3A- The student understands colonial economic life and labor systems in the Americas.

- Standard 2C- The student understands the Revolution's effects on different social groups.

- Standard 3B- The student understands how a modern capitalist economy emerged in the 1920s.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Theme I: Culture

- Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

- Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

- Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

- Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

- Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spacial distribution patterns.

- Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

- Standard D - The student describes a range of examples of the various institutions that make up economic systems such as households, business firms, banks, government agencies, labor unions, and corporations.

- Standard A - The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

1) Describe the historical significance of the King of Prussia Inn, including its relationship with transportation history.

2) Examine how archeology and artifacts found at the King of Prussia Inn help us better understand the people that used the inn and its use over different periods of time.

3) Outline the historic preservation efforts of federal, state, and local organizations to save the inn.

4) Research a historic inn or hotel in their community and determine its impact on the town, and understand how the town impacted the historic site.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) three maps showing the King of Prussia area and the archeological excavations done on the inn;

2) three readings regarding the history of the inn, the archeological investigation done on the property, and the historic preservation efforts undertaken to save it;

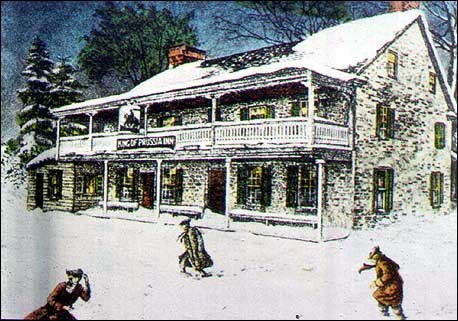

3) one painting of the inn, displaying a winter scene from the late 19th century;

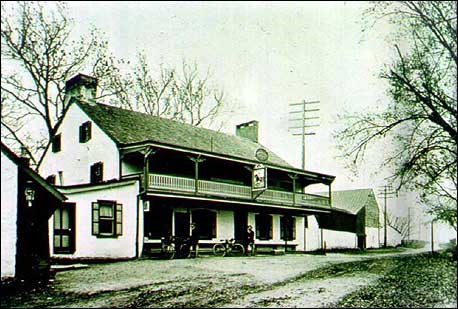

4) four photographs of the King of Prussia Inn, ca. 1910, archeology being done at the inn, and the inn being moved in 2000.

Visiting the site

The King of Prussia Inn is located in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. From Philadelphia, take I-76 West. Merge onto Dekalb Pike West and U.S. 202 North via exit 328B toward King of Prussia. Turn right onto South Gulf Road. Turn left onto Bill Smith Blvd. The inn is currently owned by the King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce. Tours of the site are given by appointment only. For more information, please contact the Chamber of Commerce at The Historic King of Prussia Inn, 101 Bill Smith Blvd., King of Prussia, PA, 19406, or call 610-265-1776, or visit their website at [http://www.kopinn.com].

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

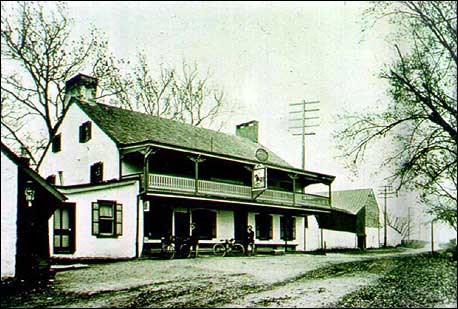

(Courtesy of King of Prussia Historical Society)

Setting the Stage

| Pennsylvania was still a British colony when the King of Prussia Inn was built in 1719 at the intersection of Swedesford and Gulph Roads. Though that building was but a small farmhouse, the house later grew to a prosperous tavern and inn at the heart of a town by the same name. For more than two centuries, the inn and farmhouse functioned with varying degrees of prosperity and fame. The inn provided hospitality to travelers when the colony was just a scattering of farms around the very young city of Philadelphia. It is likely the inn attracted traders on the road from the port of Wilmington, Delaware, who were going north to Norristown, Pennsylvania, where barges could take their goods east on the Schuylkill River to Philadelphia. It also seems likely that the crossroads--upon which the inn was built--influenced the making of this home into a tavern and inn. The King of Prussia, like other historic inns, links us to the day-to-day lives of travelers, inn keepers, and merchants; and to important trends in the commercial and social history of our country. Historic inns, like the King of Prussia, dotted the major transportation routes and were usually located at important crossroads. Their histories are very much tied to the history of the American transportation network. In the course of providing food, rest, and entertainment for generations of travelers, the inn witnessed many events, trends, and ideas that are central to American history. These included the early network of roads and turnpikes that were essential to the rise of Colonial commerce and trade; the comings and goings of armies during the American Revolution; urban and suburban growth that followed the improvement of local roads in the 19th and 20th centuries; and the rise of the modern American transportation network. After extensive efforts on behalf of preservationists and transportation officials to save this structure from encroaching suburban growth, the inn now serves as a wonderful example of the importance of preserving our past for the future. |

Locating the Site

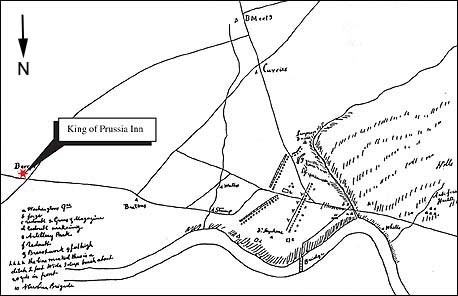

Map 1: King of Prussia Area, 1777.

(Clements Library, University of Michigan)

If needed, use a dictionary to familiarize yourself with the military terminology.

a. Washingtons Qtrs (quarters)

b. forge

c. redoubt 2 Guns & Magazine

d. redoubt makeing

e. Artillery Park

f. redoubt

g. Breastwork 4 feet high

hhhh. the line marked there is a ditch 2 feet wide 3 deep brush about 20 yds (yards) in front

10 N Carolina Brigade

This is a detailed portion of a larger map of the area surrounding Valley Forge. It was drawn by William Parker in 1777 and is referred to as a “spy map.” It is believed that Parker was spying on George Washington's forces for the British. This detail depicts the area around the King of Prussia Inn, which at the time was also known as Berry's after the proprietor, James Berry.

The horizontal road on which the inn sits is now known as Route 202. The road dates as far back as the 1680s as evident by its notation on a map of that time demonstrating the Penn family's landholdings.

Questions for Map 1

1. Inns and taverns are represented by triangles on the map. List three other taverns shown on the map.

2. Compare and contrast the locations of Barry's and the other inns you identified. What is similar about the inns' locations, and why might they be built there?

3. Closely examine the map and its key. List three places, objects, groups or landforms shown on the map besides taverns. Why might the British army be interested in this information?

Locating the Site

Map 2 shows the area around the King of Prussia Inn circa 1871. The road running horizontally across the upper half of the page is Route 202 and the road traveling diagonally from the bottom right portion of the map to the top left is Gulph Road. The inn is at the crossing of these two streets.

Questions for Map 2

1. Railroads frequently brought new people and goods into a town. With this in mind, how might the proximity of the railroad to the King of Prussia Inn have affected the inn's business?

2. The King of Prussia Inn is not noted on the map. What other industries are noted?

3. Today, the town of King of Prussia in Pennsylvania is rather large. At the time this map was drawn, however, the town is virtually nonexistent. Yet, there is some evidence on the map that a town center was beginning to form. Study the area surrounding the intersections of Gulph and Route 202. What indications are there demonstrating the beginnings of a “town center” and growing village?

Locating the Site

Map 3: Detail Archeological Excavation Map, King of Prussia, 1990s.

Map 3 depicts the detailed archeological excavation plan for the original site of the King of Prussia Inn, before the building was moved. The squares labeled as units and the gray-shaded areas labeled as features are where the excavations took place. Units are areas, usually squares or rectangles, in which archeologists dig. Features are evidence of human activities visible as disturbances in the soil. Such disturbances can be things like pits dug for storage, posts set for houses, or hearths constructed for cooking.

Questions for Map 3

1. Look at the areas of excavation. Why might the archeologists have looked for historical evidence there? Might there be a correlation between the window and door location and that of the excavation? If yes, why might artifact concentrations have been located there?

2. Note the location of the “Historic Road.” How might the proximity of a road affect the King of Prussia Inn's business?

3. Why might a fence have been erected around the inn while the excavation process took place?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The King of Prussia Inn

The history of the King of Prussia Inn begins in 1719, when William Rees, Sr. purchased 150 acres of land from his father. The Rees's, like most families in 18th-century Pennsylvania, were farmers. There is evidence that the Rees dwelling was a small, frame, two-room, 1½-story structure, typical for farmers of that period.

When William Rees, Sr. died in 1756, his estate passed to his son, William, Jr. Unlike his father, the younger William Rees was not interested in agriculture. He rented out his farmland and began a tavern business in 1769, having constructed a large new stone addition to his parent's farmhouse. William, Jr. was actively involved in running the inn for only three years, after which he turned his tavern license over to someone else. Rees died in April 1776, leaving his family in considerable debt.

By 1770, the place was referred to as “the Sign of Charles Frederick Augustus, King of Prussia.” There are several stories about how the inn received its name. One story said that the name was in reference to Frederick the Great of Prussia who assisted the British in defeating the French in the Seven Years War (known as the French and Indian War in North America). Another story said the inn was named for King Frederick the Great for his support of George Washington during the American Revolution. A third account states that a sign was hung outside the tavern honoring the German king to attract the German contingent participating in the American Revolution.

Over the years, there has been considerable speculation about the role of the inn during the American Revolution, particularly during the Valley Forge encampment. In September 1777, Sir William Howe and 15,000 British troops invaded Pennsylvania and quickly captured Philadelphia after defeating George Washington's army at the Battle of Brandywine. That winter, the Continental Army went into camp at Valley Forge, which was very close to the King of Prussia Inn. According to James Thomas Flexner, in his biography on George Washington, he made the decision to move his troops at an inn about a mile from Valley Forge.

Considering how close it was to the encampment, the assumption that Washington, his officers, and their men spent time at the inn is logical. Local tradition states that George Washington and a number of his officers ate and slept there. The inn was also reputed to have hosted British officers and loyalist spies. Masonic lodge meetings (Masons are part of a universal brotherhood of men dedicated to serving God, Family, Fellowman, and Country), presided over by Washington, are also said to have taken place at the King of Prussia Inn. There is unfortunately no documentary evidence solidly linking the inn to any of the famous names associated with Valley Forge.

The known connections between the King of Prussia Inn and the Revolution are more ordinary than what tradition passed down through the years. James Berry, who managed the business during the war, was in fact an officer in the militia, and Griffith Rees, William Jr.'s son, served as a private and was wounded in a skirmish with British forces near Darby, Pennsylvania, in October 1777.

The family struggled to keep the inn and the farm going, but to no avail. Two years after the official end of the Revolution (1783), the Rees family sold the King of Prussia Inn and surrounding farmland to John Elliot, Sr., who made a series of improvements to the property. Elliot demolished the original log or frame dwelling and constructed a 2½ story stone addition onto the east end of the building.

Elliot and his wife Sophia ran the inn and its supporting farm for the next 35 years, and it was then that the inn reached its height as a social center for the surrounding community. In addition to its role as a place of entertainment, the inn served as an informal town hall where meetings were held and as a collection point for U.S. taxes.

John Elliott, Jr. and his wife also farmed the property and operated the inn, which, by the 1860s, was known as the King of Prussia Hotel. The change in name most likely came about because of pressure from the temperance movement, which sought to restrict the consumption of alcohol. The term “hotel” served to distance the King of Prussia from its less temperate past.

James and Madeline Hoy acquired the property shortly after Elliott died in 1868. They turned the farm into an up-to-date mechanized agricultural operation. The Hoys possibly added the two-story veranda to the front of the building and the porch built onto the rear of the western half of the inn.

James Hoy died in 1886, and for the next 20 years his widow, Madeline, ran the farm and presided over the hotel. After Madeline Hoy sold the place in 1906, the King of Prussia went through a period of relatively short-term occupations until Anna Heist bought it in 1920.

Anna Heist took advantage of the American's newfound love of the automobile and interest in their colonial past, by turning the King of Prussia Inn into a modest tourist attraction. Anna Heist continued to operate the King of Prussia Inn until 1952 when the Pennsylvania Department of Highways acquired the property. Ironically, the automobile, which saved the inn from possible oblivion earlier in the century, now proved to be a threat. The rapidly growing suburbs outside of Philadelphia required improved highways, and Route 202, like many other roadways, was widened and divided to handle the increased volume of traffic.

For nearly 50 years, the inn slowly fell into a state of decay despite local efforts to perform maintenance. By the early 1990s it became clear that additional improvements to the local roadways were necessary to ease traffic congestion and improve safety. Such improvements would clearly impact the historic inn and options to move, demolish, or retain the building were investigated. Because of its connections with the American Revolution and the inn's role in the development of the community, it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. This listing required PENNDOT to assess the affects of the proposed highway improvements. After careful consideration, public meetings, and engineering studies, PENNDOT and the Federal Highway Administration determined that the best way to minimize damage was to conduct both archeological and architectural investigations of the inn, and then actually pick it up and relocate it!

While PENNDOT developed engineering plans to move the inn, found a suitable new location, and identified a new owner; researchers investigated the architectural history and archeology of the inn. The hope was that those investigations would provide some insights into the development of the property and shed some light on the daily lives of the people that lived and worked at the King of Prussia Inn.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What primary function did the King of Prussia serve over time?

2. When was the inn most historically significant? Why?

3. What are some of the legends surrounding the inn and its name? Which ones are true, false, or unknown?

4. What part does hearsay and local tradition play in the history of this inn? Much of the inn's history is not factually documented, does this make its history any less important? Why or why not? Can you think of alternative ways of discovering a site's history when not much documentation is available?

5. Why was the King of Prussia 's name changed from “inn” to “hotel?”

6. What was ironic about the role that the automobile played in the history of the inn?

7. How did listing the inn in the National Register of Historic Places help this endangered site?

8. Growth and "progress" have many times endangered historic sites around the country. Have you witnessed such a problem in your own community? If so, how was the issue resolved?

Reading 1 was adapted from Richard M. Affleck, “At the Sign of the King of Prussia,” Byways to the Past, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2002.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Archeology at the King of Prussia Inn

Archeology is the study of the past through material remains--the possessions we leave behind, or artifacts, and the marks we leave on the landscape like building foundations, trash piles or road beds, known as features. Taken together, artifacts and features make up archeological sites. By studying these items, an archeologist can learn about past or more recent cultures. To find these objects, an archeologist must dig, or excavate, in an area that humans once occupied. Then, through the type of artifacts and features found, and through historic records, archeologists reconstruct what the site's occupants were doing and when they were there. Determining the age of an artifact or feature is called dating, and there are many methods used to do this. The most simple is relative dating, which can tell us which artifacts are older than other artifacts through the law of superposition; that is artifacts closest to the surface are younger than those further down. There is also absolute dating, a technique that gives us an exact range of dates for an artifact or feature. One popular method of absolute dating is through artifacts, like specific types, shapes, and colors of pottery and glass beads, which were only made for short periods of time. Another commonly used at prehistoric archeological sites is radiocarbon, which provides a reliable estimate of age based on measurements of radioactive decay in wood charcoal, bone, and other formerly living remains found in a site. Using these methods, an archeologist can study the past and come to new and important conclusions.

Between 1991 and 2000, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation conducted several archeological investigations at the King of Prussia Inn. Through these efforts it was possible to identify a number of features and artifacts linked to different periods in the inn's history. Concentrations of refuse, the trash discarded by the property's occupants, were uncovered just to the rear of the inn and around the property. The following passages reveal what was found.

The Material Culture of the Rees and Elliot Households, ca. 1775-1860

The oldest concentration of trash on the site was found between the rear of the inn and the northbound lanes of Route 202. This remnant of the rear yard consisted of several soil layers deposited during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The two lowermost levels were datable from the 1770s through 1810, the latter part of the Rees occupation and the early years of the Elliot ownership. Many of the artifacts collected from these two levels were broken into very small pieces. This suggests that the larger portions of the broken tableware were disposed of elsewhere. What ended up behind the building were the smaller bits that were swept out the door and then trampled.

One of the more interesting aspects of the artifact collection is the relative scarcity of things common to tavern sites--tobacco pipe fragments and sherds from drinking vessels. While a few pipe fragments and a handful of mug sherds were recovered, many of the other artifacts appear to have been related to the everyday of the household activities. These items include teacups and saucers, plates, bowls, pans, and jars.

The upper levels of this area produced artifacts associated with the households of John Elliot, Sr. and his son. The few wine bottles represented can as easily be associated with a prosperous household as they can with a tavern. It is quite possible that these artifacts represent a mix of domestic and tavern-related trash.

The great majority of household goods recovered are, in fact, fragments of ceramic vessels, most of which are either teaware or tableware. Like many middling households of the early 19th century, the elder Elliots used inexpensive tableware for everyday purposes, while reserving expensive wares for special occasions. Typical of the period are the hand-painted cups and saucers and the shell-edge plates that were probably used on an everyday basis. Costlier hand-painted Chinese porcelain and English printed wares were used in more formal situations. John Elliot, Sr. appears to have replaced some of their cheaper, ceramics with more expensive blue transfer-printed forms. This increasing preference for blue tea and tablewares was maintained by John, Jr.'s family.

The excavation also provided information regarding the types of food eaten by the Elliots and their patrons. Animal bones indicate the consumption of beef stews--dishes that can be kept warm for considerable lengths of time. More expensive cuts of meat were also served, including beef loin, prime rib, mutton, and lamb. The excavations also produced a variety of items that had been discarded in the yard. Construction, repair, and maintenance of the building were attested to by glass sherds and nails. Furniture tacks and personal items were also present.

Rubbish Behind the Wagon Shed: Material from the Hoy occupation, 1871-1906

Only one archeological deposit can be linked to the Hoys, which contains nearly 900 artifacts. The datable finds indicate that trash had been deposited between 1880 and 1910. Like the earlier material, many of the artifacts related to the Hoy's occupation could have been used by both the household and the hotel patrons.

Unlike the Elliot collection, where ceramics outnumbered glass vessels, the material excavated here was more balanced. This was not a surprising result, given the advances in glass manufacturing during the late 19th century that made glass containers cheaper to produce. Manufacturers found it inexpensive to package and market their products, so consumers were presented with an array of new goods. As the cost of manufacturing dropped further, purchasers became inclined to discard them once their contents had been used. The Hoy collection reflected the range represented by glass containers, including fragments of beer bottles, a wine bottle, a pocket flask, portions of liquor bottles, and condiment bottles. Tablewares were present as well.

If the glass artifacts were typical, the same cannot be said of the ceramics recovered. The majority of the vessels were produced during the early 19th century. The reasons for this disparity are unclear. Some of these early ceramic vessels may actually be associated with the Elliot occupation. Alternatively, some of these ceramics may have been heirloom pieces. If this was the case, these pieces may have been used to enhance the “old-fashioned” atmosphere of the place. The Hoys may have been aware of the growing interest in America 's colonial past. In 1876, the Centennial Celebration of American Independence at the World's Fair in Philadelphia is said to have began a Colonial Revival Movement and a fascination with "old-fashioned" artifacts. The inn's colonial roots and its proximity to Valley Forge would have helped draw in interested visitors. If the Hoy family embraced this movement, it is ironic that they altered the hotel's 18th-century appearance with the addition of a two-story veranda which was not typical of colonial times.

Archeology of the Vernacular Colonial Revival: Anna Heist, 1920-1952

As with most archeological sites, the most recent occupation was the most visible. Over 3,000 artifacts were recovered. Three features were found, and the character of the artifact collections from each was markedly different. The upper portion of one feature contained bottle fragments and 25 whole bottles. Altogether over 100 glass vessels were identified. Ceramics included a number of tea and tablewares. Also present were nails, window glass, machine parts, metal can fragments, an eyeglass frame, doll parts, and cow bone.

The second feature consisted of several soil layers that had been deposited during the 1920s, '30s, and '40s. The 1200 artifacts recovered here were quite different from others collected. Only a relative handful of container glass fragments were found, while more than 400 ceramic fragments were recovered. The majority of the ceramics are decorated with blue transfer printing in a variety of patterns. The excavations also produced oyster shells, animal bone, personal items, horseshoes, nails, and window glass.

The third feature contained more than 1,300 artifacts, the majority of which are architectural hardware. The household artifacts recovered mainly consist of glass containers. The ceramics include sherds from five vessels; other food-related artifacts included bottle caps, a bone utensil handle, and a small number of animal remains. The rest of the collection includes machine parts, buttons, doll parts, furniture tacks, and hardware.

Much of the refuse uncovered in these features resulted from the inn's function as a place of entertainment. The liquor bottles were probably discarded after the end of Prohibition, and are likely associated with the tavern business, although some may have been used by the Heist household. In addition to serving drinks, the King of Prussia Inn also served meals. The animal remains recovered from the three features confirm the consumption of chicken, beef, pork, mutton, and oysters. These were evidently served in soups, stews, and roasts.

The presentation of food was evidently important to Anna Heist. She had assembled a collection of old-fashioned blue and white ceramics, most notably porcelain teaware from Japan. One thing the use of "old-fashioned" ceramics might tell us is that some 19th-century wares were also used as props to add to the “period” atmosphere. In an era when ceramics were being produced in new shapes and colors, blue and white pottery was “old fashioned,” which was part of its appeal to the consumer. For establishments like the King of Prussia Inn, “colonial” could mean anything two or three generations removed. It was a vernacular colonial revival that conjoined the 18th and 19th centuries into an old, but ageless, past.

Questions for Reading 2

1. What are artifacts and features? How might they help us learn about the past?

2. What was missing from the artifact collections of the Rees and Eliot occupations? Why is this noteworthy or unusual?

3. Which ceramics would the Elliots have used under normal circumstances and which for more formal occasions? How did these types change over time?

4. Which changes in buying practices did the drop in pottery during the Hoy occupation represent, and what caused these changes?

5. Why were the ceramics associated with the Hoy family unusual? Why might the Hoy's addition of a veranda to the King of Prussia be ironic?

6. What would the presence of alcoholic beverage bottles after 1929 symbolize?

7. Look up the words vernacular colonial revival. What does the term mean? Why would this tie the 18th and 19th centuries together?

Reading 2 was adapted from Richard M. Affleck, “At the Sign of the King of Prussia,” Byways to the Past, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2002.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: A New Home

In the decades since Anna Heist Waters sold the King of Prussia Inn property to the State of Pennsylvania, various individuals suggested that the building be moved in order to preserve it. Indeed, early on the Pennsylvania Highway Department had been willing to part with the structure for a nominal fee, provided the purchaser move the building to a new location. Clearly the notion of moving the inn was easier said than done. It would obviously cost a considerable sum of money, and then there was the issue of finding a new site for the inn, and providing for its renovation and long-term care. There were also doubts in the engineering community that the enormous stone structure could be moved at all without destroying it in the process. All of these concerns were eventually addressed through a partnership of federal and state agencies and a non-profit organization.Volunteers from the King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce at Valley Forge led a campaign with the historical society to assist in finding a new location and funds for the restoration of the inn. The “A Home for the Inn” campaign intended to raise the necessary funds to move the building by July 4th, 1998. The schedule proved too ambitious, but they were successful in finding a new location only a half mile east of its original location, and they committed to restoring and caring for the inn after its move. Meanwhile, the Federal Highway Administration agreed to cover 80% of the 1.6 million dollar costs for the move. PENNDOT's Engineering District 6-0 assembled a team of consultants including Greiner Inc. and Ortega Consulting to evaluate the structure and the feasibility of moving it, and the International Chimney Corporation to actually brace and move the 580 ton building.

The planning was thorough and meticulous. The route from the original location to the new one had to be cleared of utility lines and other overhead obstacles. A small culvert where a stream passes beneath Route 202 had to be braced and prepared for the weight of the massive building passing over it. A plan for conducting the move with an absolute minimum disruption of traffic had to be prepared. The inn had to be braced and bracketed with lumber and metal plates and steel cables. Enormous I-beams had to be inserted beneath the structure, and state-of-the-art, rubber tired, computer controlled, self propelled jacks had to be fitted beneath the I-beams holding the structure.

Finally, on Sunday, August 20, 2000 the King of Prussia Inn was ready for its move to a new site. A crowd gathered at dawn to watch the procession. At about 9:00 a.m., the venerable old building began to move. Traveling only feet an hour, the inn made its way up Route 202, passed safely over the culvert, to Gulph Road, where it made a right turn--with contractors soaping the tires so they could slide along the curbing and manually turning the jacks. From there the inn proceeded about a half mile to the entrance of the Abram's Run development, where it was brought to its new site. It took three days to complete this stupendous and successful effort in engineering and historic preservation!

With the successful move, the King of Prussia Inn no longer graces what was the southwestern corner of Gulph and Swedes Ford Road. But thanks to the efforts of Pennsylvania's transportation and historic preservation communities working together, the inn's history and archeology, and the inn itself, were all preserved, and an important link in the chain that binds us to our collective past was saved for future generations.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What obstacles did PENNDOT face in preserving the inn?

2. What agencies cooperated in moving the inn? Why do you think this was such an undertaking?

3. What had to be done to stabilize the structure and move the King of Prussia Inn?

4. Based on what you have learned, why do you think it might be important to preserve the King of Prussia Inn? Why do you think this particular preservation effort is so unique?

Reading 3 was adapted from Richard M. Affleck, “At the Sign of the King of Prussia,” Byways to the Past, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 2002.

Visual Evidence

Painting 1: Artist view of The King of Prussia.

(Courtesy of the King of Prussia Historical Society)

Questions for Painting 1

1. Study Painting 1. From what you learned about the inn's changing structure and architectural features in Reading 1, what time period do you think the painting is from?

2. Who lived there during this time period? If needed, refer to Reading 1.

3. What indications are there that the King of Prussia Inn was used as a business?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: King of Prussia, ca. 1910.

(Courtesy of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, Norristown, PA)

Questions for Photo 1

1. Compare and contrast Photo 1 and Painting 1. What differences do you see in the structure of the inn?

2. Photo 1 was taken in 1910. What modern inventions do you see that indicate it was taken in the 20th century?

3. Who owned the structure during this time? What purpose did it serve? If needed refer to Reading 1.

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Wagon shed during excavation.

(Courtesy PENNDOT)

Questions for Photo 2

1. Examine Photo 2. What do you think these people are doing? If needed, refer to Reading 2.

2. If you were an archeologist, what kind of questions would you ask when examining a site?

3. How might documenting the remains of the wagon shed help one understand its use at the King of Prussia Inn? If needed, refer to Reading 2.

4. Considering the fact that the King of Prussia Inn had to be moved in order to preserve the building, how important was it to conduct archeological excavations? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: King of Prussia on the move, August 21, 2000.

(Courtesy PENNDOT)

Photo 4: King of Prussia Inn finds a new home.

(Courtesy PENNDOT)

New laws and regulations put in place in the late 20th century promote careful highway planning which should result in a project that avoids a historic building completely. The best and least expensive way to preserve a historic building is to leave it in its original location; preserving not just the building, but also its historic setting.

Questions for Photos 3 and 4

1. What is happening to this building? What devices and methods relating to this action can be seen here? If needed, refer to Reading 3.

2. Compare Photos 3 and 4 with Photo 1. Do you see any structural features missing that were previously attached to the King of Prussia Inn? If so, list them. Why do you think they may have been removed?

3. Do you think that moving the inn damaged the building's integrity and historical value? Why or why not?

4. Was this the best way to preserve the building? Considering the rapid development of the area, could it have been preserved on the original site? Can you think of other ways the building could have been preserved?

Putting It All Together

In this lesson, students learn about the history of an inn in southeastern Pennsylvania and how it survived suburban sprawl. The following activities will help them apply what they have learned.

Activity 1: Community Research

Have students research a historic inn, hotel, or tavern in their community. Is this historic building still serving its original function in the community? If not, what is it being used for today? What happened to make the building's function change? Students should also research how the location of the site affected its business. Was/is it located near historically significant transportation routes? If not, is there a way to determine why it was built in that particular location? What was the site's social and economic influence on the town and vice versa? If there is not sufficient information regarding historic inns, taverns, or hotels in your community, choose a different business.

An alternate activity would be to have students do similar research on a modern local hotel. Have students interview a hotel owner/operator. Then have them compare and contrast what they learned about modern hotels to what they learned about the King of Prussia Inn. Students should give a brief oral or written report on their findings.

Activity 2: Interpreting Artifacts

Have students bring an item (preferably an antique) to class from their household (or better yet, their Grandparents household) that their peers would not immediately recognize. Each student should come prepared with information about what the item is, what it was used for, and how old it is. In class, separate the students into groups of four or five. Each student should take a turn displaying their “artifact,” while the others examine the object and use their knowledge of history to figure out what the object is, what it was used for, and how old it might be. Then the student that brought the object should reveal everything they know. Was the group able to figure out what the object was? If so, how? If not, what other information might they have needed to obtain answers? The object of this activity is to determine how difficult it is to understand an object out of context and without sources, which is what archeologist many times have to do. It also helps students realize that no matter how logical their deductions might be, many times you cannot interpret the past without more information.

Activity 3: Endangered Sites

Have students contact their local historical society or local government to find out if there is (or was) a particular historic place in their community that is (or was) endangered. What measures are being taken to save the place? How does this compare to what happened with the King of Prussia Inn? If the historic place is endangered at the present time, is there a way your class can get involved to help? Contact the person organizing the preservation efforts and design a project that will allow students to participate in the process.

If no historic places can be found locally, have students look at the National Trust for Historic Preservation website where the organization compiles a list of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. Divide students into groups having each group learn about the significance of one of the endangered places. Students should also research what efforts are being made to preserve the historic place. Hold a class discussion comparing and contrasting each group's place and each place's preservation efforts to what happened with the King of Prussia Inn.

At a Crossroads: The King of Prussia Inn--

Supplementary Resources

By studying At a Crossroads: The King of Prussia Inn students learn about the history of an inn in southeastern Pennsylvania and how it survived suburban sprawl. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce

The King of Prussia Chamber of Commerce is located in the King of Prussia Inn. Visit their website for an indepth interview with Al Paschall about moving, managing, and paying for the relocation of old buildings. Mr. Paschall led the campaign to relocate and restore the King of Prussia Inn.

http://www.kopinn.com

PENNDOT Cultural Resources Management Program

Visit the PENNDOT website for more information about their cultural resources program and for details about some of their historic preservation efforts including the King of Prussia Inn. Also included on the website are the procedures PENNDOT must follow to insure that proposed transportation improvement projects will do no unnecessary harm to the Commonwealth's heritage.

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC)

Visit the PHMC website for more information about Pennsylvania history and historic preservation. Included on the website is a section title Protecting Historic Places which provides local, regional, and federal tools to protect historic resources.

Society for American Archeology

The Society for American Archeology (SAA) is an international organization dedicated to the research, interpretation, and protection of the archeological heritage of the Americas. Included on the website is an extensive education section that provides Guidelines for the Evaluation of Archeology Education Materials among its many resources

Society for Historical Archeology

The Society for Historical Archeology (SHA) is the largest scholarly group concerned with the archeology of the modern world (A.D. 1400-present). The main focus of the society is the era since the beginning of European exploration. Included on the website are a variety of online publication links and research tools.

Valley Forge National Historical Park

Valley Forge National Historical Park commemorates more than the collective sacrifices and dedication of the Revolutionary War generation, it pays homage to the ability of everyday Americans to pull together and overcome adversity during extraordinary times. Despite the privations suffered by the army at Valley Forge, George Washington and his generals built a unified professional military organization that ultimately enabled the Continental Army to triumph over the British.

International Association of Structural Movers (IASM)

For more details and photographs about the careful moving of the King of Prussia Inn, visit the IASM magazine online.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

Search the HABS/HAER collection for detailed drawings, pictures, and documentation from their survey of the King of Prussia Inn. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.