Last updated: June 5, 2020

Article

Arts, Crafts, Clothing and Appearance

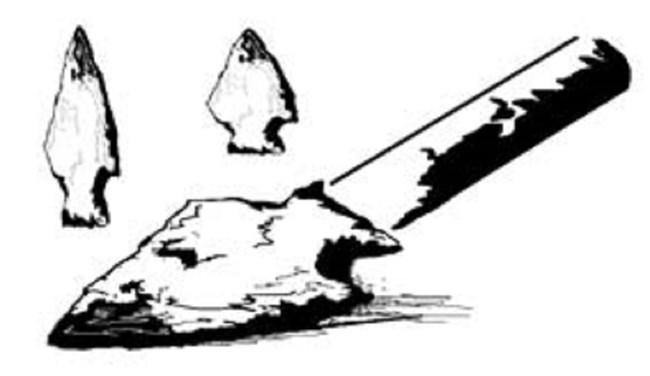

Flint

Like all American Indian groups, those people living in the villages near the confluence on the Knife and Missouri Rivers of North Dakota made tools, house wares, clothing, toys, and musical instruments from things that were available nearby or sometimes farther off if the material was important in the production of the item.Knife River flint, a dark brown, glassy quartz material, was used extensively by Knife River Indian villagers in the manufacture of chipped stone tools. The largest concentrations of the material are found in Dunn and Mercer counties of western North Dakota. A predictable chipping pattern made Knife River flint valuable as a raw material for stone tool manufacture. Gathered from pre-Ice Age deposits, flint was utilized in tool manufacture not only by the villagers but by many Native American groups for the past 11,000 years. Arrowheads are what we think of when we think of stone tools, but Native Americans made tools from flint for scraping hides and shaping wood and bone; piercing tools like awls and drills; cutting tools like knives; and chopping tools like axes. People traveled great distances to gather the raw material.

NPS

The primary flint gathering areas were located about 50 miles west of the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, in present day Dunn county. Archaeological investigation of these areas may answer questions about the life ways of the people who came here thousands of years ago.

Several different techniques were used for the shaping of tools from stone. Two basic techniques are chipping and pecking. Chipped stone tools are made from a prethinned

piece of material. Pecking was to pound one stone with another stone of equal or greater hardness. This technique was used to make grooved mauls, hammers, and war clubs.

NPS

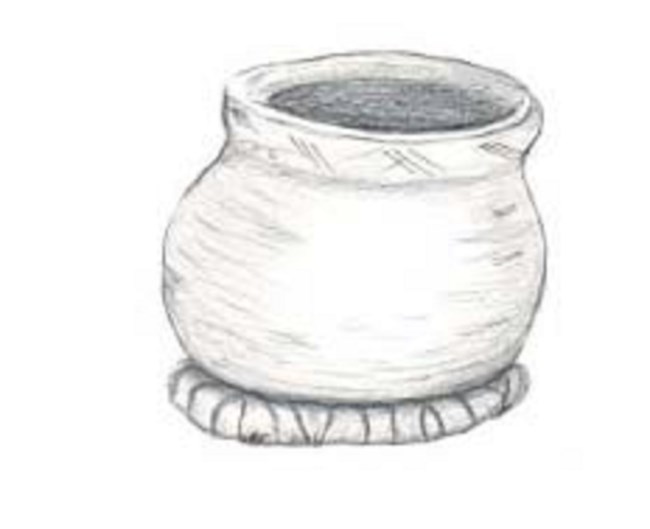

Pottery

The Hidatsa and Mandan made pottery as far back in time as their villages can be traced. This continued until the major smallpox epidemic of 1837. Pottery making was a protected right of certain women of the tribe. They made very usable and artistic pots. The pots were made by building up the sides gradually with rolled clay coils. A smooth stone or anvil was held inside the vessel with one hand while the outside was beaten using a paddle.Designs were often carved into the paddle. Designs could also be added by impressing twisted cords, pressing the fingers into the moist clay, using sharpened sticks or bones, or deeply scratching in designs. Clays used for the pottery came from deposits found along the Little Missouri river and from other deposits in the Knife River area. The clay was mixed with water, temper of sand, crushed granite, clam shells or broken bits of pottery was added to keep the pots from cracking when fired.

NPS

Painting

Painting was an important form of decoration for the Indians of this area. Pigments from the natural colors of clays were mixed with animal fat to form paint. Blood from animals and juices from plants, and trees, bark, and fruit also produced a wide range of colors. Indian women sometimes extracted the dyes from colored trade cloth by boiling it. This colored extract was then used to dye the material of their choice (i.e. quills). The traders introduced vegetable dyes, which became a valuable trade item since their use was much more convenient.Buffalo robes were painted with pictures that told a story of important events that occurred during the year. These stories recounted specific events like battles and important occurrences in the natural world. Some painting was primarily decorative such as the painting of parfleche containers.

After painting a buffalo robe or rawhide, the paint was “fixed” with glue; this glue was made by boiling hide scraping, horns or hooves from buffalo and deer. Porous bones were used as paint brushes. Capillary action draws the paint into a fine pore. When that pore is placed in contact with another material (rawhide, etc.), the paint flows out.

Most Indian items were decorated in some fashion. Their possessions were not only utilitarian, but also works of art.

NPS

Parfleche

Parfleche were containers made out of rawhide, created in a variety of sizes to hold a wide range of objects. These containers are usually folded over and whipstiched around the edges with sinew or strings made of rawhide. The containers are decorated with natural paints in contrasting colors usually with geometric, floral, animal, and other nature designs. Parfleche containers were also designed to fit over a horse so that a storage case hung on either side of the horse.Women used parfleche cases to tote their belongings on their backs. Cases were used as containers for clothing, moccasins, dried foods, sacred objects, and any other items a person might want to store or protect.

NPS

Quillwork

Porcupine quills were used for decorative work on clothing until approximately 1850 when the trade and use of glass beads replaced quills as the decoration of choice. The sewing on of glass beads was an easy adaptation to make because the same designs could be made, more colors were available, and the quills no longer had to be acquired, washed, sorted, and dyed before work could begin. While quillwork is beautiful, unique and usually very well done, there were limitations to the colors and designs which could be applied.With the introduction of glass beads of small consistent size, and great variety of color, these limitations were overcome. Most work was without a pre-drawn plan, leading to a feeling that the design belongs to each individual article. While there are many patterns which have definite meanings, the designs were frequently used simply because they were appealing to the woman doing the work. Some designs have been found that show definite European influence. Though most Plains Indian designs are geometric, the Hidatsa used some types of floral designs with no background.

Quillworking societies existed among the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara. The right to do quillwork was purchased from society members with trade goods and other materials. The society members in turn taught quillwork techniques and skills to the new members. The traditional art of quillwork continues to be taught and passed down to new artists.

NPS

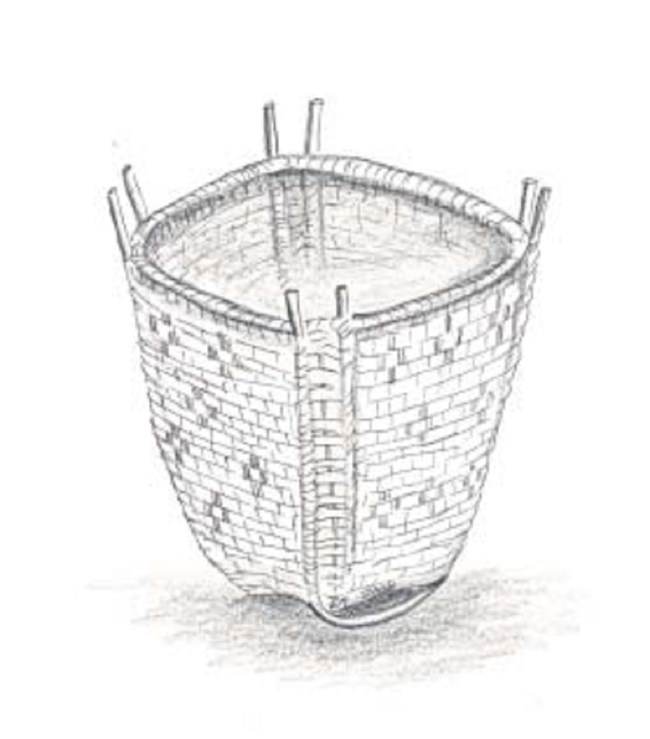

Basketry

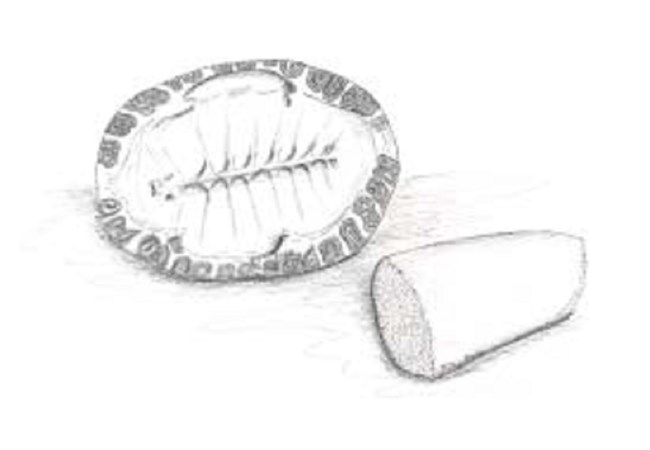

The three tribes (Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara) made baskets called “burden baskets” that were used for carrying burdens such as garden produce, berries, firewood or dirt to place on the earth lodge. These baskets were made from the inner bark of elm, ash or box elder woven onto a framework of willow sticks. After the framework and weaving materials (weavers) were prepared, a light colored weaver was wrapped around and around the uprights of the frame.The darker colored weavers were incorporated, weaving down one side across the bottom and back up the other side. This created a checkerboard effect. To make more complicated designs the darker weavers did not go over and under every light one but rather skipped in and out. The light weavers were the inner bark of the box elder which is

nearly white. The dark weavers were made by soaking bundles of prepared bark in pools of clay which had water mixed in to bring it to the right consistency. The bark would pick up the color from the clay pool after several days. These darker weavers would be rinsed and then they were ready to be woven into a basket. Small flat baskets, seven or eight inches in diameter, were also made. These were used not only for playing a dice game, but in certain ceremonies.

Clothing

The clothing of the Hidatsa and Mandan was much the same as that used by other tribes on the Upper Great Plains. The buffalo furnished much of the raw material for clothes as well as thread. The buffalo robe was the basic article of clothing. The robe was worn hair side out during the summer. It was not used to any great extent in the warmer months unless there was a formal council or other gathering of dignitaries. A particular attitude could be emphasized by varying the position and fold of a robe. For example, if a man were addressing a group, he might have his robe pulled up under the shoulders, supporting it with his left hand while he held an eagle wing fan in his right. Draping it over his entire body and head indicated anger or disapproval of some action. This was also considered a sign of shame.There were traditional patterns used to show whether the robe belonged to a man or a woman. A typical women's pattern was the "box and border" design, which consisted of a colorful border of geometric figures enclosing a highly colored and pattered box-like design on one side. A man’s robe might use a design called the “black war bonnet”, a series of concentric circles with small radiating figures made into an elongated diamond shaped design. These indicated eagle feather. This central pattern was often augmented with drawings of horses or other activities associated with the particular man, such as buffalo hunts, which were placed around the outer portions of the robe. In this way, the man was able to display his “war record” and other exploits to others.

During the first few years of life, an infant often had no clothing or costume, but might wear a part of a previously worn robe. Infants were placed in hide bags, where they spent much of their first year of life. Cattail or milkweed down was used for diaper material, and warm sand was sometimes packed around the feet for warmth in winter. At the age of one, children were expected to start walking. Small girls usually wore simple dresses, moccasins and leggings. While these items were often plain, the leggings sometimes had a horizontal strip of quillwork on the edge. The moccasins might have a small strip of beadwork or quillwork over the instep. Small boys wore shirts, moccasins, and leggings and occasionally a breechcloth.

As children grew older, their clothing adopted more defined patterns. For the girls, dresses became important. These dresses were loosefitting and had considerable variations in their decorations. Porcupine quillwork was the major type of decoration. This was replaced by beadwork as soon as traders made beads readily available. Elk teeth were also valuable items. The most highly prized elk teeth were the canines or tusks. There are only two of these canine teeth in each animal, so the incisors or front teeth were sometimes used as well. In later years, when elk were no longer available on the plains, the teeth became a very valuable trade item. Due to the high demand, people used antlers of deer and leg bones of buffalo or cattle to manufacture elk “teeth.” Some of these fake teeth were so well made that it requires careful examination to determine whether the teeth are real or not.

A typical pattern of decoration for a dress consisted of a quilled or beaded yoke over the shoulders, with elk teeth distributed over the remainder of the dress. Sometimes the entire

dress was covered with elk teeth. There were sometimes as many as 600 teeth on one woman’s dress. Leggings and moccasins were also highly decorated.

NPS

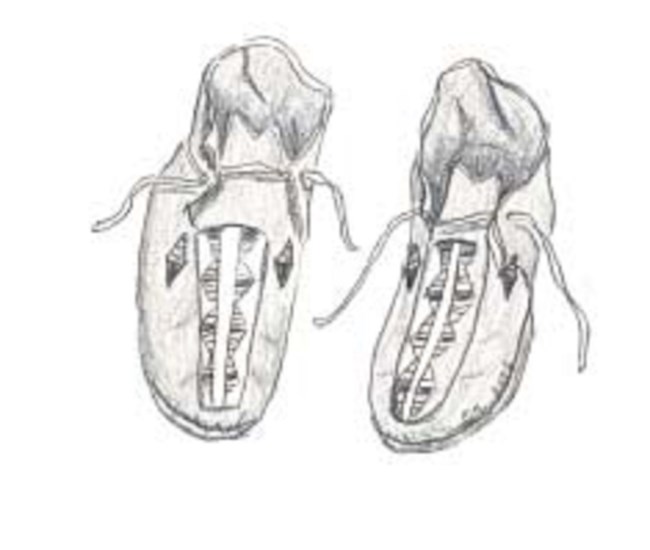

Footwear

The Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara all wore moccasins, which are considered a very comfortable form of footwear. The moccasin is still the basis for many shoe designs used today. The Hidatsa used the basic plains pattern, with a hard sole and soft upper, although they did sometimes use the soft-soled moccasin.One good source of material for moccasin soles was the top section of an old tipi cover, which had absorbed the “smoke-from-manyfires” and was virtually waterproof. The upper part of the moccasin was made from soft, tanned buckskin of elk, deer, or sometimes antelope. This upper part could be decorated using quills or beads. Awls made from sharpened bones, often ribs sections, were used to punch holes for stitches. Sinew was used for thread. Sinew is the fibrous tissue which runs next to the spine and down the legs of four footed animals. Buffalo, elk or deer sinew was commonly used by Indians. Removed at the time of butchering, it is dried and worked by beating and pounding to loosen the fibers.

When sinew thread was needed, a strand was removed from the bundle. It was customarily held in the mouth in order to soften. An inch or two at the end was usually left unmoistened in order to provide a stiff needle-like end. This fiber is strong and long lasting. Some moccasins, well over 100 years of age, are perfectly usable today. Sinew was used not only for sewing, but also to attach quillwork and beading and to strengthen the backs of bows.

In winter, moccasins were made larger than usual, in order to accommodate an inner lining made of furs or grasses, which insulated the foot. These moccasins had higher flaps. Leggings might be attached to protect the foot and ankle from deep snow.

NPS

Appearance

Indians do not have much facial hair. Hair which did appear was plucked out. A beard or mustache was not considered becoming. A pair of fresh water clam shells were pinched together to pull out the hair.Young boys and girls donned the “owl haircut.” Their hair was cut very short except for a tuft left on either side of the head above the ear, which made the children look like owls. At the age of three, the hair style was changed to a single braid hanging down the back. At the age of twelve, the girls began to part their hair and wear two braids while the boys did the same thing when sixteen.

A great deal of importance was placed on personal cleanliness. Everyone went to the river for their morning bath after being awakened by a grandfather singing war songs. In winter, water for washing was brought to the earth lodge by the women. The whole body was sometimes washed with fresh snow in the winter. They believed that this would better condition one for the cold. At other times, baths were taken in an air hole in the ice where open water could be found. On ceremonial occasions, the “sweat bath” was completed by bathing in the river—winter or summer.

Tattooing was practiced by the Hidatsa and Mandan. Women were tattooed on the lower part of the face and neck. The buffalo robe was so often worn by men with the right shoulder and arm exposed that they usually decorated only on the shoulders and right side of the body. The last known Hidatsa to be tattooed was Poor-Wolf (or Lean-Wolf), who was ninety years of age in 1909. He described the general method used for his own decoration. Several small, sharp pieces of tin were fastened to the end of a hollow bone. The piercing was done free hand, with charcoal being rubbed into the open wounds. Other accounts described drawing the design with charcoal on the skin first, then piercing.

Digital Image by: S. Fox

Singing and Dancing

Singing has always been important to the Hidatsa people as is true for the Mandan and Arikara. There are many types of songs; some for babies, women, men, societies, ceremonies, or everyone. There is always an element of sacredness to a song because you are sending your voice out into the universe. It is believed that everything is alive and just because you can no longer hear it or see it, does not mean it is not “out there.”Women have songs that they sing in their gardens to the spirit of the plants to nurture them and help them grow, just as they sing songs for their babies. Women societies have their own songs and some woman have individual songs.

Men may have songs that tell of their deeds in war which continue to be a part of oral history. Families continue to sing these songs during special occasions to honor their relatives. These songs also tie one generation to the next. Songs are made to commemorate events such as wars. Today there are songs that tell of the recent wars from World War I to Iraq. Songs are important for societies and for ceremonies and have great spiritual meaning that help to bind the people with each other and the universe.

Singing is an important art. Some men are gifted song makers and are revered for their ability to create songs including those that tell of wars and deeds of people The Hidatsa used the natural elements around them to create music. Gourds were grown and used to make rattles which are used for some songs. Buffalo hides were used to make drums. Drum making is also an important art. The drum is a sacred instrument and carries with it the heartbeat of the people. When we are in our mother’s wombs, we hear the cadence of her heartbeat. In this same manner, the sound of the drum gives us a good feeling. It can bring joy, healing, and connection to the people as we are reminded of our initial nurturing.

Dancing is another art form that has evolved over time like singing. The Hidatsa performed ceremonies of song and dance to celebrate harvest. The Mandan Buffalo Dancers danced to bring the buffalo close to the village. There were many ceremonies and occasions that had specific purposes and meaning. The songs and dances as well as dance clothes were very specific to the society and/or ceremony.

The Hidatsa purchased a dance society from a neighboring tribe in the 1700’s that still exists today. The Arikara acquired a dance society that evolved into a new dance society that also continues on. In modern times, each community has an annual celebration that includes the dance songs. Contests between the dancers on one hand and the singers and the drum on the other began in the 1960’s. The dancer had to know the songs in order to stop on time; if they didn’t know them, they could be fooled and overstep. This was very entertaining and fun. Now there are contests in many different categories as the dances evolved or were acquired from other tribes.

This evolution of the annual celebrations has become the modern day contest powwow. Contests are held in all age categories from juniors through golden age. The styles for men and boys are Grass Dance, Traditional Dance, Fancy Dance, and Chicken Dance. The styles for woman and girls are Traditional Dance, Fancy Dance, and Jingle Dress.

The dances and songs have roots in the ancient traditions of the tribes and continue through the traditional style singing and dancing; however, new styles of singing and dancing are evolving. This shows that the young people enjoy singing and/or dancing as they use their creativity to develop new contemporary styles. Singing contests are also evolving where drum groups compete against each other to see who the best singers are.

The individual songs continue to be sung and created to honor people for service in the armed forces, graduation, or serving on the pow-wow committees, or other reasons.

The pow-wow is the place where many of these honorings occur. The pow-wows bring an occasion for families to get together and renew old friendships and create new ones in a manner reminiscent of the days when the Hidatsa still lived at Knife River.

Activity in the Homes Today

Activities similar to what went on in the earth lodges continue in the home today. Women still cook, clean, sew, and raise their children. Men still visit. Women seldom decorate buffalo robes anymore. Today many women sew star quilts in their homes in preparation for donating at the pow wows in the summer or for other ceremonial or cultural events.The right to make star quilts was given to women of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara women by the Lakota women. In the days of Knife River, decorated buffalo robes would have been given as gifts. Today star quilts are designed and made to be given as gifts. Baby star quilts are often presented to newborn children as a token of love and respect. An individual who receives a star quilt made for him/her is greatly honored. Quilts are usually presented to individuals through an event often referred to as “donating.” An individual who donates may bring out large bundles of star quilts, pendleton blankets, and dry goods to the arena or circle.

A clan aunt and uncle generally receive the first donations. Traditionally, the old, the poor, the sick, and those who have lost loved ones are remembered. Civic organizations are also recipients so that they can raise funds with their donations. Women generally work all winter in the home preparing for donating. Sometimes contests are held to see who can design and make the prettiest star quilt.