From its headwaters high in Rocky Mountain National Park to its mouth in the Gulf of California, the Colorado River cuts through 1,450 miles of mountains and valleys, forest and desert. Before it was dammed, the Colorado was a mighty river, gouging canyons and swelling to a torrent when it was angry. On its lower reaches, the Colorado ran so wild in 1862 that it washed away the nascent town of Yuma, Arizona, forcing the few hundred residents to start anew. When they rebuilt, there was no turning away from the river because without it, there would be no Yuma.

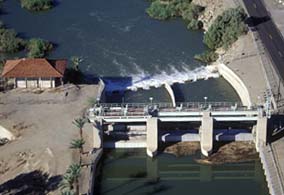

Today, with a population nearing 100,000, Yuma is an agricultural oasis made possible by irrigation works like Laguna Dam, on the Colorado River 13 miles northeast of town. At the outset, Laguna was a diversion dam, channeling water from the Colorado River to irrigate millions of acres of farmland. Wheat and cotton, lemons and tangerines, cauliflower, broccoli and lettuce turned the desert green. Yuma became famous for its lettuce--head lettuce, leaf lettuce and Romaine lettuce, a bounty celebrated every January at Yuma Lettuce Days.

Agriculture in the Yuma Valley was nothing new; the Quechan Indians used the Colorado to irrigate their fields as far back as the year 1000. But modern agriculture on the Colorado dates to 1909 and the opening of Laguna Diversion Dam, the first of many to be built on the Colorado, which, on its lower reaches, forms the border between Arizona and California. Laguna diverted river water into the Yuma Main Canal. Beginning on the California side of the river, the canal carries water southwest to fields in Imperial County, California, and the Yuma Valley in Arizona.

To enter Arizona the canal has to re-cross the Colorado River, which it does through an inverted siphon buried in the heart of downtown Yuma. The Colorado River Siphon, as it is called, is a concrete tube, 14 feet in diameter and dug 50 feet under the sandstone riverbed. The siphon acts like a tunnel; water in the Yuma Main Canal enters through an inlet on the California side, swirls 76 feet down through a vertical shaft, enters the tube, then bubbles up on the Arizona side. This curiosity can be seen by visitors who walk along the path at Yuma’s historic Quartermaster Depot, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The siphon, which delivered water to the Arizona side of the Colorado River for the first time on June 29, 1912, is just one component of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Yuma Project, authorized by Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock on May 10, 1904.

The project began with Laguna Diversion Dam, an “Indian weir” design selected after engineers studied dams in other countries where the foundations were built on sand and silt. Over the millenniums the Colorado had deposited so much silt that it seemed financially impossible to dig to bedrock. A weir is a relatively small impoundment wall that has no control structures to permit passage of water through the wall. Any excess water goes over the top. Measuring only 43 feet high with nearly two-thirds of the dam below the riverbed, Laguna resembles the Okla Weir across the Jumna River in India.

Work began on July 19, 1905, with contractor J. G. White and Company shipping materials upriver from Yuma on a steamboat or overland by wagon. Laguna is a rockfill weir, meaning it is an embankment dam with rock as the primary construction material. When rock quarried at the dam site fractured with what historian Eric A. Stene says was “an annoying regularity,” the frustrated contractor lost money, missed deadlines and turned the project over to the five-year-old U.S. Reclamation Service, which capped the top of the dam with concrete when suitable rock ran out. The Reclamation Service (today’s Bureau of Reclamation) hired mostly Mexican-American workers and gained the cooperation of the Southern Pacific Railroad, which built a rail line to the construction site.

A mile and a half below Laguna Dam, the Yuma Main Canal, constructed between 1907 and 1909, split into a second canal to serve the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation. In Yuma, the main canal split again into an East Main Canal and a West Main Canal, which ran to the Mexican border, about 20 miles distant. Yuma project canals continue to deliver irrigation water to about 68,000 acres, but today the water no longer is diverted at Laguna Dam. Imperial Dam, completed a few miles upstream from Laguna in 1938, does the job now. In 1941, diversions from Laguna Dam ended, and the outlet works were sealed permanently on June 23, 1948. Today, Laguna Dam serves to protect the toe of Imperial Dam and for partial regulation of river flows.

“Farming as we know it would not have existed without [Laguna] dam,” Tom Davis, general manager of the Yuma County Water Users Association, told the Yuma Sun in 2009, the 100th anniversary of the dam. Laguna was the first on the Colorado, and many others would follow, including Hoover Dam in 1936, Parker Dam in 1938 and Davis Dam in 1950. “The combination,” Davis said, “tamed the river.” The benefits were not without a cost, as natural riparian regions of the Colorado suffered as water was diverted elsewhere. Now efforts are underway at Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area not only to restore the region’s East and West Wetlands, but to reconnect the city of Yuma to its river heritage.

The Colorado always has been central to Yuma’s history. It was at Yuma, where the Gila River enters the Colorado, that a granite outcropping once provided a convenient place to cross the river, thus the name, “Yuma Crossing.” Indian people crossed here first, then Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. The fur trapper Ewing Young crossed at Yuma in 1826 and the American general Stephen Kearney and his army came this way in 1846 during the Mexican War. Following the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which transferred much of the American Southwest from Mexico to the United States, the U.S. Army, in 1851, established Fort Yuma on a bluff overlooking the crossing from the California side of the river. A rope ferry ran to the Arizona side, where the town of Yuma (first called Colorado City and then Arizona City) grew up as a supply depot for the fort.

In 1864, below the mouth of the Gila River, the Army built the Yuma Quartermaster Depot, which now is part of Yuma Crossing and Associated Sites National Historic Landmark. At the depot, six-month supplies for U.S. military posts in Arizona, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico and Texas arrived from California by ocean vessels. They sailed around the Baja Peninsula to Port Isabel near the mouth of the Colorado River, where cargo was loaded on streamers that plied upriver to Yuma. The Southern Pacific Railroad reached Yuma in 1877 and crossed the river on a swing span bridge, made to accommodate steamboats. By 1900, when the city counted about 1,500 residents, private efforts to irrigate the Yuma Valley began. Like so many places in the arid West, private companies faced a tough go of it. Silt accumulated in irrigation works, run-off was inconsistent, floods unpredictable and rainfall averaging only 3.5 inches a year.

When the Federal Government, with passage of the Reclamation Act of 1902, committed itself to irrigating arid and semiarid land in 16 western states and territories, Yuma County saw an opportunity. Potential water users formed the Yuma County Water Users’ Association to contract with Reclamation for the Yuma Project. Reclamation purchased the local irrigation and ditch companies and moved into units of the old Quartermaster’s Depot, abandoned in 1883 after the coming of the railroad. A contract for Laguna Dam was let on July 6, 1905, opening the way for the Yuma region to have a stable, year-round supply of water.

Adding to Laguna Dam’s unusual “Indian weir” design are nine-inch swastikas embedded in its masonry piers. These, the Yuma Sunwrites, stem from the trip engineers took to India, where they “came across a symbol that represented a Hindu goddess with power over water. They thought it would be appropriate to place the symbol on the Laguna Dam.” It wasn’t until years later that the swastika became controversial as a symbol of Nazi Germany.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017