Beginning around 300 B.C., the Hohokam practiced irrigated agriculture in the Salt River Valley of Arizona. Hohokam farmers dug hundreds of miles of canals, some as much as 30 feet wide and 10 feet deep – a remarkable accomplishment achieved with only hand tools and human labor in this land of extremes. The Salt River can be bone-dry one month and a flooding torrent the next, when the winter rains come or the snowmelt rushes down from the White Mountains, where the Salt originates. Named for its brackish waters, the Salt River rises in eastern Arizona and flows southwesterly for more than 200 miles before converging with the Gila River just west of Phoenix.

The Hohokam built their complex irrigation system, said to rival those in ancient Egypt and China, on both sides of the Salt, leading to the growth of stable urban centers populated by as many as 50,000 people in the basin alone – and this in the midst of Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, where temperatures can reach 120 degrees. Then, sometime around 1,400 A.D., the Hohokam abandoned the settlements they had called home for at least 1,700 years. When the Spanish arrived less than a century later, they found Indian peoples living along the Salt on lands previously occupied by the Hohokam, still farming using canal irrigation. Today, the Pima (Akimel O’odham) and Papago (Tohono O’odham) believe the Hohokam—a Pima word meaning “those who have gone”—to be their ancestors.

Some archeologists link the ancient Hohokam’s departure to environmental circumstances such as droughts or repeated flooding. Or perhaps the intensive irrigation created waterlogged soil. Waterlogging deprives plants of the oxygen needed to grow, and can also build up amounts of salts in the soil sufficient to kill crops.

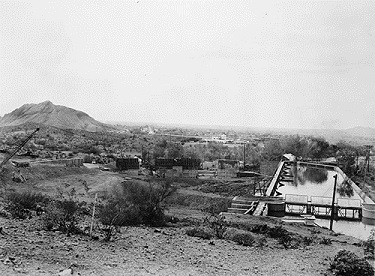

By the late 19th century, centuries after the Hohokam departed, settlers from the United States and Mexico arrived with dreams of establishing farms and towns along the Salt River. In 1903, the U.S. Reclamation Service began the massive Salt River Project, which once again brought consistent water to the basin’s cultivators. But this new influx of water was so great that over several years it raised the water table, perhaps recreating—nearly 500 years later—the same conditions that led to the Hohokam’s departure. However, Reclamation found a solution: pumps powered by hydroelectricity could draw water out of the drenched land. Reclamation had constructed its Crosscut Powerplant – with more plants to come – on a canal at the center of the Salt River Project, with the ambition to sell the power to local farmers and industries to offset project costs, but it soon also fueled these efforts to drain the soil.

Before Reclamation came to the Salt River Valley, the settlers who established Phoenix and other towns in the late 19th century followed in the Hohokam’s footsteps. By then, only traces of the Hohokam canals remained. The settlers dug new canals—including the Arizona, the Grand, and the original Crosscut—the latter of which, as the name suggests, cut across to connect the Arizona and Grand. Although they built irrigation canals, they could not afford to build a storage reservoir, so each year farmers and ranchers watched as the river surged with the spring snowmelt, with no way to store the excess water for summer use. Motivated by their frustration, they joined with other westerners to lobby for a Federal program to build large irrigation projects. These efforts led President Theodore Roosevelt to sign the Reclamation Act of 1902. In 1903 the new U.S. Reclamation Service was given approval to build the Salt River Project.

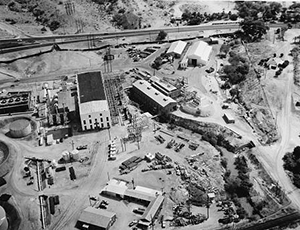

The farmers in the Phoenix basin who wished to be part of the Salt River Project formed the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association and, in 1903, the Association partnered with the Reclamation Service to harness the Salt River’s run-off. They built Roosevelt Dam to store irrigation water, and an irrigation system created largely by expanding the existing canals that Reclamation had purchased from the non-Federal owners. In 1910, with the Salt River Project well underway, the Association proposed a plan to supplement the power generated at the Roosevelt Powerplant, which supplied energy to Phoenix, a city increasingly embracing the electrical age. By constructing more powerplants, the Association knew it could sell the excess power and use the revenue to repay the project’s high construction costs. Under contract with Reclamation, the Association dug a “new” Crosscut Canal between the Arizona and Grand canals, by then owned by Reclamation, with the intent of building a powerplant on the new canal.

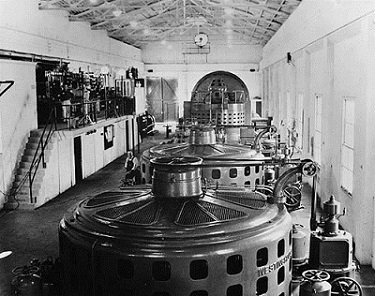

The new Crosscut Canal was built 3 ½ miles east of the “old” Crosscut Canal (which remained in use for drainage purposes) for two principle reasons: 1) the steeper slope in the location of the new Crosscut Canal would create more “head”, utilizing a 112-foot drop for hydroelectric generation; and 2) the location of the new canal and powerplant would be near two existing electric distribution lines. By 1915, the new Crosscut Canal and Crosscut Powerplant were completed. The Neo-Classical-style, rectangular, gable-roofed, concrete powerplant is divided into 12 bays on its north and south sides, and three bays on its east and west sides, with streamlined classical features including a corbelled band course and pilasters. Here, Reclamation installed six custom Pelton water wheels that handled the canal’s variable volume and silt-laden water. The plant expelled the water into the Grand Canal, which began at the Crosscut Powerplant outlet. The powerplant’s construction on a canal enabled power production simply by taking advantage of water that was already flowing to local farmers for irrigation use.

The new powerplant, forebay, pipes, and transformer house, all constructed of reinforced concrete, stood at the epicenter of the vast Salt River Project power and canal system. As the only low-head powerplant on the project when it began operation, the Crosscut plant supplied nearly 40 percent of the Salt River Project’s generating capacity with its 3,000 kilowatt capacity. (“Low-head” generally refers to hydropower that utilizes naturally flowing river currents or tidal flows, rather than the pressurized releases of water from reservoirs. In the case of Crosscut, which had only a 112-foot drop compared to the nearly 250-foot fall at Roosevelt Powerplant, the source of the hydropower was the irrigation water flowing within the Crosscut Canal, upon which the powerplant is located.)

Three years after the plant’s completion, trouble surfaced when a Reclamation survey found that ground water in the Salt River Project area was puddled below the topsoil. Almost 40 percent of the irrigated acreage was in danger of waterlogging. In response, Reclamation increased the number of drainage and irrigation pumps by almost 1,000 percent, from nine in 1918 to 87 in 1923, decreasing the threatened land from 67,000 acres to only 17,000. Thus did hydroelectric power find a new purpose on a Reclamation project—powering pumps to drain the land so settlers could remain on their wrung-out farms.

Power generation became such a priority on the Salt River Project that, when extensive droughts hit in the 1920s and 1930s, Reclamation and the Water Users’ Association decided to build a back-up powerplant that did not rely on water. In 1939, they built a diesel-and-steam-powered plant next to the Crosscut hydroelectric plant, which supplied the first non-hydroelectric source of power to Salt River Project customers and provided security to both power users and farmers. Today, the Crosscut hydroelectric powerplant is on “water order” only, meaning water only runs through the plant when water users order their water shares, and the plant only runs if the water shares released are large enough to operate the unit. When there are insufficient water orders, the penstock gates remain closed, and water simply bypasses the powerplant and flows directly from the Crosscut Canal into the Grand Canal.

During World War II, an industry boom in Phoenix transformed the valley, and change continued as increasingly mobile Americans ventured west. People arrived in droves, whether to start a business in the promising metropolis or to comfortably enjoy the “Valley of the Sun” from their air-conditioned vacation homes. Many farmers sold their fields to developers as land values rose and farming expenses increased.

Today, canals still crisscross the landscape, their adjacent trails and parks drawing joggers and bicyclists while the centuries-old history often goes unnoticed. Reclamation’s Salt River Project, built upon the ancient Hohokam and early pioneer irrigation networks, brought water and hydroelectricity to the valley and contributed to Phoenix’s rise as one of the America’s largest cities. The Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association now operates along with the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District under the name of Salt River Project (SRP), an entity that provides electricity to two million people and delivers close to one million acre feet of water per year to central Arizona farmers.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 3, 2018