Bartlett Dam, on the Verde River northeast of Phoenix, was the first multiple arch dam built by the Bureau of Reclamation. The distinction stems from the timing of Bartlett’s birth in the midst of the Great Depression. As bids were let in the fall of 1935, cost was a prime concern. Bartlett’s buttresses were hollow and its arches thin, meaning less material was needed, saving on concrete and freighting costs. The sophisticated design also required more laborers to shape its nine buttresses, 10 arches, and a short gravity section at each end of the dam--a boon in years of high unemployment. When completed in May 1939, Bartlett Dam was 286.5 feet tall and 800 feet long, and the highest multiple arch dam in the world.

Bartlett Dam, named for a government surveyor, is a relatively late component of the Bureau of Reclamation’s complex Salt River Project, which led to the development of central Arizona and includes not only dams and reservoirs, but hundreds of miles of canals. Without the project, historian Robert Autobee writes, “Phoenix would still be the domain of the cactus and snake instead of the corona of the ‘Valley of the Sun.’”

Bartlett Dam, the first on the Verde River, is one of six storage dams comprising the Salt River Project, which involves both the Salt and Verde rivers in central Arizona. Two of the dams were constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation (Bartlett and Theodore Roosevelt), three by the Salt River Valley Users Association (Horse Mesa, Mormon Flat, and Stewart Mountain), and one (Horseshoe) by the copper mining company Phelps-Dodge under a water exchange agreement with the Salt River Valley Users Association.

So extensive is the system of dams on the Salt River east of Phoenix that they form a chain of lakes 60 miles long. The largest lake--and once the largest manmade lake in the world--is Theodore Roosevelt Lake, which covers more than 17,000 acres when full. The reservoir stores water behind Theodore Roosevelt Dam, completed in 1911 as the Bureau of Reclamation’s first multipurpose dam, providing not only irrigation and flood control, but hydroelectric power to Phoenix.

Other dams followed in the 1920s and, in August 1936, work began on Bartlett. The purpose of the dam was to tap the Verde River for the many private users in the Salt River Valley, as well as for the Salt River Indian Reservation, home of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. The Verde River, named for the malachite deposits along its banks, was considered one of the most unpredictable rivers in Arizona. The river lived up to its reputation during construction of Bartlett Dam as record-breaking floods interrupted work twice.

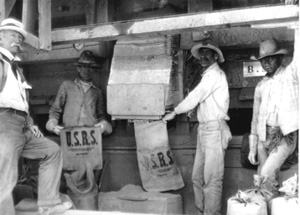

The long and complicated battle between competing groups to tap Verde water dates to 1889, but it wasn’t until July 1936 that the California contractor, Barrett, Hilp and Macco Corp., arrived in the desert to begin Bartlett Dam. The contractor built roads and a work camp--dormitories and houses for 200 laborers, a dining hall, commissary and recreation halls, a school, and a hospital. The Bureau of Reclamation built a warehouse, a shop, and living quarters for its engineers, as well as installing its own phone system to Phoenix.

As workmen prepared the canyon walls, excavated the spillway, and dug to bedrock, construction engineer E. C. Koppen pored over drawings and wrestled with ways to make the complicated design “readily understood by a gang of carpenters.” The design was innovative; it had not one arch but 10, although Arch No. 9 and Arch No. 10 were partial arches due to the steepness of the canyon abutment. Nine buttresses, spaced 60 feet apart and left hollow to save material, provided support, as did a short gravity section at each end of the dam. On February 7, 1937, just two days after the first concrete was poured, the Verde River crested at its greatest flow on record, 62,500 cubic feet per second, as compared to its normal flow of under 500 cfs. (A cubic foot equals 7.48 gallons.) More flooding on February 15 and March 17 partially destroyed the temporary coffer dams built to turn the Verde aside during construction. Contractors brought in nine pumps to dry out the construction site, but that wasn’t enough, so deep well turbines were used. By year’s end, Bartlett was only 38 percent complete. Then another massive flood poured down the Verde in March 1938, peaking at 108,000 cfs. By then, however, all but Arch No. 2 were above the stream bed, so damage was minimal.

In addition to flooding, a contract requirement that concrete could not be poured when the temperature exceeded 95 degrees threatened to sabotage the dam’s 1,000-day construction deadline. To speed up the process, the Bureau of Reclamation, with the contractor’s help, designed a “fog spray” to artificially cool the freshly poured concrete. A low-heat concrete was also used. When Bartlett was completed in May 1939, it not only had met its deadline, but was also under budget by $270,000. Thankfully, the contractors had purchased flood insurance.

Events leading to construction of Bartlett Dam date to the early 1900s, when the Salt River Project was among the first five projects authorized by the U.S. Reclamation Service, created by the Reclamation Act of 1902. The next year, the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association, representing 4,800 individuals in the Phoenix area, pledged their lands as collateral to receive Federal funding for a reclamation project on the Salt River. In 1911, Theodore Roosevelt Dam was completed on the Salt, 76 miles northeast of Phoenix. In 1917, the Water Users’ Association took over operation and maintenance of the Salt River Project, which included a diversion dam, two main canals, and hundreds of miles of secondary canals. Backed by private funding, other dams followed throughout the 1920s.

Finding ways to irrigate the desert had been at the center of Arizona’s history for centuries. Two thousand years before Americans settled in central Arizona’s Salt River Valley, the native Hohokam people developed an extensive canal system to water a harsh land where less than an inch of rain might fall in June and temperatures could soar to 120 degrees. Then again, as happened in February 1890, the Salt River could rise 17 feet in 15 hours, overflowing its banks, and washing away crops and adobe homes. In February 1891, the Salt spread nearly three miles wide and demolished the railroad bridge between Tempe and Phoenix, leaving Phoenix without a rail connection for three months. In January and February of 1905 the Salt River raged again, wiping out a 100-foot section of the privately owned Arizona Dam, a timber-crib structure that diverted water into the Northside Canal system, making irrigation difficult.

Americans had been slow to settle in the Salt River Valley, arriving some 20 years after the end of the Mexican War and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which transferred California and much of the American Southwest, including most of Arizona, to the United States. In 1865, Fort McDowell, a government outpost on the Verde River, seven miles from its junction with the Salt, provided a market for settlers. One settler was Jack Swilling, a former Confederate soldier who made good use of an irrigation ditch long abandoned by the Hohokam. With $10,000, Swilling and 12 other men dredged the “community ditch,” which supplied water to grow hay for government horses, sparking the settlement that became Phoenix. In 1870, the valley had a population of only 235, but with water development came more people. Boasting a growing season of 305 days a year, settlers planted fruit trees, alfalfa, and grain. In 1887, a railroad spur reached Phoenix, allowing for the marketing of crops, and by 1900 Maricopa County recorded a population of 20,457.

With growth came new canals until a total of 15 crisscrossed the valley by 1912. The region’s early history was marked by battles over water rights and failed efforts to unite neighbors to build a storage dam so that water could flow when needed. Things were no less contentious when irrigators focused attention on the Verde River, which forms southwest of Flagstaff and meanders 195 miles southeast before emptying into the Salt River just east of Scottsdale. The Verde flows through the reservation of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, as it nears its confluence with the Salt River.

Attempts to tap the Verde dated to 1889, but competing groups tangled for more than 40 years over who needed the water, how much was available, who owned what rights, who had the financial means to build a dam, and who should manage the project once built. Finally, in 1927 and 1928 a cooperative agreement was worked out, only to be rejected a year later. Then the stock market crashed, ruining the bond market. With private investment no longer an option, Federal funding became the only way to finance a dam on the Verde River. Soon, as historian David M. Introcaso writes, the project was touted as a work relief project and a way to fulfill the government’s obligation to provide water to 6,310 acres on the Salt River Indian reservation. After a long and litigious battle, which included a promised loan that was rescinded from the New Deal’s Public Works Administration, the Salt Valley Water Users’ Association, with political might on its side, entered into an agreement with the Federal Government to build the dam on the Verde. The Association was assigned 80 percent of the price tag, while the Federal Government, on behalf of the Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, paid 20 percent.

Bartlett Dam and its reservoir, Bartlett Lake, played a role in the unprecedented growth of Phoenix when World War II brought war industries and war work to the city. Today, Bartlett Lake, with a capacity of nearly 180,000 acre feet of water, is the second largest in the Phoenix area and offers boating, camping, and picnicking (An acre foot is 325,851 gallons, or enough water to cover an acre one-foot deep.) Bartlett Dam was modified between 1994 and 1996 to address safety concerns. Among the changes was raising the dam 21.5 feet to prevent overtopping.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017