Last updated: August 15, 2019

Article

Architectural History at Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Architectural History at Golden Gate National Recreation Area, 1860s to 1950s

U. S. Army Architecture

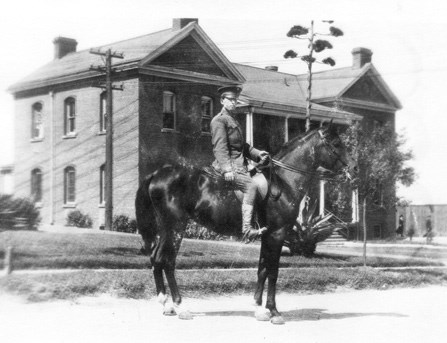

The majority of Golden Gate’s historic buildings were constructed by the United States Army from as early as the 1860s. The army established their first military post here at the Presidio in 1847 and with the advent of the Civil War, they established posts at Fort Mason, Fort Point and Alcatraz. The army’s job was to defend the city from enemy attack, so their first construction priority was to immediately build powerful seacoast defense batteries and cannon. However, the military buildings at Golden Gate consist of much more than just batteries and bunkers. Hundreds of soldiers were assigned to operate the new coastal defenses and posts were established to provide housing and life’s necessities for these hard-working men. Over the next one hundred years, the army would build all types of buildings including barracks, mess halls, officers’ quarters, gymnasiums, stables, bakeries, hospitals, and airplane hangars. As a result, the park contains a terrific collection of military buildings that represent a wide range of architectural styles, starting with the Greek Revival style continuing up through the Vietnam and Cold War era.

Most of the army’s key construction periods are associated with military activity; the army usually built new buildings or established new posts when they were ramping up and preparing for war. The Greek Revival buildings are associated with the Civil War; the Colonial Revival buildings are associated with the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Endicott Period (1895-1910). The Mission Revival buildings were built at the end of World War I and the park’s “temporary” wood-frame 1940s-type barracks were built to support the army’s tremendous activity here during World War II.

Standardized Military Building Plans

As early as the Civil War, the army used standardized building plans to facilitate the rapid construction of any new army post. The Office of the Quartermasters General, located in Washington, D.C, would dispatch standard building patterns to the proposed site. The standard plans functioned as a complete construction kit for each type of building and included floor plans, elevations, section details and construction instructions.

When the army was establishing a new post, anywhere in the country, they would send for Quartermaster standard plans to help build the new buildings. This explains why you can still find the same type of buildings at many different historic bases across the nation.

The Army’s Version of Architectural Styles

The primary goal of the Office of Quartermasters General’s was to provide the most basic buildings for the soldiers, while they were defending the country. As a result, the Quartermaster building designs were not particularly trendy or current. The army building patterns consisted of simplified versions of popular East Coast architectural styles, but frequently, the selected styles were ten to fifteen years out-of-date. The army’s version of the civilian styles was often more restrained and limited, in keeping with the minimal needs of a military base. The only exception was to the commanding officer’s residence, where the Quartermaster’s office would assign more architectural details, like finer moldings or an elegant entrance, his buildings to help remind everyone of his high military rank. Smaller, utilitarian buildings such as warehouses and garages would be designed very simply.

Even with the use of standard building plans, the army buildings were not always constructed as originally designed. At the individual posts, the availability of certain building materials and often local weather conditions could result in deviations from the standard prescribed buildings. Once the plans were received at the post, if the funds or building materials were not readily available, the structures were often erected quickly with limited supervision or guidance, and with whatever materials were on hand. For example, the large Colonial Revival buildings at Fort Baker were originally specified for brick, but when the construction bid came back three times higher than anticipated, the army construction manager decided to build to buildings in wood-frame instead. Differences in regional weather patterns also required the army to modify the imported building plans, especially in the porch details. Because the Quartermaster General’s office was in the East Coast, with hot and humid summers, most of the standard building plans were designed with open porches, that provided a cool, outdoor living space. Once these buildings were constructed in San Francisco, however, the prevailing fog during San Francisco’s summers was often so strong that spending anytime on the front porch was unpleasant. Over time, the army began to enclose many of the porches with glazing to provide the much-needed wind break.

For Further Readings:

- What Style Is It? A Guide to American Architecture: John C. Poppiliers and S. Allen Chambers, Jr. John Wiley and Sons, New Jersey, 2003.

- Identifying American Architecture: A Pictorial Guide to Styles and Terms, 1600-1945: John J.-G. Blumenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1981.

- A Field Guide to American Houses: Virginia and Lee McAllester. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 2002.

- National Park Service journals, tech notes and preservation briefs: www.nps.gov/history/publications.htm

- “Parkitecture” in Western National Parks: www.nps.gov/history/hdp/exhibits/parkitect/