Last updated: November 25, 2024

Article

The Archeology of Rocky Mountain National Park’s Young Reformers

National Park Service sites needed workers for large-scale undertakings and could enact federal programs quickly, and so they welcomed CCC enrollees. Six camps and at least two supplementary “stub camps” sprung up in or just outside of Rocky Mountain National Park under the purview of the Fort Logan district in the Eighth Corps area. Though the Department of Labor facilitated the recruitment of enrollees, and Park Service staff dictated the projects at specific sites, the War Department, specifically the US Army, administered the day-to-day aspects of enrollee life. As a result, the CCC generally ran like a military operation.

But these young men were not military trainees. For a six-month enlistment period, they eradicated nonnative plant species, made wooden directional signs, and installed telephone lines, among other efforts to attract visitors to the park’s wilderness. This all fell to the wayside with the onset of World War II and the termination of the CCC initiative. For years, incomplete summaries and final reports curbed the idea of telling Corps stories.

Archeological excavations of the Civilian Conversation Corps camps at Rocky Mountain National Park are similarly unfinished, but in consideration with historical records, they uncover enrollees’ daily lives and movements. In detailing what enrollees did as much as what they undid, archeology reunites their small traces with the network of stories to which they belong.

Big Successes Despite Scant Remains

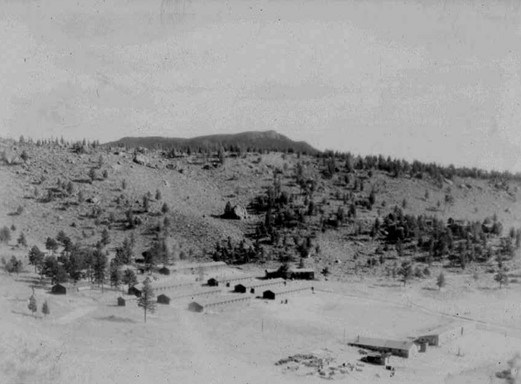

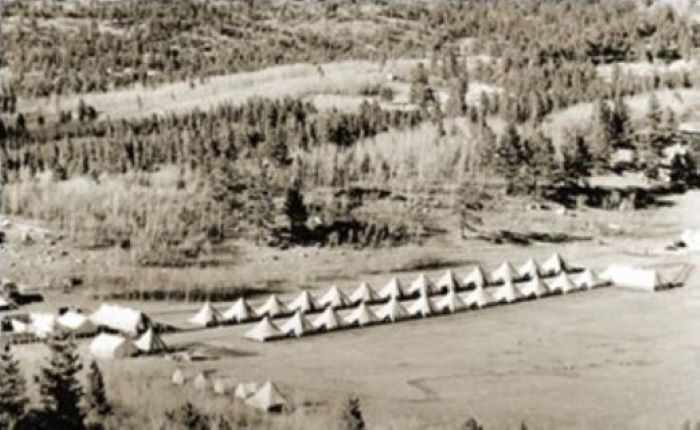

The first of Rocky Mountain’s CCC camps, NP-1-C operated in Little Horseshoe Park in the summers from 1933 to 1938. Accommodations included 24 tents for quarters, 4 larger hospital tents, and a field kitchen, all neatly flanking the two sides of a single street. In 1999, a field crew from the University of Northern Colorado mapped the 35-acre site using GIS technology. Among the remains they found were privy depressions, gravel platforms, cellar depressions, and two large terraces cut into the hill sides that provided flat surfaces for tents. Scattered pieces of bottle and window glass, leather, and utensils were likely used, broken, and discarded by CCC camp occupants. Memos, letters, and reports from 1941 to 1942 disagree on which of the camp’s buildings were later transferred to the NPS, but they concur they were razed to restore the natural landscape.

Operating in the summer of 1933 and 1934 on Beaver Creek at Phantom Valley was camp NP-3-C. NP-7-C re-occupied the area from the summer through the winter of 1935 and again for the summer of 1938. NP-7-C was replaced in 1940 by NP-12-C, which was established near Grand Lake and ran until 1943. Thomas Lincoln of the Midwest Archeological Center first archeologically recorded NP-3-C in 1978, though he mistook it for Squeaky Bob Wheeler’s Hotel de Hardscrabble about a half a mile north. His observations, however, align closely with Robert H. Brunswig, Jr.’s archeological maps from the 2000 recording of the site. For instance, he noted several rock lines/walls that seem to coincide with pathways to tents seen in photographs from a CCC alumnus.

At the NP-3-C site, a University of Northern Colorado survey crew in 2000 observed a low linear mound of rock and dirt about 20 feet long and 20-feet long depression at right angles. Both may represent foundation walls, likely for a more permanent cooking/eating facility. The survey also yielded shoes, Prince Albert tobacco cans, buttons, and rock cairns. Also notable are pencil inscriptions by CCC camp members on the upright wood timbers of the Triumph Mine, a site located in the Kawuneeche Valley to the north of the NP-3-C camp. CCC camp members’ notations render names, such as “Harry E. Buchman, Honey Grove, TX” and “Norwin,” and lighthearted messages like “Write me any time please.”

Little else likely remains from the CCC camps at Rocky Mountain because they participated in their own destruction. According to former Park Ranger Bert McLaren, the CCC removed many old cabins, associated trash, abandoned mining equipment, and camp structures before they vacated the park. When they were gone, park personnel continued to break down evidence as it suited their changing needs.

Original maps of camp layouts are absent for all camps but NP-4-C. The photographic record is spotty, and photographs that do exist rarely depict vehicles or individuals, so it is difficult to imagine the camps bustling with hundreds of young men. Even so, the CCC’s contributions cannot be so easily erased. A six-page single-spaced memorandum enumerates the accomplishments of the CCC camps at Rocky Mountain National Park. Enrollees’ deeds included constructing two bridges and 33 new buildings, landscaping more than 42 acres, planting 2,565 trees and shrubs, and even devoting 339 man-days to fire fighting.

To understand Rocky Mountain National Park as it appears today, one must appreciate the breadth of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ involvement. And to understand the Civilian Conservation Corps’ involvement, one must understand the importance of the archeological record at the park, for although it is scarce, it enroots enrollees in the sprawling landscape they revitalized.

Brock, Julia. Creating Consumers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Rocky Mountain National Park. M.A. Thesis, Department of History, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 2005.

Butler, William B. “The Archeology of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Rocky Mountain National Park.” National Park Service, 2006.

Paige, John C. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History. National Park Service, 1985.

Rocky Mountain: Administrative History 1915-1965. National Park Service, 1971, Chapter 7: The Depression and the CCC.

To understand Rocky Mountain National Park as it appears today, one must appreciate the breadth of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ involvement. And to understand the Civilian Conservation Corps’ involvement, one must understand the importance of the archeological record at the park, for although it is scarce, it enroots enrollees in the sprawling landscape they revitalized.

Resources

Brock, Julia. A History of the CCC in Rocky Mountain National Park. Report to Rocky Mountain National Park, National Park Service, 2005.Brock, Julia. Creating Consumers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Rocky Mountain National Park. M.A. Thesis, Department of History, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 2005.

Butler, William B. “The Archeology of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Rocky Mountain National Park.” National Park Service, 2006.

Paige, John C. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History. National Park Service, 1985.

Rocky Mountain: Administrative History 1915-1965. National Park Service, 1971, Chapter 7: The Depression and the CCC.