Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

The Archeology of Chinese Railroad Workers at Golden Spike National Historic Site

On May 10, 1869, during an elaborate ceremony at Promontory Summit in Utah, the “Golden Spike” was driven in and the nation’s first Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Newspapers of the time highlighted the corporate “race to Promontory” and technological advancement, and many acknowledged the significant contribution Chinese laborers made to the project. However, these were all second-hand accounts. The voices of the approximately 11,000 Chinese workers who labored on the Railroad faded or were left out entirely. Their day-to-day experiences help tell the full story of how this incredible engineering feat was accomplished.

Archeology, the scientific study of past humans, is one way those experiences can be recovered. The artifacts and features the Chinese laborers left behind have helped scholars understand much more about their daily lives working on the railroad. While the rails themselves were torn up in 1942 for WWII scrap iron, the Golden Spike National Historic Site preserves evidence directly connected to railroad construction, temporary workers’ camps, and the remains of the town of Promontory. This evidence includes changes made to the landscape such as grades, cut rock faces, fills, drill marks, trestles, culverts (drainage tunnels), and remnants of the telegraph system. These features help archeologists understand how workers used and moved throughout the landscape and testify to the immense amount of time and labor required to build the Transcontinental Railroad.

Archeology, the scientific study of past humans, is one way those experiences can be recovered. The artifacts and features the Chinese laborers left behind have helped scholars understand much more about their daily lives working on the railroad. While the rails themselves were torn up in 1942 for WWII scrap iron, the Golden Spike National Historic Site preserves evidence directly connected to railroad construction, temporary workers’ camps, and the remains of the town of Promontory. This evidence includes changes made to the landscape such as grades, cut rock faces, fills, drill marks, trestles, culverts (drainage tunnels), and remnants of the telegraph system. These features help archeologists understand how workers used and moved throughout the landscape and testify to the immense amount of time and labor required to build the Transcontinental Railroad.

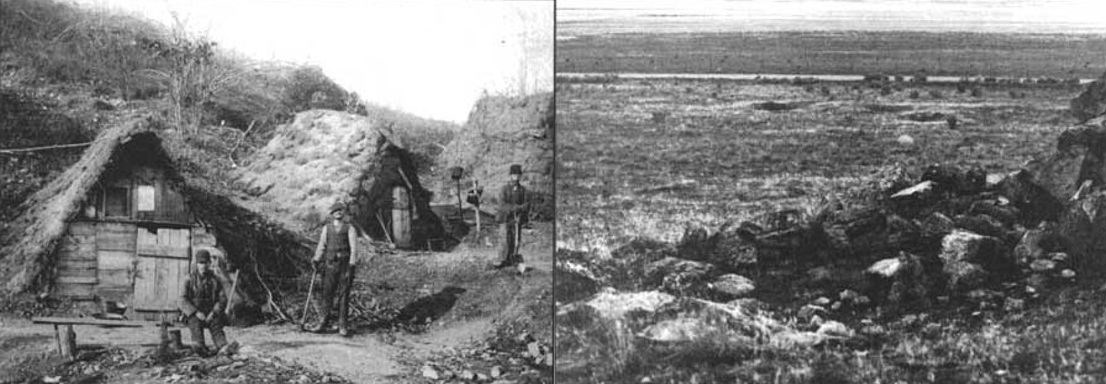

Homstad et al., Figs. 39 and 41

Archeologists have also analyzed more permanent settlements along the railroad including the town of Promontory. The town was originally formed as a workers’ tent camp in 1869 while the final section of the railroad was completed. After the final spike was driven in on May 10, the town functioned as a support station, complete with telegraph and ticket offices, businesses, and saloons. A variety of people occupied the town until its abandonment in 1942, including Chinese individuals who worked as railroad laborers, cooks, or small business owners.

Raymond and Fike, Fig. 69

When taken together, the archeological materials discussed above help uncover Chinese individuals’ experiences both during construction of the Transcontinental Railroad and directly afterwards. It is through archeology that these narratives can be restored to their rightful place within the historic record.

Resources

Homstad, Carla, Janene Caywood, and Peggy Nelson. Cultural Landscape Report: Golden Spike National Historic Site: Box Elder County, Utah. Cultural Resources Selections No. 16. Intermountain Region, National Park Service. 2000.Merritt, Christopher W., Michael R. Polk, Kenneth P. Cannon, Michael Sheehan, Glenn Stelter, and Ray Kelsey. Rolling to the 150th: Sesquicentennial of the Transcontinental Railroad. In Utah Historical Quarterly 85 (4): 352-363.

National Park Service. Golden Spike National Historic Site: Box Elder County, Utah. Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Travel Itinerary.

National Park Service. Golden Spike National Historic Site.

Raymond, Anan S. and Richard E. Fike. Rails East to Promontory: The Utah Stations. Cultural Resource Series, No. 8. Bureau of Land Management. 1994.

Tags

- golden spike national historical park

- archeology

- archaeology

- asian american and pacific islander heritage

- aapi

- asian american and pacific islander history

- golden spike

- golden spike national historic site

- railroad

- railroad history

- intermountain region

- campsite

- town

- 19th century

- railroad workers

- excavation

- utah

- asian american

- chinese