Last updated: July 31, 2024

Article

The Archeology of Chinese Laborers Who Connected the Country

Primary sources detailing their day-to-day experiences in their own voices are scarce. No personal writings, letters, or diaries authored by Chinese workers on the first transcontinental railroad have been found. Eyewitness accounts and visual images come from just a handful of primary sources—all by European American and European observers—and often reflect anti-Chinese sentiment of the time. Through archeological analyses of the artifacts and features these workers left behind, and through the stories passed down through generations of their descendants, the legacy of their tenacity outlives the physical tracks themselves.

A Dream Slowly Becomes a Reality

Congress provided funding for the Army to survey five potential transcontinental railroad routes between 1853 and 1855. The Railway Act of 1862 authorized the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and later the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) to build the western and eastern portions, respectively, of the chosen route.Initial progress was slow. Labor shortages, often fueled by strikes and an unwillingness to increase wages, compelled Superintendent J.H, Strobridge, at the urging of his friend Charles Crocker, to fill the CPRR’s vacancies with Chinese immigrants. Strobridge reluctantly agreed to hire 50 men, then 50 more, until some 11,000 Chinese individuals were employed in the construction of the Pacific Railroad by 1868.

Chinese laborers, recruited first from California and then directly from southern China, held a range of positions, from graders and tracklayers to masons, blacksmith helpers, and cooks, but were paid an average of 30% less than their European or European-American counterparts. With few exceptions, the CPRR did not record names of individual Chinese workers, at least in surviving historical records. Instead, they were organized into groups of up to 30 men, each of which had a leader responsible for receiving and distributing their wages.

The race to complete a railroad line to Utah Territory brought a competitive spirit along with dangerous working conditions. CPRR crews faced both sub-freezing and sweltering temperatures, blizzards and avalanches, bad water, blasting accidents, and innumerable other hardships. These dangers resulted in the loss of an unknown number of worker’s lives, though the total probably reached the hundreds or even the thousands.

Averaging nearly three-miles of construction per day, Chinese-led CPRR crews entered Utah Territory in March, 1869, and by April and May of 1869, railroad construction camps covered the slopes of Promontory Summit, the junction where the two companies would meet. On April 28, 1869, in just 12 hours of work, Chinese construction crews and a smaller group of non-Chinese workers helped lay 10 miles and 56 feet of track, a record which has not been surpassed. Before noon on May 10, eight Chinese men moved the final rail into position, followed by a host of guests that drove the ceremonial golden and silver spikes. Yet Chinese faces are absent from photographs that showcase the crowd’s celebrations.

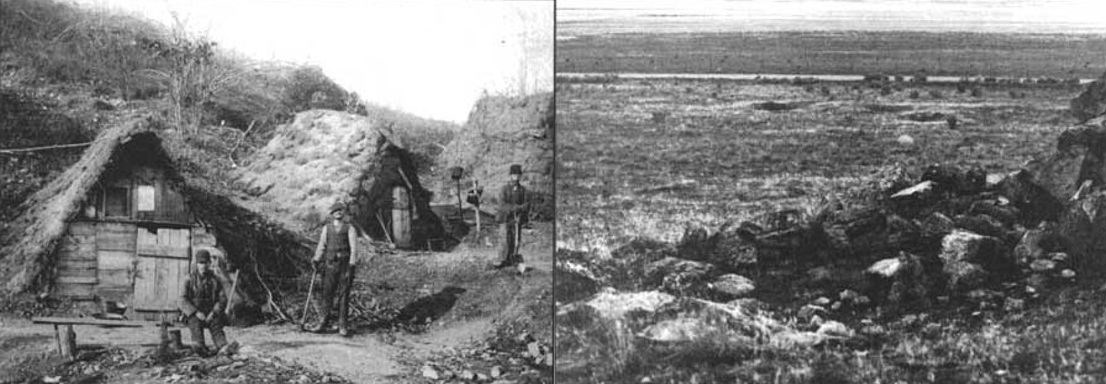

Homstad et al., Figs. 39 and 41

Addressing an Archeological Paradox

Researchers face a paradox: artifacts and structures are anchored in specific places, but the Chinese laborers who deposited them are represented through materials strewn across thousands of miles.Archeological remains of about 31 worker campsites and supply camps have been found on the slopes of Promontory Summit, and hundreds have been located throughout the North American West. These remains are the only evidence of the frenzy of human activity that characterized the last months of construction and the completion of the railroad line.

Archeologists excavated Chinese dwellings in several locations along the railroad. A range of tents, dugouts, and formal houses demonstrate both the initial construction and much longer period when crews were maintaining the railroads. A defining feature of these short-term work camps is the shelters needed to protect workers from the elements. Today, shallow depressions survive as traces of this housing, called dugouts.

A Collective Contribution

Despite inequal treatment, many Chinese workers stayed in the railroad industry after the completion of the transcontinental railroad. The construction of later transcontinental, branch, and regional railroads heavily depended on the expertise of Chinese veterans of the CPRR, providing steady employment at a time when Chinese immigrants were shut out of most industries. Few of these Chinese individuals became wealthy themselves, but their savings were the foundations for personal and community-wide growth, as in Terrace, West Lake, and East Lake. Even so, after the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, many railroad jobs trickled into other immigrant communities, with most Chinese workers replaced on our nation’s railroads by 1910.The CPRR’s practice of omitting Chinese workers’ names makes it difficult to recognize individual contributions. A few identified Chinese railroad workers, taken from the Southern Pacific Bulletin, are Ah Hop, Toy Gee, and Charlie Dan. Some of them dedicated nearly 50 years of labor to the CPRR. However, for immigrants like Lee Wong Sang, who passed through CPRR work camps in California, Nevada, and Utah between 1866 and 1869, railroad construction work was only a short segment of their lives.

Even though the present often excluded them, all Chinese railroad workers risked their lives through hopes of achieving a better future. For many, this future did not materialize. For many more, their fates are unknown. Archeology replaces the label of “Silent Spikes” for Chinese railroad workers with the rightful commemoration of their specific successes in uplifting their communities and linking an entire country.

Resources

Chinese Labor and the Iron Road. National Park Service.Homstad, Carla, Janene Caywood, and Peggy Nelson. Cultural Landscape Report: Golden Spike National Historic Site: Box Elder County, Utah. Cultural Resources Selections No. 16. Intermountain Region, National Park Service. 2000.

Merritt, Christopher W., Michael R. Polk, Kenneth P. Cannon, Michael Sheehan, Glenn Stelter, and Ray Kelsey. Rolling to the 150th: Sesquicentennial of the Transcontinental Railroad. In Utah Historical Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 352-363.

Nakayama, Don K. Chinese Railroad Workers, the Transcontinental Railroad, and the Indispensability of Immigration to America. The American Surgeon, vol. 90, issue 2.

Raymond, Anan S. and Richard E. Fike. Rails East to Promontory: The Utah Stations. Cultural Resource Series, No. 8. Bureau of Land Management. 1994.

Voss, Barbara L., et al. The Archaeology of Precarious Lives: Chinese Railroad Workers in Nineteenth-Century North America. Current Anthropology, vol. 59, no. 3, 2018, pp. 287–313.