Part of a series of articles titled Yellowstone Science - Volume 26 Issue 1: Archeology in Yellowstone.

Next: Archeology Facts

Article

When Yellowstone National Park (YNP) was created in 1872, much of the western Great Plains and Rocky Mountains remained uncharted wilderness still dominated by various Native American tribal groups, some of which were fighting for their own survival. Though the southern Plains Indian wars were winding down, Custer’s defeat on the Little Bighorn was still four years away. Nonetheless, YNP quickly caught the imagination of the American public with accounts of steaming geysers, bubbling hot springs, and other geological wonders. By the mid-1870s, a few settlements had sprung up in surrounding mining regions; and although there were virtually no roads and mostly Indian trails to follow on horseback, a few adventurous citizens visited YNP on sightseeing and other excursions. The creation of YNP and its earliest “use” exemplifies the European American concept of a “park” as a place that must remain in a natural state. It was into this setting that the Nez Perce (Nimi’ipuu or Nee-Me-Poo) entered in the summer of 1877, and when they learned from white captives that they were in a National Park the idea of preserving such a small area must have been difficult for them to comprehend given their dependency on the natural world for their basic needs and survival. Such collisions of culture and philosophy continue to shape the West and its people even today.

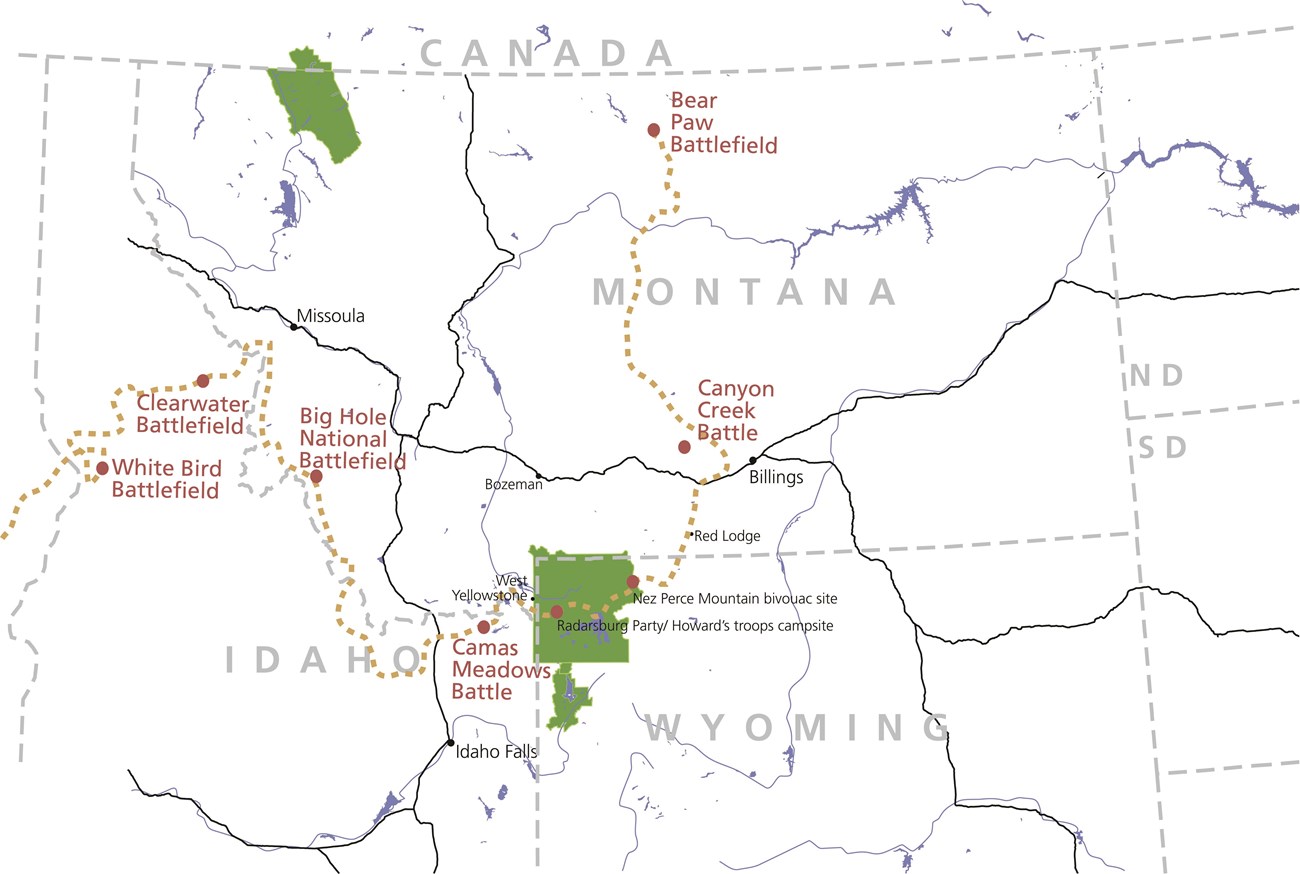

To commemorate the flight of the Nez Perce, Congress inducted the 1,170 mile-long Nez Perce Trail (NPNHT) into the National Trails system on October 6, 1986, through an amendment to the National Trails System Act of 1968 (figure 1). About 84 miles of the NPNHT is within YNP. Beginning in 2006, the National Park Service undertook a multi-year archeological inventory project along the Nez Perce trail through the park. These efforts not only identified locations of several Nez Perce, U.S. Army, and tourist encampments, but also clarified the general route the Nez Perce followed through the area.

The 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce

Summer 1877 brought inescapable change for the Nez Perce. The 1855 treaty of Walla Walla, ratified by Congress in 1859, established a seven million acre Nez Perce reservation on traditional lands in parts of what would become the states of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. The discovery of gold in 1860 resulted in an uncontrolled influx of miners and settlers onto reservation lands, and in 1863 the U.S. Government elected to renegotiate the treaty and shrink the reservation to approximately one-tenth its original size. This resulted in a schism within the Nez Perce leadership between those willing to sign the new treaty (treaty Nez Perce) and those who were not (non-treaty Nez Perce). Many of the treaty bands had been Christianized and stood to benefit from the new arrangement; whereas non-treaty bands, who were known for crossing the Bitterroots to hunt buffalo, often with the Crow, and retained much of their traditional culture, were unwilling to relinquish their traditional homeland. The new treaty was ratified by Congress in 1867. By 1877 Indian-white relations in the area had deteriorated to such a degree that an ultimatum was issued by the government that all non-treaty Nez Perce must relocate within the new reservation by June 14. On June 17 U.S. army and volunteer soldiers approached a Nez Perce camp on Whitebird Creek in western Idaho. When a party of six warriors bearing a flag of truce approached the soldiers, one of the volunteers fired at them, thus precipitating the Nez Perce War of 1877.

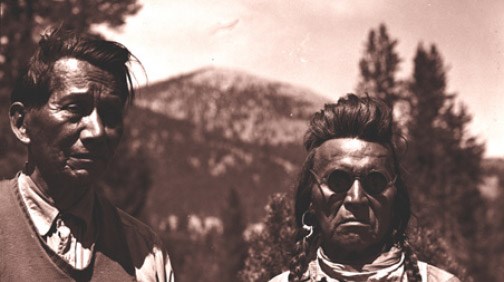

After the outbreak of hostilities, a group of roughly 250 warriors and 500 elders, women, and children, with over 2,000 horses embarked on what would become a 1,170 mile long trek that ended on October 5, 1877, at the Bear Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana, approximately 40 miles south of the Canadian border (figure 1). During this time the Nez Perce were led by chiefs Ollokot, White Bird, Toohoolhoolzote, Looking Glass, and Hinmst-owyalahtq’it (Joseph) (figure 2). General O.O. Howard, Commander, Department of the Columbia, pursued the Nez Perce throughout their flight, although their final defeat was to forces led by Colonel Nelson A. Miles, Commander, Tongue River Cantonment, Department of Dakota. After their surrender, about 200-300 Nez Perce managed to avoid Miles’ pickets and cross into Canada while the remaining survivors were sent to Indian Territory in present day Oklahoma. Today, descendants of non-treaty bands live among three groups: the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, and the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho.

The Nez Perce travelled through a wide array of environmental conditions and habitats: wetlands, riparian areas, open meadows, mountains, and plains. The journey included four battles and several skirmishes with the U.S. Army. Even though there were no major military engagements within YNP, several incidents did occur between the Nez Perce and civilian tourist groups and ranchers, as well as Bannock scouts employed by the army.

On August 23, 1877 the Nez Perce entered YNP via the Madison River near present-day West Yellowstone. The main contingent followed the Madison and Firehole rivers to Lower Geyser Basin then crossed the Central Plateau and Hayden Valley, forded the Yellowstone River, continued around the north shore of Yellowstone Lake and traversed the rugged terrain through the Absaroka Mountain Range, probably exiting the park sometime between September 4-6. Their route likely followed pre-existing trails for much of the way. Howard’s army followed essentially the same route as the Nez Perce and often occupied their same campsites until the Yellowstone River, at which point they turned north in an attempt to intercept the Nez Perce somewhere on Clark’s Fork on the east side of the Absaroka mountains. Once reaching Barronett’s Bridge, the army followed the road to the Cooke City mines through the Lamar Valley and then crossed the divide to the upper Clark’s Fork. During this time, however, Nez Perce raiding and scouting parties were active and headed north into Mammoth Hot Springs, Stephens Creek, Lamar Valley, and the Clark’s Fork. Twenty-two tourists also came into contact with the Nez Perce within the park. All were robbed, several were shot, two were killed and a number captured, including some who were used as guides.

Focus on Collaborative & Interdisciplinary Research

YNP consulted with descendants of the non-treaty groups who participated in the 1877 war. They shared oral histories of the ordeal and information on traditional knowledge and use of the Yellowstone region unavailable through other sources, such as areas their ancestors may have been selected as campsites. As archeologists, we use this information not only to assist in locating sites related to the 1877 events, but also to incorporate concerns of Nez Perce through proactive management and stewardship of these important places.

Nez Perce elders reported that prior to 1877, their people used the area that is now YNP to hunt, trap, fish, trade, and visit with other tribal groups, such as the Crow and Shoshone. Their leaders used routes that they had learned from their elders. They knew park terrain and deployed advanced scouting parties as well as rear guard to avoid capture by the army. They would read the land to determine where important resources were, and camp near water and grass for their horses (Sucec 2006). In such situations only wikiups, a lodge consisting of a frame covered with matting or brush, would have been constructed and used by traveling Nez Perce (figure 3). They also stated that trees were stripped of their edible cambium if the group was short of food. Elders confirmed that several scarred trees near the Yellowstone River reflect cambium harvesting. Hydrothermal areas were used for their curative powers and to give an extra edge for success in their activities.

Working with the park archivist and park historian, NPS staff reviewed all potential sources of information and compiled relevant historical documents, maps, first- and second-hand army, civilian, and Nez Perce accounts; newspaper articles; soldiers’ journals; photographs; and written collections. The information provided a rich historical background and context for events in YNP. These Nez Perce oral histories and historical accounts were analyzed to identify likely candidate locations for the 1877 events within the 84 miles of the trail within Yellowstone.

These data were valuable aids during archeological fieldwork and in several instances helped tie historical events to specific locations in the modern landscape. Archeological survey was conducted between 2006 and 2015 by the Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist Survey Section, National Park Service archeologists and student interns, the University of Calgary, and members of the Nez Perce Tribe and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Once designated search areas were identified, we looked for objects dating to an 1877 temporal context that could have been used by military, civilian, and/or Nez Perce. These included such items as horse tack, clothing items (military insignia, buttons, buckles, suspenders, etc.), mess equipment (forks, knives, spoons, etc.), and food remains (tin cans, etc.). Prehistoric sites composed of chipped stone and ground-stone tools were also recorded. Given the relatively late occurrence of the Nez Perce War, a vast array of metal objects had been incorporated into Nez Perce material culture, and an assortment of similar items would have been used by the U.S. Army and civilian participants as well. Park research permits allowed us to collect diagnostic artifacts for further analysis and conservation. Blaze marks, axe-cut stumps, hearth remnants, and other modifications to the local environment were also recorded.

Connecting the Past to the Modern Landscape

Although the team was able to identify several Nez Perce, U.S. Army, and tourist encampments, space requirements limit the discussion to the following sites associated with the 1877 events to provide us a glimpse into the material culture of the time.

Radersburg Party Camp & Wagon Abandonment Site

Camped along Tangled Creek in the Lower Geyser Basin, the Radersburg Party (from Radersburg, Montana) consisted of George and Emma Cowan; Emma’s brother and sister, Frank and Ida Carpenter; acquaintances, Charles Mann, Andrew Arnold, William Dingee, Albert Oldham, and Henry Meyers. The party used the area as a base camp for a couple of weeks from which they split into smaller groups to explore the geyser basins and the falls on the Yellowstone River. On the day before their capture, the party returned to this camp in preparation to leave. Nez Perce scouts sighted their campfire that night, but decided to wait until morning before approaching it.

At first light on August 24, 1877 a small party of Nez Perce led by Hímiin Maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf) approached the camp. After the initial encounter, Nez Perce numbers quickly multiplied; and the Radersburg party decided to pack the wagons, saddle the horses, and head north as quickly as possible. When they departed camp they did so under the escort of 40-50 warriors. One of the Radersburg tourists described the Nez Perce procession as three miles long and driving 1,000 to 1,500 horses up the trail. Near the mouth of what is today Nez Perce Creek, the party was informed that they could not continue and forced to accompany the main Nez Perce group up-valley. Above Morning Mist Springs, the Radersburg party had to abandon their two wagons and the majority of their equipage due to thick timber. Horses from the wagon teams were saddled and a few articles of clothing were taken by the hostages before their captors confiscated their goods and made the wagons unusable.

The group then traveled up-valley to a large meadow complex at the base of Mary Mountain. After a short council, tribal leaders released the group and the party, now on foot, began their return trip to the Firehole River. After about a mile a group of warriors approached and recaptured them, although several of the tourists were able to escape at this time. After marching back to the council area, a melee ensued, and George Cowan and Albert Oldham were shot and left for dead. Emma Cowan and Andrew and Ida Carpenter were taken hostage but were released the following day when the Nez Perce crossed the Yellowstone River at Nez Perce Ford.

Howard’s advance scouting party found Cowan and Oldham in the Lower Geyser Basin several days later and camped in the area from the afternoon of August 30 to the morning of August 31. This camp was later named Camp Cowan, as it is where George Cowan was rescued and given aid after his ordeal. Stanton Fisher, Chief of Scouts under General Howard, noted, “The Indians had cut up the harness, cut the spokes out of the buggy, and scattered things around promiscuously” (Fisher 1896). In the years that followed, surviving members of the Radersburg Party revisited these locations on several occasions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Few artifacts were identified at the Cowan Party camp on Tangled Creek. The opposite holds true for Camp Cowan, which had high artifact densities representing later occupation which may be the result of it being used by many different parties over time, as well as a large Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the 1930s. However, a cluster of temporally diagnostic historic artifacts located near Morning Mist Springs is consistent with the location where the Radersburg party was forced to abandon their wagons. Three roller buckles, a harness terret, and a snap hook could represent remains of the wagon harness observed by Fisher in 1877. Similarly, George and Emma Cowan’s accounts by sketches and a journal indicate the party had writing implements, perhaps pens with extra nibs, and the nib found could have been one of these. A full length, brass Parker Brother’s shotshell was recovered that possessed attributes indicating that it was made between 1874 and 1877. Cowan and Oldham later filed depredation claims against the U.S. Government and the Nez Perce tribe for losses they incurred during these events. A number of items recovered from this site may relate to specific items and property types listed in Cowan’s claim. Items range from a breech loading shotgun to horse tack and breechings and other items specifically listed in their claims such as blankets and clothing, as well as unspecified items probably grouped under “provisions” likely confiscated by the Nez Perce. These actions reflect the severe lack of material goods that the Nez Perce were suffering due to the conditions of open warfare, with no source of resupply.

The Nez Perce Mountain Bivouac Site

Another success of this project was identification of perhaps the only known intact Nez Perce campsite within the park related to the 1877 war. Located near the headwaters of the Lamar River 25 miles into the back country at an elevation of nearly 10,000 ft., this site probably represents the last bivouac of the main group of Nez Perce within YNP. P.W. Norris’s 1880 account of an Indian camp is the earliest written record describing this site:

“Just above … were still standing the poles of one Indian lodge, while there were more than forty others that had fallen, but which evidently had been used the previous year; many still older also remain … this Indian perch commands a fair view of all approaches. Abundant pasturage for game and domestic animals was had in the notches of the numerous adjacent canyons … Fragments of china-ware [sic], blankets, bed clothing, and costly male and female wearing apparel here found, were mute but mournful witnesses of border raids and massacres” (Norris 1880).

The site was first investigated in 1961 by Aubrey Haines, Ken Feyhl, and Stuart Conner, who found numerous flaked stone tools and debitage, historical artifacts, and evidence of bark stripping and axe-cuts on a number of trees, interpreted as possibly resulting from harvesting pitch wood for kindling. Period artifacts recovered include an assortment of metal objects as well as brass, iron, and wood components of a pre-1874-pattern McClellan saddle, culturally modified trees, and preserved lodge poles.

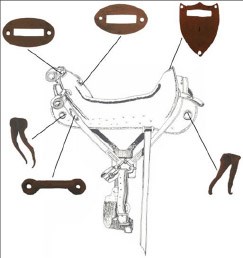

Artifacts collected from the site were found in two distinct areas (A and B) that lie about 380 ft. (115m) apart. Selected artifacts in Area A include a tinkler and tinkler preform, an Indian-made iron projectile point, iron ring and foot staples, brass pommel shield and brass cantle guard plates to a pre-1874 Pattern McClellan saddle, a possible canteen spout fragment, a probable handle from a Pattern 1874 U.S. Army tin cup, a handle from a probable Pattern 1874 meat can, a .44-40 Winchester Center Fire (WCF) cartridge case, a brass grommet possibly from a U.S. Army rubberized pancho, a brass bar-buckle, several Ausable, type horseshoe nails, and at least two Richardson and Robbins solder-patch and side seam cans (figure 4). Tinklers (also known as bangles, danglers, v-cones, and tinkling cones) were cone-shaped pieces of rolled metal attached to clothing edges as decorations and sound producers. Both the tinkler and tinkler preform possessed remnants of tinning on their surface that allowed speculation they were manufactured on-site from food cans. All of the military-related items are basically of a post-Civil War or early 1870s temporal context. The Richardson and Robbins brand of the 1870s was considered by some as “luxury goods” (in this case the can was for plum pudding) and their advertising specifically targeted “excursionists and travelers for their luncheons” (Smith 1976, Heite and Heite 1989, Heite 1990).

Additional McClellan saddle parts were found in Area B in 2013. Efforts to recover the saddle were undertaken in 2015, requiring materials necessary to safely stabilize and transport the saddle remnants back for conservation and study. A total of 29 saddle parts were recovered from a 1x2-m excavation unit. Portions recovered include most of the iron reinforcing and fastener hardware from a pre-1874 Pattern McClellan saddle along with numerous pieces of wooden saddle tree and several remnants of leather strapping (figures 5 & 6). In addition, three .44-40 WCF cartridge cases were found a few meters from the saddle parts.

The McClellan saddle parts found in areas A and B are viewed as pieces of the same saddle that was likely manufactured around either a Pattern 1858 or 1864 saddle tree. The saddle hardware is consistent with a pre-1874 McClellan saddle pattern that was in common use during the Indian War period of the 1870s. No evidence was found that would provide an explanation for the presence of the saddle or the fact that it was broken apart prior to abandonment. The disarticulated condition and distribution of the saddle parts indicate the saddle was broken into pieces prior to abandonment. Neither the brass pommel shield or cantle guard plates were found in association with the other saddle parts, indicating these pieces were taken from the saddle prior to abandonment. The McClellan saddle was not considered a highly desirable prize by Native Americans, probably due to the fact that many tribes designed and manufactured their own saddles. In many cases when an army saddle was captured by Indians, it was stripped of its leather covering, hardware, and stirrups after which it would sometimes be salvaged; but in many cases it was merely abandoned.

Several .44-40 WCF cartridge cases were also found in areas A and B. The .44-40 WCF was chambered for the model 1873 Winchester and was introduced that same year. By 1877, the Model 1873 Winchester had become a popular weapon among various tribes of the Plains and Rocky Mountains. Considering .44-40 WCF cartridge cases were at the Big Hole and Bear Paw battlefields, it is safe to assume this particular type of weapon and ammunition were in possession of the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War.

Culturally modified trees are trees possessing physical alterations that reflect human utilization of forested ecosystems, and many were observed within the forests near the site. These include both axe-cut (pole size) stumps and a number that had been stripped of large sheets of bark, probably for cambium recovery. Approximately 110 standing axe-cut stumps were observed in timbered areas around the site. Typically 30-42 inches tall and 3-6 inches in diameter, these stumps only become obvious after close inspection due to their similarity to other deadwood accumulations. Many axe-cut stumps still retain bark, while some have totally shed the bark layer. It is believed that the axe-cut stumps represent the harvest points for poles composing the standing and collapsed lodges mentioned by P.W. Norris in 1880. Dendrochronological analysis of a sample (n=6) of axe cut stumps revealed that three died prior to 1877 while three died during the late growing season of 1877 (see sidebar, page 35). The specimens dating prior to 1877 could have been harvested as standing dead, while harvest of the other three would have occurred in late August or September, the same time as the Nez Perce would have occupied the site. The axe-cut stump dates are considered some of the strongest evidence for interpretation of this site as a bivouac occupied by the Nez Perce during the 1877 war. The presence of 1870s-period military and non-military artifacts at the site further corroborates the tree-ring analysis, indicating the site likely functioned as a Nez Perce bivouac during the 1877 Flight.

Remains of the 40 lodges described in the 1880 Norris account may also be present at the site. These took the form of clusters of highly weathered pole-sized pieces of wood up to 1 m in length located in hollows situated well away from the present tree line. Modern NPS accounts indicate that unauthorized out-of-bounds campers may have been using pole remnants for firewood during the last 50 years. If so, unauthorized firewood collecting impacted our knowledge of the site with a devastating loss of information, potentially including lodge locations and their distribution which could have provided information on residential patterns during the flight.

The few camp descriptions provided by survivor accounts suggest the Nez Perce often stopped for lunch; that fires were kindled for breakfast, lunch, and supper; and that shelters were constructed nightly. Emma Cowan’s observations from the night of August 24, while being held captive in the Hayden Valley, provide important insights, “The Indians were without tepees which had been abandoned in their flight from the Big Hole fight but pieces of canvas were stretched over a pole or bush” (Guie and McWhorter 1935). Cowan’s account implies that in the absence of their usual equipage, the Nez Perce had adopted expedient practices relating to not only fast travel, but also a basic need for shelter amounting to little more than a stretched rope or a few joined poles over which a covering was placed. This account implies that rather than transporting lodge poles, the Nez Perce harvested them nightly (probably close to camp) and abandoned them when camp moved.

Four cambium-harvested trees, typically larger than 12 inches in diameter, are also present at the site. One of these was sampled for dendrochronologic analysis which indicated the cambium was peeled during the early growing season of 1826. Preserved axe or other tool marks show the outline of the bark sheets removed during the peeling process when the trees were still alive. Cambium peeling involves removal of usually semi-circular sheets of bark from living trees for different purposes. Cambium harvest and consumption was a relatively common practice among native people of the Columbia Plateau as well as groups inhabiting other areas of the Rocky Mountains. Historic and ethnographic accounts indicate cambium harvest and consumption was a normal part of the annual cycle of some native people, especially during the spring months. Lewis and Clark report bark peeling and consumption of sap and the soft part of the wood among the Northern Shoshone: “[T]he natives had pealed [sic] the bark off the pine trees about this same season. This the indian [sic] woman (Sakakawea) with us informs that they do to obtain the sap and soft part of the wood and bark for food” (Thwaites 1904). Nez Perce elders have also reported the practice in times when the group was short of food.

Although none of the artifacts found during the investigations at the mountain bivouac site can be associated with any particular Native American group, it remains highly likely that these items were brought to the site by the Nez Perce and abandoned upon their departure. Similarly the McClellan saddle parts probably originated as property stolen from the army, as such instances were common during the Indian War period. The association of these items with cans and other goods would also be consistent with property the Nez Perce obtained through raiding of both civilian and military sources. Some Nez Perce may have possessed canned and other goods procured by scouting and raiding parties actively foraging for needed items. Some items, however, such as chinaware, “costly male and female wearing apparel,” and Richardson and Robbins plum pudding, might have been relatively rare in the region at the time. One potential source for such items is listed as “A quantity of provisions and clothing belonging to claimant and his wife,” of the value of $350.00 on lines 12 and 15 of the depredation claim filed in 1892 by George Cowan (Radersburg tourist party) for property losses incurred on August 24, 1877.

The mountain bivouac site could have been occupied by the main group of Nez Perce or a splinter group, or it could have been a rendezvous point for multiple groups after taking different routes through YNP. Archival information indicates the Nez Perce camped in this area sometime between September 4 and 6, 1877. Considering the number of people and horses that would have comprised the main group, it is quite possible (especially if they occupied the area for several days) that the Nez Perce were spread over a fairly large area to assure ready access to water, wood, and grass, with the current site area representing only a fraction of the area actually occupied. When P.W. Norris first rode through the camp in 1880, there was evidently an intriguing pattern of standing and collapsed lodges with a noticeable amount of debris of European American origin that he attributed to raids by Indian groups. The association of the stolen goods and perishable material with the standing and collapsed lodges undoubtedly conveyed a feeling of tragedy to the situation. Today the site lies in wilderness that has changed little since the Nez Perce camped there in 1877.

Moving Forward

Archeological research enabled the identification of a segment of the route taken by the Nez Perce as they crossed the Absaroka Mountains to continue on their journey northward. Working with the Nez Perce National Historic Trail managers in 2017, the NPS formerly incorporated this segment of their journey into the pedestrian Commemorative Trail Route so visitors can honor the experience of the Nez Perce. The park looks forward to continuing to tell the story of the 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce, including the multiple routes used by the various U.S. Army units; Nez Perce scouting parties led by Hímiin Maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf) and Kosooyen and other Nez Perce splinter groups; and the civilian Radersburg and Helena parties, as well as other civilian encounters in the park.

There are many cultural resources along the trail, and it is up to us to preserve and protect the trail and its sites for those who come after us. Archeological sites are non-renewable, in that once disturbed they cannot be replaced or repaired and when damaged, important information is lost forever. Natural and historic sites should be left undisturbed for all who visit, as it is an important part of our heritage.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Yellowstone Park Foundation (now Yellowstone Forever), National Park Service, and U.S. Forest Service for supporting this project. We also wish to thank the Office of Wyoming State Archaeologist, University of Wyoming, and tribal elders from the Nez Perce Tribe and Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation who were able to collaborate in the field on this project, and the Confederated Tribe of the Umatilla Reservation who consulted on this project.

Literature Cited

Brown, M.H. 1967. The flight of the Nez Perce. Putnam Press, New York, New York, USA.

Cleland, C.E., editor. 1971. The Lasanen Site: an historic burial locality in Mackinac County, Michigan. Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA.

Crabtree, D.E. 1968. Archaeological evidence of acculturation along the Oregon Trail. Tebiwa 2. Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho, USA.

Dorsey, R.S, and K. L. McPheeters. 1999. The American military saddle, 1776-1945. Collectors’ Library, Eugene, Oregon, USA.

Eakin, D.H.2009. Report of 2008 Cultural Resource investigations along three sections of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail, Yellowstone National Park. Report submitted to the National Park Service by the Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist. Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Eakin, D.H. 2012a. Report of 2010 Cultural resources investigations along five sections of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail, Yellowstone National Park. Report from Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Laramie, to Yellowstone Park Foundation and Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Eakin, D.H., B.C. Vivian, D. Mitchell, and K. Thorson. 2012b. An archaeological survey and assessment of four locales associated with the Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park in the summer of 1877. Report from Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Laramie, to Yellowstone Park Foundation and Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Eakin, D.H. 2014, 2015, and 2017. Investigations at 48YE506 Nez Perce National Historic Trail, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Report from Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Laramie, to Yellowstone Park Foundation and Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Fisher, S. 1896. Journal of S.G. Fisher, Chief of Scouts to General O.O. Howard during the campaign against the Nez Perce Indians, 1877. Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana, Helen, Montana, USA.

Greene, J.A. 2000. Nez Perce summer, 1877: the U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo crises. Montana Historical Society Press, Helena, Montana, USA.

Greene, J.A. 2010. Beyond Bear’s Paw: the Nez Perce Indians in Canada. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, USA.

Haines, A. 1997. The Yellowstone story: a history of the first national park. volume 1. Colorado Associated University Press and Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Heite, E.F. 1990. Archaeological data recovery on the Collins, Geddes Cannery Site. Report submitted to the Delaware Department of State, Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, Bureau of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Prepared for Delaware Department of Transportation Division of Highways Location and Environmental Studies Office, Dover, Delaware, USA.

Heite, L.B., and E. F. Heite. 1989. Archaeological and historical survey of Lebanon and Forest Landing Road 356A North Murderkill Hundred, Kent County, Delaware. Delaware Department of Transportation Archaeology Series Number 70. Report submitted to the Delaware Department of State, Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, Bureau of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Prepared for Delaware Department of Transportation Division of Highways Location and Environmental Studies Office, Dover, Delaware, USA.

Hunn, E. S., N. Turner, and D. French. 1989. Ethnobiology and subsistence. Pages 525-545 in W.C. Sturtevant and D. E. Walker, Jr., editors. Handbook of North American Indians: volume 12, Plateau. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA.

Johnson, A. 2006. Nez Perce research design. Manuscript. Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

King, J. and D. Eakin 2013. Tree-ring evidence of an 1877 Nez Perce bivouac in Yellowstone National Park. Report prepared for the Yellowstone Park Foundation and the National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Denver, by the Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist,

Lewis, B.R. 1972. Small arms ammunition at the International Exposition Philidelphia, 1876. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology 11. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA.

McChristian, D. C. 1995. The U.S. Army in the West, 1870- 1880: uniforms, weapons, and equipment. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, USA.

McChristian, D. C. 2007. Uniforms, arms, and equipment: The U.S. Army on the western frontier, 1880-1892. volume 1: headgear, clothing, and footwear. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, USA.

McWhorter, L. V. 1992. Hear me, my chiefs, Nez Perce history and legend. R. Bordin, editor. Fourth edition. The Caxton Printers, Caldwell, Idaho, USA.

National Park Service. 2006. Interim project report. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, to Yellowstone Park Foundation, Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Nerburn, K. 2005. Chief Joseph and the flight of the Nez Perce: the untold story of an American tragedy. HarperCollins, New York, New York, USA.

Norris, P.W. 1880. Annual report of the Superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Report to the Secretary of the Interior, for the Year 1880. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., USA.

Scott, D. D. 1994. A sharp little affair: the archaeology of the Big Hole Battlefield. Reprints in Anthropology 45. J&L Reprint Company, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Scott, D. D. 2001. Archaeological reconnaissance of Bear Paw Battlefield, Blaine County, Montana. Technical Report No. 73. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, Midwest Archaeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Sharfstein, D. J. 2017. Thunder in the mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W.W. Norton, New York, New York, USA.

Smith, R. W. 1976. Richardson and Robbins Cannery, 1881 (HAER D-3). Historical American Engineering Record, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., USA. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/de/de0000/ de0010/data/de0010data.pdf

Spang, A., Joseph Walks Along, and Alberta American Horse Fisher. 1999. Cheyenne memories of Little Bighorn. Pages 33- 51 in H.J. Viola, editor. Little Bighorn remembered: the untold Indian story of Custer’s last stand. Times Books, New York, New York, USA.

Sucec, R. 2006. Notes from visit of elders of the Nez Perce Tribe to view artifacts and selected sites from the August 2006 YPF survey. Appendix A in D.H. Eakin, B.C. Vivian, D. Mitchell, and K. Thorson, editors. An archaeological survey and assessment of four locales associated with the Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park in the summer of 1877. Report from Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Laramie, to Yellowstone Park Foundation and Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Swetnam, T. W. 1984. Peeled ponderosa pinetrees: a record of inner bark utilization by Native Americans. Journal of Ethnology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Thwaites, R. G., editor. 1904. Original journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806. volume 3. Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, New York, USA.

White, K. 2007. Notes from visit to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation: meeting with Chief Joseph Band Elders. Appendix B in D.H. Eakin, B.C. Vivian, D. Mitchell, and K. Thorson, editors. An archaeological survey and assessment of four locales associated with the Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park in the summer of 1877. Report from Office of the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Laramie, to Yellowstone Park Foundation and Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

White, T. 1954. Sacred trees in western Montana. Montana State University Anthropological and Sociological Papers No. 17. Bozeman, Montana, USA.

Wilfong, C. 1990. Following the Nez Perce Trail: a guide to the Nee-Me-Poo National Historic Trail with eyewitness accounts. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Part of a series of articles titled Yellowstone Science - Volume 26 Issue 1: Archeology in Yellowstone.

Next: Archeology Facts

Last updated: June 21, 2021