Part of a series of articles titled Yellowstone Science - Volume 26 Issue 1: Archeology in Yellowstone.

Article

A Look Back, Howard Eaton's Yellowstone Tour

Howard Eaton's Yellowstone Tour

by Judith Meyer

Howard Eaton was one of Yellowstone National Park’s (YNP) most famous and beloved concessioners who introduced hundreds of tourists to the wonders of Yellowstone between 1883 and 1921, and whose saddle-horse tours contributed to Yellowstone’s popularity during the park’s formative years. In 1923, one year after Eaton’s death, the National Park Service (NPS) named a newly-completed, 157-mile bridle and hiking trail for him. The Howard Eaton Trail dedication ceremony was attended by movers and shakers from throughout the ranks of national, regional, and local government, attesting to Eaton’s wide notoriety and respect.

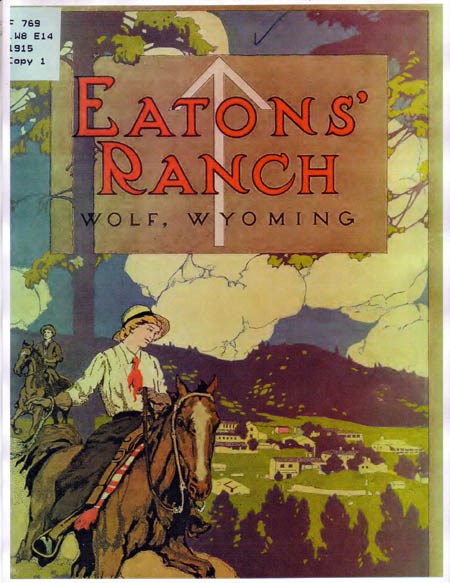

Eaton’s clients were wealthy, educated Easterners who traveled by railroad to Gardiner, MT, and then spent the next two weeks on horseback with Eaton as their guide. They slept in tents and ate their meals outside—a Yellowstone experience very different from the more typical one of traveling by stagecoach, sleeping in hotels, and eating in dining rooms. Howard Eaton’s colorful marketing brochures promised his guests they would be “roughing it with comfort” while enjoying “a harmony of wilderness and civilization” on the trail. Even a quick glance at Eaton’s brochures reveals his keen understanding of what Easterners wanted of a Western experience; appealing to their sense of adventure and desire to spend time outdoors reliving the rugged frontier, but with all the convenience and safety of civilization.

If Eaton and his tours were so popular, what was it like to travel with Eaton? Where does Eaton’s trail-ride-tourism fit in to the broader context of a “Yellowstone experience” and a unique “sense of place” for Yellowstone as a national park? These are questions for historical and humanist geographers. Geographers study not only the environmental and cultural characteristics of locations on Earth’s surface but the personal, human response to those places as well. This “sense of place” describes how people experience a place as a combination of their own real experiences in combination with their expectations of what that place means (Tuan 1975).

Yellowstone has three qualities that make it an especially good study site for understanding sense of place. First, it has a rich history of meanings as a result of its almost 150 years as a national park (Meyer 1996). Second, much of Yellowstone’s historical record has been preserved not only on the landscape, but in the museum and archives at the Heritage Research Center (HRC). Hence, evidence of people’s experiences in the park have been preserved, catalogued, and made available for study. Third, studying people’s sense of place for Yellowstone has value. Yellowstone’s managers have the unenviable task of trying to make Yellowstone serve the needs of many different publics. Understanding how and why people feel the way they do about the park can help inform management decisions.

A Photo-Essay: Experiencing Eaton’s Yellowstone

Eaton’s brochures are a telling source of information about his tours, but only from a business or marketing perspective, providing logistical information about his tours and showing his keen understanding of his market. However, details of a day-to-day Eaton tour through Yellowstone remain a bit of a mystery. Because Eaton’s customers were members of the upper class, it is surprising that so few left written record of their travels. One of only a few existent narratives is “When I Went West” by Robert McGonnigle, included in Whittlesey and Watry’s Ho! For Wonderland (2009). Given this paucity of written narratives, the HRC’s photographic record becomes all the more important. What follows is a photo-essay constructed from seven photographs of Eaton and his clients. The photograph captions come from the original photographs assembled into a photo album under the call number YELL 130117 in the HRC museum. All photographs are provided courtesy of the NPS in YNP and were made available with the patient and professional help of Curator Colleen Curry.

Eaton’s annual tours to Yellowstone were not small, intimate affairs. Instead, Eaton brought three or four dozen tourists at a time. And, his pack train included at least two horses per client: a trail herd and a camp herd. Eaton must have had to choose his overnight camp sites with attention to plentiful water and grass for his many horses, as well as pleasant surroundings for his guests.

Because Eaton provided tents, bedding, food, and other supplies, he could insist each clients bring only one suitcase, relying on them to make practical and resourceful choices when packing clothes and toiletries:

Although Eaton’s earliest guided tours of Yellowstone allowed only men to participate, after the turn of the 20th century, Eaton made a point of welcoming women. As recorded in photographs and Eaton’s brochures, at least half of Eaton’s clients were women. When Eaton began building his guiding business, the women’s suffrage movement was in its heyday; Eaton positioned himself to benefit from it. His brochures insisted “all ride astride” rather than side-saddle. Eaton reached out to women just as the side-saddle vs. riding-astride debate divided attitudes among women belonging to Eastern equestrian clubs (Miller 1901). Generally, women who wanted to ride astride supported women’s suffrage and were the type who might prefer Eaton’s tours over those provided by the railroad companies. The camp store at the Eaton Brothers’ Ranch (Wolf, WY) carried any number of typical supplies, but not the special split-skirts needed for riding-astride; so Eaton recommended that “Ladies are advised to procure their habit for riding astride” before arriving at the ranch (Eatons’ Ranch 1912).

Eaton may have publically promoted his reputation as a conservationist, especially when it came to wildlife protection; however, his clients engaged in all the same environmentally insensitive tourist activities as other tourists, most of which are not allowed today. As these and other photographs attest, Eaton’s travelers fed bears, sat on delicate thermal features, posed next to erupting geysers, washed their laundry in the hot springs, and tramped across a plank bridge to stand on the Fishing Cone formation. For his small business to succeed in competition with the mass tourism of the railroads, Eaton’s tourists had to see all the usual sights and engage in all the usual activities, as well as enjoy life in camp and on the trail.

As one might imagine for such an active, physically-demanding means of travel, meals were important. Eaton’s portable kitchen traveled in what must have been a specially-outfitted, heavy wagon with extra-large wheels. In this view, at least two stovetops and ovens with tall smokestacks are visible. The cabinet looks specially designed and built to carry pots, pans, dishes, and other utensils required to feed such a large group.

In terms of the meals themselves, there seems to have been a large staff involved in helping set up, prepare, and serve the meals. One of Eaton’s employees, a young woman named Dorothy Duncan recalled:

Breakfast was at 6:00 a.m. and we hit the trail by 8:30. Breakfast included hot mush, pancakes, eggs, and a “pail” of bacon that Uncle Howard personally served to the guests. The kitchen and dining room were large tents…. Long tables covered with oilcloth tablecloths sat on folding sawhorses. The aromas that came from the tents were enticing, and the meals were delicious.... The noon meal consisted of sandwiches...delicious canned fruit, and coffee. Loaves and loaves of bread had to be sliced. Uncle Howard gave me my first lesson in making sandwiches. I was putting butter on one side of the bread only when I felt his hand on my shoulder. “Young lady,” he told me, “my dudes get butter on both sides of the bread” (Duncan in Ringley 2010).

The tops of three oven stove-pipes poke through the canvas tent in several photos, and one photo reveals a large pile of wood stacked between the stoves. Because laws against felling trees for camp cooking were not passed until later, it is assumed Eaton gathered wood in the park for use in cooking meals. Although this photograph shows only men in the “big top” or mess tent, Eaton did hire young women to work for him on his trail rides, at least in the later years. Women helped to put-up and take-down the tents, lay out the mattresses, sheets, and blankets in the women’s tents, and prepare and serve meals.

Clients slept in pyramidal tents Eaton designed for their easy set-up and take-down. At every night’s camp, there was a row of white tents for single women, another row of darker tents for single men, and yet another row for married couples. As explained in the promotional material, “Pyramidal tepee tents of heavy waterproofed canvas with floors of the same material, are provided for every two persons. The bedding, receiving competent care every day, is warm, clean, and comfortable.” If guests needed more room to dress and undress, larger tents served as dressing rooms, and still other tents were provided for “sanitary arrangements” (Eatons’ Ranch 1922).

Beyond the dry logistics and the flowery prose and promises of advertisements, what was the real “experience of place”? Did any of these “city folk” regret spending weeks on a horse, even if they were avid members of riding clubs back home? One answer may lie both in the photographic and written record. In one HRC photo, there is a stagecoach parked in the middle of camp. It is not a kitchen or supply wagon, but a sight-seeing coach, something out-of-place in a camp for saddle-horse tourists. Doris Whithorn, tireless historian of Park County, MT, wrote about Eaton’s tours and noted, “Officially called the ‘Fatigue Coach,’ this vehicle was dubbed the ‘Sore-ass Wagon’ by those who herded the guests. Any dude who became weary of the horseback trip on the trail could dismount and wait by the road” for the Fatigue Wagon (Whithorn 1969).

Understanding Howard Eaton’s role in shaping public expectations of not only a national park experience but a Yellowstone experience can help managers grasp the complex ways people respond to the Yellowstone landscape. Common sense would suggest traveling on horseback, sleeping on mattresses on the ground, and using tent latrines instead of bathrooms would be a less attractive way to tour Yellowstone than a stagecoach-hotel-dining room option, especially for those able to afford both. Yet Eaton’s clients endured whatever privations life required, and praised Eaton and the experience he provided because they felt justly rewarded. “Experiencing the Yellowstone” was worth the effort. Understanding the many different ways people appreciate their time in the park should be good news for the NPS. Certainly more and more voices call for better or more tourist services every year, but it is important to understand the motivation calling for more amenities. If Howard Eaton’s approach to providing a satisfying Yellowstone experience is any indication, what people want is an appropriate and meaningful experience, more than a comfortable one.

Literature Cited

Eatons’ Ranch. 1912. Eatons’ Ranch Wolf Wyoming. Eaton Brothers, Wolf, Wyoming, USA.

Eatons’ Ranch. 1922. Eatons’ Ranch Wolf Wyoming. Eaton Brothers, Wolf, Wyoming, USA.

Meyer, J. 1996. The spirit of Yellowstone: the cultural evolution of a national park. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland, USA.

Miller, E. 1901. Should women ride astride? Munsey’s Magazine July:553-557.

Ringley, T. 2010. Wranglin’ notes: a chronicle of Eatons’ Ranch, 1879-2010. Pronghorn Press, Greybull, Wyoming, USA.

Tuan, Y. 1975. Place: an experiential perspective. Geographical Review 65:151-165.

Whithorn, D. 1969. Wrangling dudes in Yellowstone. Frontier Life 43:18-22.

Whittlesey, L., and E. Watry. 2009. Ho! For wonderland: travelers’ accounts of Yellowstone, 1872-1914. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Last updated: April 10, 2019