Part of a series of articles titled Yellowstone Science - Volume 26 Issue 1: Archeology in Yellowstone.

Article

A Look Back, Botanical Adventures in Yellowstone, 1899

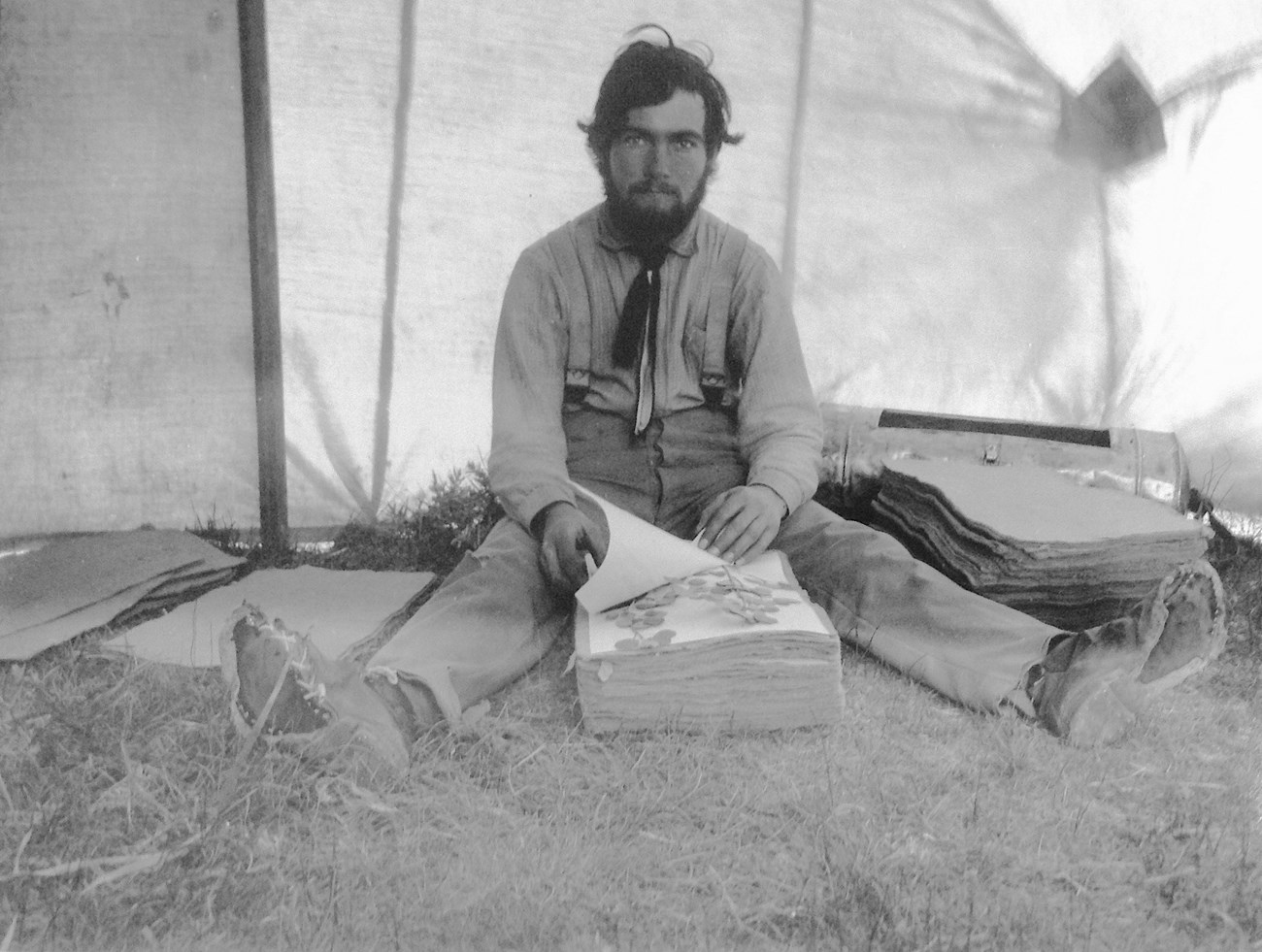

Aven Nelson Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Botanical Adventures in Yellowstone, 1899

by Hollis Marriott

On June 24, 1899, a sentry on routine patrol discovered a party of six camped on the Madison River just inside Yellowstone National Park (YNP). Inspection revealed multiple infractions. In her diary, Mrs. Aven Nelson, a member of the party being inspected, recalled the event:

He was appalled to see so many papers on the ground and demanded that they be picked up at once … There ensued much talk about rules and regulations, in the course of which he discovered that we carried two rifles. After sealing both, he insisted that the signature of Captain Brown would be prerequisite (excerpts from Mrs. Nelson’s diary are from Williams, 1984, who “abbreviated and paraphrased” them).

The soldier was shown a letter from the Acting Superintendent of the park, but was not persuaded. The campers picked up the felt papers they had carefully arranged in the sun, and drove 46 miles to Mammoth (two days travel) where they obtained a permit (Army Era records, YNP Archives). Professor Nelson, his family, and two student assistants were in the park ostensibly to document the flora (plant species). But Nelson had grander plans. By the time they left in early September, they had collected, pressed, and dried 30,000 specimens. The project would launch the Rocky Mountain Herbarium at the University of Wyoming—Nelson’s greatest legacy.

An Accidental Botanist

In July of 1887, 28-year-old Aven Nelson came to Laramie, Wyoming Territory, to be Professor of English at the new University of Wyoming. But the Board of Trustees had mistakenly hired two English professors, so Nelson agreed to teach botany and biology instead. Apparently the six lectures on plants he attended at the Missouri Normal School, and his biology teaching assistantship at Drury College, qualified him for the job (Williams 1984).

It was a fortunate change in profession. Wyoming’s flora was still poorly known, with abundant opportunities for discovery and academic advancement. Nelson’s career would be long and productive. He remained active in botany at the University of Wyoming almost until his death in 1952, at age 93.

A Botanical Expedition of Vast Importance

In the fall of 1898, extraordinary news spread across campus. The excitement was still fresh in Leslie Goodding’s mind 59 years later:

A botanical expedition of vast importance was planned for the following summer. Some three or four months were to be spent in Yellowstone Park collecting plants … Many students, juniors and seniors, were anxious to accompany Dr. Nelson on that expedition, and were willing to work for nothing just to see the Park … this was in the days when autos were much like hen’s teeth and trips through the Park by stage were expensive (Goodding 1958).

Nelson hired 19-year-old Goodding as a field assistant and chore boy, at $10 per month and all expenses paid. The other assistant was Elias Nelson, Nelson’s first graduate student and no relation (Williams 1984).

Nelson wrote to the park requesting permission to collect plants “to represent the vegetation of the Park in full … dried specimens of the smaller plants and such twigs of the larger as may conveniently be preserved on the usual herbarium sheets, 12 x 16 inches.” An affirmative reply came within the month (Army Era records, YNP Archives).

He also contacted botanist P.A. Rydberg, who was preparing a Catalogue of the Flora of Montana and the Yellowstone National Park (Rydberg 1900). Rydberg replied, explaining what Nelson most likely already knew (Rydberg 1898-1899):

The flora of the park is, however well worked up as several collectors have been in there, viz., the Hayden Survey, C.C. Parry, Letteman, Burglehous, &c. The one that has done the most, however, is Frank Tweedy of U.S. Geological Survey. He spent two whole summers in the park.

Rydberg recommended Nelson focus on unexplored areas: “I would advise you to select the mountains east and south east of Yellowstone Lake. None of the collectors that I know of has collected in that region. Tweedy only touched it at the south end of the Lake.”

To Yellowstone—for Adventure & Science

On June 13, 1899, botany students Leslie Goodding and Elias Nelson arrived by boxcar in Monida, Montana, then the western gateway to YNP. They unloaded a wagon, three horses, provisions and gear, including six plant presses and several thousand “driers and white sheets” (Goodding 1944). Two days later, their mentor, Professor Aven Nelson, his wife Allie (Celia Alice), and their two daughters arrived by passenger train. It was the start of a 14-week botanical adventure in Yellowstone.

They left Monida on June 19, traveling east up the valley of the Red Rock River where they did their first collecting. “As we approached the Continental Divide and the Idaho line, we were impeded by mud, and the wagon had to be unloaded to get it free,” noted Mrs. Nelson. The next day they crossed the Continental Divide into Idaho, camped near Henry’s Lake, collected the following morning, and moved on, entering the park on June 23 (descriptions of field work in the park are from Williams 1984, unless noted otherwise).

For the expedition, Nelson purchased a 12 x 14 ft. canvas tent with a stout ridge pole and a reinforced hole for the stove chimney. “For twelve consecutive weeks, no one slept under a roof other than the tent, and the two boys usually under the vaulted star-studded skies” (Nelson ca. 1937).

They could legally camp wherever they wished, as long as they were at least 100 ft. from roads. Park regulations required they leave their campsite “clean, with trash either buried or removed so as not to offend other visitors.” Hanging clothing, hammocks, and other articles within 100 ft. of a road was banned, as was bathing without suitable clothes (Culpin 2003).

Most days they broke camp early and traveled park roads, stopping at promising sites. The men went out to collect, each with a vasculum over his shoulder—an oblong metal container (today we use plastic bags). Many plants were collected in their entirety, but for larger species they took parts—a section of stem with leaves, another with flowers, fruit if available.

In late afternoon, they would look for a suitable campsite with water, firewood, a flat spot for the tent, and grass for the horses. Plant processing began as soon as the tent was pitched and materials unloaded, often continuing into evening.

Plants were pressed and dried, using felt blotters to absorb moisture. Each specimen was carefully arranged between sheets of white paper and added to a growing stack alternating with blotters. Then the stack was tightly bound between wooden covers. The next day, presses were taken apart, damp blotters replaced, and presses reassembled. This continued daily until the specimens were dry.

Nelson had brought several thousand reusable blotters, but maintaining an adequate supply of dry ones was difficult. Ideally damp blotters were spread out to dry in the sun. But when it rained for days at a time, they kept a fire going all day in the tent, with plant presses and blotters carefully arranged around the stove.

They mainly collected near roads, even though earlier collectors had done the same (Goodding 1944). Occasionally two men made long excursions on foot while the third stayed with Mrs. Nelson and the girls. Notably, they did not collect in the unexplored country recommended by Rydberg. Why did Professor Nelson ignore obvious opportunities for discovery? Lack of roads probably was a factor. But there was another consideration: By the time they reached the southern part of the park, they were short one man.

On July 26, Elias and Leslie were collecting near the popular Artist Paint Pots, where visitors were routinely warned to stay on established paths (Guptill 1892-1893). Elias wandered off anyway, sinking one leg in hot mud to the knee. He jumped to higher ground and pulled off his shoe and sock, along with a large patch of skin. A huge blister ran up his leg.

“With the help of several nearby tourists, I sprinkled the wound with soda, bandaged it, and covered the bandage with flour,” wrote Mrs. Nelson in her diary. “Elias was in great pain, but never uttered one groan.” At the Upper Geyser Basin, a visiting physician examined the burn and recommended Elias go to the hospital at Fountain or return home. So Professor Nelson drove him to Madison, where Elias took the stage to Monida, understandably disappointed his great adventure was over.

In early August, impassable muddy roads forced a two-day layover at Yellowstone Lake. When the weather improved, they drove south to the Teton Range, where Nelson and Goodding collected alpine plants for the first time on the trip. Then it rained for a week. Snow fell on August 19. By the end of August, the Nelsons were ready to go home. They reached Monida on September 3, making scattered collections en route, and two days later were back in Laramie.

The Adventure Ends, But the Science Continues

In 14 weeks they collected roughly 30,000 specimens (Williams 1984)—an astounding number given the conditions, yet only about 500 species were represented (Rocky Mountain Herbarium 2015; precise number is unknown due to subsequent changes in classification and nomenclature). Most of the specimens were duplicates—multiple collections of a given species from a given site. Clearly, documenting the flora of YNP was not Nelson’s primary objective. He was intent on expanding the botany program at the University of Wyoming, specifically the herbarium (the same conclusion was reached in Williams 2003).

With just 1,500 specimens, the herbarium offered little prior to the Yellowstone project. That changed dramatically—1,400 specimens were added directly and thousands more through exchange. Nelson knew institutions and collectors would want specimens from Yellowstone, the famous natural wonderland, and he collected accordingly—often 20-30 duplicates per species per site (Nelson ca. 1937). A full set of duplicates went to the U.S. Herbarium at the Smithsonian (the park had no herbarium at that time). Smaller sets were distributed across the U.S., in Europe, and as far away as India, in exchange for equal numbers of specimens for Nelson’s herbarium. Sets also were sold to raise money for field work (Williams 1984), a practice no longer permitted by the National Park Service or the University of Wyoming.

Shortly after returning from Yellowstone, Nelson convinced the Board of Trustees to designate a separate institution for the plant collection—the Rocky Mountain Herbarium. They intended it to be “an accessible and serviceable collection” of the region’s plants, but it has far exceeded their expectations. At 1.3 million specimens, it is now the tenth largest herbarium in the U.S.

We call Aven Nelson the Father of Wyoming Botany, a delightful irony given that he became a botanist by bureaucratic error. In his long career, he collected many thousands of specimens (not counting duplicates), described numerous new species, published more than 100 academic articles, and mentored students who became prominent botanists themselves. But his greatest legacy is the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, a world-class institution built on a foundation of Yellowstone plants.

The park now has its own herbarium, considered an untapped gem. Established in 2005 in the park’s Heritage and Research Center, the Yellowstone Herbarium contains over 17,000 specimens of vascular and non-vascular plants, fungi, and lichens. The aquatic plants collection is particularly extensive. The herbarium is available to visitors and scientists alike, for research or tour. Herbaria were originally invented to help people identify plants suitable for gardening and propagation. Today’s herbaria, however, document current species distributions, as well as aid with plant identification. The Rocky Mountain Herbarium and Yellowstone Herbarium are prime examples of the United States’ prominent herbaria.

Literature Cited

Culpin, M.S. 2003. For the benefit and enjoyment of the people: a history of the concession development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872–1966. YCR-CR-2003-01. Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Mammoth, Wyoming, USA.

Goodding, L. 1944. The 1899 botanical expedition into Yellowstone Park. University of Wyoming Publications 11:9-12.

Goodding, L. 1958. Autobiography of the Desert Mouse. San Pedro Valley News, June 26.

Guptill, A.B. 1892-93. All about Yellowstone Park: a practical guide. F.J. Haynes, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA.

Nelson, A. ca. 1937. The Rocky Mountain Herbarium (typed manuscript). University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center, Aven Nelson Collection, Laramie, Wyoming, USA.

Rocky Mountain Herbarium. 2015. Specimen database. University of Wyoming. http://www.rmh.uwyo.edu/data/search.php

Rydberg, P.A. 1898-1899. Letters to Aven Nelson. University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center, Aven Nelson Collection, Laramie, Wyoming, USA.

Rydberg, P.A. 1900. Catalogue of the flora of Montana and the Yellowstone National Park. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 1:1-492.

Williams, R.L. 1984. Aven Nelson of Wyoming. Colorado Associated University Press, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Williams, R.L. 2003. A region of astonishing beauty: the botanical explorations of the Rocky Mountains. Roberts Rinehart Publishers, Lanham, Maryland, USA.

Last updated: April 10, 2019