Photograph from Stephen Foster Collection, 69-92-334. University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives.

Management directives for Denali National Park and Preserve (Denali) stipulate that traditional lifeways and historic and contemporary activities of Alaska Native peoples be considered in the decision-making process. This article illustrates the types of information documented in recent research that can assist park officials in fulfilling this important mandate.

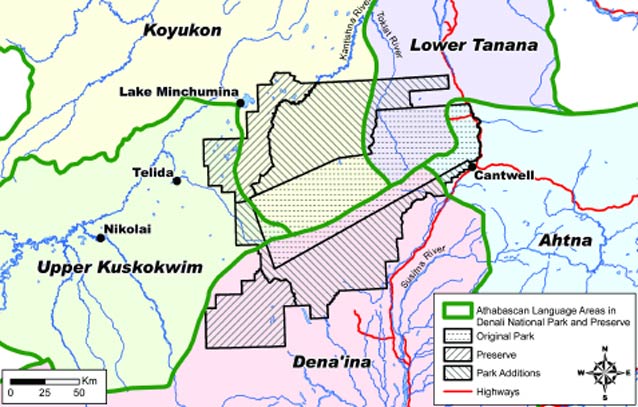

The area in and around Denali comprises part of the aboriginal homeland of five Northern Athabascan Indian groups—Dena’ina, Koyukon, Lower Tanana, Upper Kuskokwim, and Western Ahtna. The affiliation of five Native groups with one national park is unique and illustrates the rich and diverse cultural heritage of the Denali area.

The long-term use and occupancy of the area by these five groups is confirmed by examining the areas to which they assigned place names. The linguist James Kari (1999) assembled more than 1,650 names that these groups gave to geographic features within a 100-200 mile (161-322 km) radius of the summit of Mt. McKinley. Many of these names are associated with landmarks located on or near rivers and streams (Figure 1).

Sociopolitical Organization

Like most hunter-gatherer peoples, Denali area Athabascans lived in small, autonomous groups comprised of close relatives. Political organization was decentralized and informal; most decisions affecting the group were reached by consensus. An exceptional man might exert his authority over the group, but people followed his decisions only if they considered doing so to be in their best interests.

Kinship ties extended beyond the immediate group and provided people with a network of relatives from which assistance could be obtained when resources were scarce. Descent was matrilineal so a child belonged to their mother’s clan. Households typically consisted of two related families who shared a dwelling and functioned as a single economic unit. For much of the year, people lived in small aggregates referred to as the local band, which was a large extended family centered around a core group of siblings, their spouses, children, and other close relatives. Band size varied but usually numbered from 20-75 people. Two or more local bands in the same area often joined forces to harvest fish and wildlife. This larger group, or regional band, had as many as 200-300 members who were linked by kinship ties and language dialect.

Band Territories in the Denali Area

Regional bands were associated with a specific territory shaped by the drainage pattern of a major waterway. On the south side of the Alaska Range a Dena’ina band called the Susitnuht’ana or Susitna River people, used an area extending north from the mouth of the Susitna River to the Alaska Range and Talkeetna Mountains, while a mixed band of Dena’ina and Ahtna, called the “mountain people,” exploited the Talkeetna River drainage. The home territory of the Western Ahtna included the Broad Pass area and upper Nenana River corridor. One Lower Tanana band had a territory that included most of the drainages of the Nenana and Toklat rivers. Several Upper Koyukon bands inhabited the Kantishna River drainage from the Tanana River south to Denali and from the Toklat River east to Lake Minchumina.

Life Cycle

An Athabascan child was educated to become a skilled hunter or an industrious and accomplished housewife. Rigorous training began at puberty and included the strict observation of rules to ensure good health and a long life. Compliance, especially by young women during their first menses, also protected the community by assuring good luck and removing pollution that would drive away game animals.

Training for young men focused on physical conditioning and acquiring practical skills, spiritual power, and values necessary to become a good provider. Fathers initially trained their sons, but this responsibility eventually shifted to the maternal uncle because children belonged to the mother’s clan.

Young women experienced equally demanding training, which began with a year of isolation from the family dwelling at the onset of menses. During this time female relatives provided food and instruction in sewing and proper behavior. Following a year of seclusion, young women were eligible for marriage and frequently married older men. A wealthy man might have more than one wife, the eldest of whom usually had seniority and supervised the younger wives.

People usually married outside of their local band but within the regional band. Among the Ahtna, a wealthy man reinforced his political standing by marrying women from different family groups; in doing so, he attracted followers —and especially brothers-in-law, who acted as his retainers. Marriage between cross-cousins (i.e., children of a brother and of a sister) was preferred because such alliances created bonds between widely dispersed groups.

Making a Living

Prior to European contact, Athabascan groups in Alaska moved seasonally within a defined territory to procure food resources and materials to make tools, clothing, and shelter. Because starvation was always a possibility, flexibility and specialization characterized the Athabascan bands that sought resources in the Denali area. If one resource was in short supply, efforts were redoubled to find alternatives.

The annual cycle of Upper Kuskokwim bands illustrates the importance of the Denali area for survival. People traveled by toboggan from winter camps to the Alaska Range foothills and LakeMinchumina areas in the early spring to harvest caribou, moose, bear, sheep, waterfowl, and fish. Two or more bands often collaborated to drive caribou into fences or surrounds, where they then dispatched the animals. Some of the harvest was cached and in the late fall transported by skin boats back to winter encampments. Winter activities included ice fishing, harvesting beaver, hare, game birds, and hunting hibernating bears.

Some band members remained at the winter camps throughout the year, where they harvested and processed wild foods. In the spring and summer, they caught several species of whitefish. Waterfowl eggs were gathered and birds captured in nets or killed by bow and arrow. Grizzly bears were taken with spears in the late fall near salmon spawning sites on the upper reaches of tributary streams.

Contemporary Subsistence

As resident zone communities, Nikolai, Telida, Lake Minchumina, and Cantwell are authorized to conduct subsistence activities in some areas of Denali by virtue of having significant concentrations of residents who have customarily and traditionally used these lands for subsistence purposes.

Nikolai become a permanent settlement after a school was established at its present location in the late 1940s. More families moved there after the school in nearby Telida closed in the mid-1990s. In 2002, the population of Nikolai was 96 people and predominately Alaska Native. Only a quarter of the adult population was employed year-round. Today, Nikolai families harvest primarily chinook salmon in June and July, and moose in the fall and winter. They also harvest chum and coho salmon, northern pike, whitefish and grayling, along with game birds and fur-bearing animals such as beaver. Trapping once provided cash income, but changes in habitat have reduced the abundance of fur-bearing animals, and low fur prices and the cost of gasoline have made trapping uneconomical. Caribou are scarce and seldom hunted, and changes in hunting regulations have made Dall sheep hunting difficult.

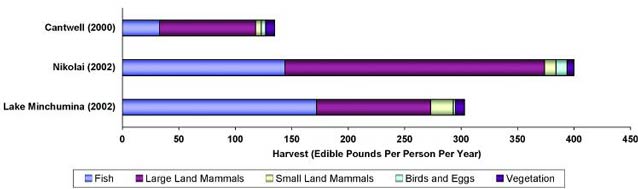

In 2002 the per capita harvest of wild resources in Nikolai was 401 pounds (Figure 2), half of what it was in 1984. Local people attribute this decline to environmental change, competition from non-local hunters, predation by wolves and bears, a change in values, and the high cost of gasoline. Increased competition from sport and commercial fisheries, regulatory prohibition against using a fish trap, and forced use of rod and reel are reasons given for the decrease in salmon harvests. Residents attribute declining chinook salmon stocks to falling water levels and warmer water temperatures. Some Nikolai elders believe that lower chinook harvests are also related to a loss of respect for animals and a decline in sharing and working together. While Nikolai elders believe that not upholding traditional values influences wildlife abundance, they also understand that the current scarcity of moose is a multifaceted problem tied to factors such as predation and competition from sport hunters and subsistence hunters downriver.

Historically, Lake Minchumina was a seasonal camp for staging caribou and sheep hunts in the Alaska Range foothills and for harvesting freshwater fish. In 2002, the population was 25 people, 12% of whom were Alaska Native. The per capita harvest of wild resources totaled 296 pounds, consisting primarily of northern pike, whitefish, moose, and black bear.

Residents say that moose are plentiful but changes in the lake may have long-term consequences for the community. Following the 1964 earthquake, the water level in Lake Minchumina dropped eight feet, and the wetlands surrounding Lake Minchumina drained. The water level fell another two feet in 2002, but it is uncertain whether this decline is related directly to the large 2002 earthquake, since little precipitation was recorded during the winter of 2002-2003 and the following summer. Coupled with the drop in water level, shifting channels in the Foraker River caused large amounts of silt to be deposited into the lake. In 2001, the river shifted back to its normal channel and the lake cleared, but silt deposits created thicker weed beds, which can benefit some species but can reduce oxygen levels in the water and kill fish or convert productive areas into dead habitat.

Cantwell is located at the junction of the George Parks and Denali highways, 211 miles north of Anchorage and 28 miles south of the entrance to Denali. In 2000, Cantwell had a population of 222 people and was 27% Alaska Native. Almost 69% of the adult population was employed sometime in 2000, but only 46% worked year-round. Cantwell residents harvested 135 pounds of subsistence resources per person. Moose are the largest component of the harvest, followed by caribou and sockeye salmon.

Cantwell residents harvest freshwater fish and black and brown bear in the early spring. Freshwater fishing continues in the summer, as does salmon fishing outside the local area. Berry-picking and hunting for Dall sheep and moose begin in mid-August. Caribou hunting begins in the fall and continues in winter and early spring. Other fall activities include hunting for grouse, ptarmigan, and ducks, and silver salmon fishing outside the region. During the winter, residents continue to hunt game birds, trap fur-bearing animals, and ice fish for trout and burbot.

Photograph from Stephen Foster Collection, 69-92-334. University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives.

Feeling squeezed between urban Alaska and the National Park Service, Cantwell residents believe that pressure from urban hunters has caused game populations to decline, especially in areas that locals used traditionally. As a result, many residents now hunt almost exclusively in Denali. Cantwell people emphasize their dependence on hunting and fishing to provide for their families. They consider themselves stewards of the land with knowledge that should be utilized in wildlife management. There is also the view that Cantwell is not wilderness; therefore, Denali and adjacent lands should be managed for tourism rather than as wilderness. Some local people perceive the concept of ecosystem management as an excuse by the NPS to extend its influence beyond park boundaries and create more environmental regulation.

Summary

This article has summarized selected information presented in an ethnographic overview and assessment written for the National Park Service (Haynes et al. 2001) and in baseline studies describing contem-porary subsistence practices in communi-ties affiliated with Denali National Park and Preserve (Simeone 2002, Holen et al. 2005, Williams et al. 2005). These reports should be consulted for more detailed information on the topics discussed here.

References

Haynes, Terry L., David B. Andersen, and William E. Simeone. 2001.

Denali National Park and Preserve: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment. Report prepared by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence, Cooperative Agreement CA 9910-7-0040.

Holen, Davin L., William E. Simeone, and Liz Williams. 2005.

Wild Resource Harvests and Uses by Residents of Lake Minchumina and Nikolai, Alaska, 2001 – 2002. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. Technical Paper No. 296.

Kari, James. 1999.

Draft Final Report: Native Place Names Mapping in Denali National Park and Preserve. Revised draft report prepared for the National Park Service.

Simeone, William E. 2002.

Wild Resource Harvests and Uses by Residents of Cantwell, Alaska 2000. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. Technical Paper No. 272.

Williams, Liz, Chelsie Venechuk, Davin L. Holen, and William E. Simeone. 2005.

Lake Minchumina, Telida, Nikolai, and Cantwell Subsistence Community Use Profiles and Traditional Fisheries Use. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. Technical Paper No. 295.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 5 Issue 1: Scientific Studies in Denali.

Previous: Medical Research Climbs Mount McKinley

Last updated: October 27, 2021