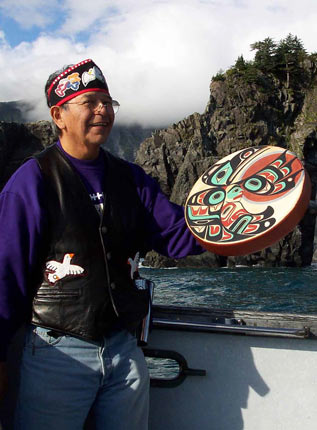

Courtesy Mary Beth Moss

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve contains almost 2.7 million acres of designated wilderness and is one of few national parks that protect wilderness marine waters. The area is also the traditional homeland of two Tlingit tribes; the Gunaaxoo Kwaan who claim the northern coastal reaches and the Huna Kawoo who settled Glacier Bay proper, Icy Strait, and long stretches of the outer coast.

Glacier Bay is like a set of concentric circles of meaning, and to the Tlingit, a community of spirits lie at the very core. The Tlingit Clans have lived in Sít’ Eeti Gheeyí, the “Bay in Place of the Glacier” and along Icy Strait and the outer coast for countless generations; the Tlingit say since time before memory. For them, the vast stretches of wilderness are inhabited places, alive with sentient and non-sentient beings, as well as the spirits of the living and those who have gone before.

Mountains, waterways, rocks, and animals are all imbued with spirits; each is respected as an individual and an equal. A deep and enduring connection with this greater community of life is ingrained in the Tlingit world view and respectful interaction with all beings ensures community health. A traditional Tlingit tale recounts the cataclysmic events that occurred when a young woman spoke disrespectfully to a glacier, and even today, the tribal members respectfully refrain from pointing at the slopes of Mt. Fairweather—Yeik Yi Aaní or “Land of the Spirits.”

Humans have always been an inextricable part of Glacier Bay’s web of life; the Tlingit are as closely connected to the land, the water, and the inhabitants of both as they are to each other. They believe that their continued interaction with homeland is a sustaining—indeed vital—characteristic of this place. The Tlingit come to Glacier Bay Wilderness not to be alone, or to explore a previously unvisited place, but rather to be in communion with ancestral spirits and to retrace the footsteps and actions of all those who have visited before them. In a place that is now called wilderness, the Tlingit people are never alone, but always in the company of their living and nonliving relatives; the bear people, the ice people, and all the spirits of the homeland. While many visitors come to Glacier Bay to witness the spectacle of a whale breaching or a glacier calving, and are understandably awed by nature’s exhibitions, the Tlingit would perhaps experience the whale’s breach and the crumbling ice as communication between the leviathan, the glacier, and their human clan relatives.

Courtesy Mary Beth Moss

Tlingit culture was shaped by, and remains dependent upon, continued interaction with homeland. Gathering food resources is a particularly important traditional activity, as the process of harvesting is not only a means of sustaining physical needs, but also a ritual for reconnecting and engaging with ancestral spirits.

Southeast Alaska’s abundant resources—salmon, halibut, seal, gull eggs, and berries—allowed the Tlingit ample leisure time to develop complex social and political systems as well as sophisticated artistic and ritualistic practices. In essence, Glacier Bay’s rich array of marine and terrestrial foods made the Tlingit who they are—a highly structured society with a well-developed political, social, artistic, and spiritual tradition.

Traditional foods are gathered and eaten not only to sustain the body, but also to sustain the culture itself. Restrictions and regulations that reduce opportunities to hunt, fish, and gather pose a threat not only to traditional diets and ways of life, but to the Tlingit ability to participate in the web of life and connect with the present, past, and future.

The Tlingit concept of at.óowu, meaning “something owned or purchased” is central to traditional people’s relationship to Glacier Bay. When an advancing glacier forced the ancestors from their homeland, a woman remained, sacrificing her life to appease the glacier. Other clans were washed out of Lituya Bay by a tidal wave that decimated their villages and drowned many inhabitants. To the Tlingit, the loss of these precious lives paid for their homeland and the stories, songs, clan crests, and regalia commemorating these losses are the Tlingit “deeds” to place.

The concept of wilderness as defined in the Wilderness Act is a modern construct that emphasizes the value of places with little evidence of human change. But the continued relationship of the Tlingit clans with their homeland is as much a part of the wilderness character of Glacier Bay as the glaciers, the trees, and the opportunity for an unconstrained experience. To some, without Tlingit ties to the spirits and ancestors, the Glacier Bay Wilderness would become like a static museum. Perpetuating the Tlingit language and traditional practices ensures that the spiritual connection to this place is not lost and that the Glacier Bay Wilderness remains a living community.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 1: Wilderness in Alaska.

Last updated: August 29, 2022