Photo by Gino Graziano

Abstract

Throughout Southwest Alaska invasive plants have potential to impact natural resources and ecosystems. Weed management efforts exist on the Kenai Peninsula and Kodiak Archipelago. Areas around King Salmon and Dillingham are developing management programs. Other areas lack awareness of the issue, or struggle to implement effective management. To lessen the threat from invasion in underserved areas, collaborative approaches are needed to educate communities, implement prevention, conduct inventory, and manage invasive plants using integrated pest management practices. Existing cooperative efforts for invasive plant management provide guidance to develop new programs in these underserved communities.

Photo by Gino Graziano

Introduction

Invasive species are defined as introduced species that cause or are likely to cause harm to the environment, human health or the economy (Executive Order 13112). In this context, harm occurs when the benefits of the plant are fewer than the detriments of invasion (NISC 2006). Introductions are typically considered relatively recent events starting with Russian and American contact, and include anthropogenic influence establishment of species not native to the local area, even if it is native to other parts of North America or Alaska.

Highly invasive species are known to impact the resources and biodiversity of infested areas. In Alaska, some invasive plants have demonstrated potential to impact species and resources. White sweetclover, Melilotus officinalis, at high densities can suppress growth of Salix alaskensis on glacial floodplains (Spellman and Wurtz 2010). The European bird cherry, Prunus padus, in Anchorage riparian areas does not support comparable quantity or diversity of insects as native plant communities (Roon 2011), and contains toxins which caused the death of three calf moose during the winter of 2010-2011 (Woodford and Harms 2011). Other highly invasive species are present in Alaska, however research documenting impacts often does not occur until a species is too well established to eradicate.

Not all introduced and spreading species cause harm and are truly invasive. Some will simply integrate into the ecosystems with little consequence, while others are aggressive ecosystem engineers. The process of transitioning from invasion to harm can take many years, commonly referred to as the lag phase, with a plant seeming relatively innocuous before rapid expansion of the species. Once harm is realized from invasion it is often too late to eradicate the species. With 374 introduced plants recorded in Alaska, determining which are highly invasive and deserve management is complicated (AKEPIC 2012).

To help predict the potential harm from an invasive plant, biologists created a ranking system for invasive plants in Alaska (Carlson et al. 2008). The ranking assesses climate suitability to eliminate species unlikely to establish, and evaluates the introduced plants potential to impact an ecosystem. Ranks range from 0-100 where 0 is not invasive and 100 is the most invasive. Utilizing invasiveness ranks, land managers can prioritize multiple species for management in a given area.

Invasive plant introductions occur in a variety of ways. Invasive plants are sometimes deliberately introduced without knowledge of the species’ invasive tendencies. However, with the realization of invasions from deliberate introductions, revegetation with indigenous plant material is increasing in practice. Humans often act as unknowing vectors of invasive species to new areas. Seed, hay/straw, fill material, horticultural products, heavy equipment, vehicles, and even camping equipment commonly used in research base camps all have potential to introduce invasive plant propagules.

The remainder of this article will cover prevention, decision tools to aid in management, areas in need of weed management activities in the Southwest Alaska Area Network (SWAN); and examples of successful weed management programs in the SWAN. There is need for prevention and management of all taxa of invasive species, however, this article will focus on invasive plants.

Photo by Gino Graziano

Prevention

Preventing introductions is the highest priority in effective invasive plant management. The suite of prevention measures commonly revolve around activities that disturb the land and include steps such as; cleaning equipment, using local materials (plant and fill), using certified weed free products (e.g. gravel, hay and straw), and staging camps and equipment in areas that are weed free. While typically used in major disturbance activities, land managers should utilize these same strategies whenever applicable to research camps and other human traffic in remote areas.

Certified weed free products are increasing in availability in Alaska. Focus for certification programs has remained on straw and hay products and also gravel recently. These products are inspected according to standards developed by the North American Weed Management Association (NAWMA). It includes a list of NAWMA prohibited weeds as well as additional weeds specific to Alaska. The certification program is designed to significantly decrease the chance of accidental introduction of the prohibited species, however, species not included on the prohibited list may still be introduced.

Management Decision Tools

When an invasive plant is established, coordinated action to manage the infestation is necessary. Approaching management involves using the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), a common sense approach that aims to successfully manage pests with methods that minimize secondary impacts. Land managers can find assistance in developing sound IPM plans with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Cooperative Extension Service, IPM Program and previously completed agency management plans.

Often multiple infestations of multiple invasive plants are known in an area, and limited funds force a triage approach. In these situations land managers should prioritize the following three themes: 1) Which species are likely to be the most invasive in the landscape? 2) Which infestations present the greatest threat of spread to sensi-tive habitats? and 3) Which infestations present the greatest probability of successful management with available funds?

The ranking system discussed earlier is a key component for prioritizing infestations as it describes the invasiveness of a species (Carlson et al. 2008). Spatial analysis of known infestations can determine which species are too abundant for eradication and which are in closest proximity to sensitive habitats. One approach to spatial prioritization developed by the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge for the Kenai Peninsula Cooperative Weed Management Area (CWMA) prioritizes watersheds and infestations for reed canary grass, Phalaris arundinacea, based on discreteness and isolation (Maupin 2011). The Kenai Peninsula approach considers watersheds that are more discrete and isolated a higher priority for prevention and management when an infestation is found.

USFWS photograph courtesy of Leslie Kerr

Weed Management Needs

Finding and managing infestations with potential to affect resources in the SWAN is difficult. Agencies such as the National Park Service have conducted thorough inventories of park lands to identify priorities. More inventories are necessary in communities near park and refuge lands where inventories are complicated by private lands and expense to visit remote locations. One solution to help find and prevent establishment of infestations in these communities is education and outreach. Education and outreach efforts have uncovered new infestations in remote areas of Alaska and spurred the establishment and local ownership of weed management efforts. Tools for reporting and identification are already developed including a Yup’ik language invasive species guide (Lisuzzo 2011).

The discontinuity and varying organizational capacity of communities in the SWAN creates difficulties in organizing weed management efforts, particularly when management is outside of park boundaries. Still, these infestations are some of the most important to manage, as they are often recently established and isolated.

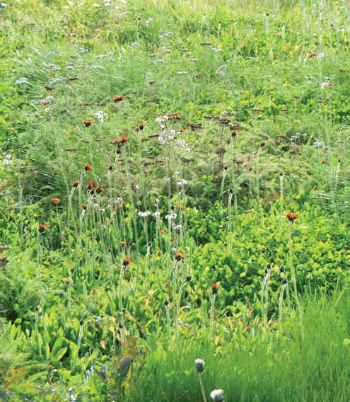

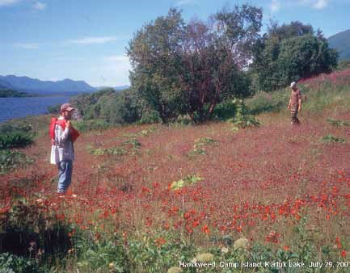

There are three known areas in the SWAN that are in need of increased management efforts to prevent established infestations from spreading to nearby park and refuge lands. Canada thistle, Cirsium arvense (Figure 1), is found in Tyonek and Cold Bay off federal lands. Survey crews visiting Tyonek and refuge staff in Cold Bay discovered the thistle infestations. Canada thistle grows in a variety of habitats including wetland and dry sites. It is capable of forming monocultures when left unmanaged. Orange hawkweed, Hieracium aurantiacum (Figure 2), found on Adak Island off refuge lands is highly aggressive in grass and forb dominated communities. Hawkweed is pollen-allelopathic, preventing seedling establishment of other species (Murphy 2001). Hawkweed can also reproduce asexually (apomixis), making it a highly successful colonizer of new areas, and aggressively spreads vegetatively. These adaptations allow hawkweed to form monocultures in areas that support diverse grasses and forbs.

USFWS photograph courtesy of Bill Pyle

Current Programs

Within the SWAN are a few interagency weed management programs. These include the Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Archipelago, and Bristol Bay area. Each of these programs has a unique strategy to education, outreach and control work, utilizing multiple partners to facilitate implementation of action strategies.

The Kenai Peninsula CWMA consists of many partners including the Kenai Peninsula Borough, three soil and water conservation districts, the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, Chugach National Forest, Cooperative Extension Service and others. Their programs focus on educating the public to manage weeds on their lands, through demonstration projects. They also support work done on refuge and national forest lands providing an avenue for the public to be informed about these weed management activities. Through their work they have successfully eradicated spotted knapweed, Centaurea stoebe (Figure 3), and are nearing successful eradication of Canada thistle.

The Kodiak Archipelago has an active CWMA that has a central partnership between the Kodiak Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) and the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). When the Kodiak NWR completed an Environmental Assessment to use herbicides on infestations they included a process to work off refuge lands with an entity that submits a pesticide use proposal to their program (KNWR 2010). In this way the refuge is able to fund the Kodiak SWCD to manage infestations off refuge lands. The two organizations also partner extensively to provide public outreach and agency education. The Kodiak NWR is managing remote infestations of orange hawkeed and other species on refuge lands (Figure 4).

The Bristol Bay Native Association (BBNA) has established efforts to inventory, manage and educate the public about invasive weeds. The program started with American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds granted to the Alaska Association of Conservation Districts from The U.S. Forest Service. Presently the Ekuk Village Council is leading the efforts. The Bristol Bay weed management group has completed inventory and outreach in six of the area communities. Expansion of inventory, education and control work in the Bristol Bay area is supported through a grant from the Western Alaska LLC to hire technicians and inventory and educate the residents of 26 more villages.

Conclusion

Invasive species are best managed now before problems are realized. Implementing sound prevention, education, and inventory are necessary for early successful management.

References

Alaska Exotic Plant Information Clearinghouse (AKEPIC). 2012. Non-Native Plant Species List. Accessed January 27, 2012.

(http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu/botany/akepic/non-native-plants-alaska)

Carlson, M.L., I.V. Lapina, M. Shephard, J.S. Conn, R. Densmore, P. Spencer, J. Heys, J. Riley, and J. Nielsen. 2008. Invasiveness ranking system for non-native plants of Alaska.

USDA Forest Service, R10-TP-143. Accessed January 26, 2012.

(http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu/botany/akepic/publications)

Executive Order 13112. Invasive Species Info. Accessed January 26, 2012.(http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/laws/execorder.shtml)

Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge (KNWR). 2010. Environmental Assessment- Integrated pest management of invasive plants on Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge and Vicinity. Accessed January 26, 2012. (http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu/botany/akepic/publications)

Lisuzzo, Nicholas. 2011. Protecting Southwestern Alaska From Invasive Species: A Guide in the English and Yup’ik Languages. Forest Service Alaska Region. R10-PR-024.

Maupin, Brian 2011. Reed Canarygrass Management on The Kenai Peninsula: A Spatial View. Presented at the 12th Annual Alaska Invasive Species Conference, October 19-21, 2011. Accessed January 26, 2012.(http://www.uaf.edu/ces/pests/cnipm/otherresources/12th-annual-proceedings)

Murphy, Stephen D. 2001. The Role of Pollen Allelopathy in Weed Ecology. Weed Technology 15(4): 867-872.

National Invasive Species Council (NISC). 2006. Invasive Species Definition Clarification and Guidance White Paper. Definitions Subcommittee of the National Invasive Species Council. Accessed January 26, 2012.(www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/council/isacdef.pdf)

Roon, David A. 2011. Ecological effects of invasive European bird cherry (Prunus padus) on salmonid food webs in Anchorage, Alaska streams. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Spellman, Blaine T., and Trish L. Wurtz. 2010. Invasive sweetclover (Melilotus alba) impacts native seedling recruitment along floodplains of interior Alaska. Biological Invasions 13(8): 1779. Accessed January 26, 2012. (doi: 10.1007/s10539-010-9931-4)

Woodford, Riley, and C. Harms. 2011. Cyanide-poisoned Moose Ornamental Chokecherry Tree a Devil in Disguise. Alaska Fish and Wildlife News. March 2011. Accessed January 27, 2012. (http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_

id=501&issue_id=96)

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 11 Issue 2: Science in Southwest Alaska.

Last updated: June 13, 2016