USGS https://libraryphoto.cr.usgs.gov/htmlorg/lpb085/land/mgc00747.jpg

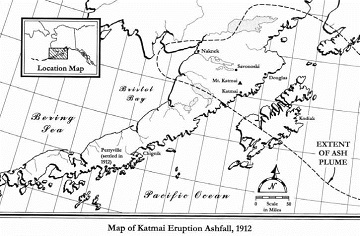

The eruption of Novarupta Volcano near Katmai on June 6, 1912 was a well-documented disaster that destroyed the villages of Katmai (Figure 1), Douglas, and Savonoski, as well as a number of fish camps on the Alaska Peninsula and a commercial salmon saltery at Kaflia Bay. To the inhabitants, the eruption marked an abrupt end to the old way of life. To anthropologists, actions taken in response to the eruption exposed and tested the resilience of the local culture and society.

This article discusses the explosion and its aftermath in the context of the anthropological theory of disaster. According to this theory, geological events happen to the earth, disasters to its inhabitants. The former is a natural occurrence while the latter entails destruction of human life and belongings, disruption of the social fabric, and interruption of customary commerce and government. Anthropologists Oliver-Smith and Hoffman explain:

The conjunction of a human population and a potentially destructive agent does not inevitably produce a disaster. A disaster becomes unavoidable in the context of a historically produced pattern of “vulnerability,” evidenced in the location, infrastructure, sociopolitical organization, production and distribution systems, and ideology of a society (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2002).

NPS photograph

The authors explain what can be gained by examining disasters:

Disaster exposes the way in which people construct or ‘frame’ their peril (including the denial of it), the way they perceive their environment and their subsistence, and the ways they invent explanation, constitute their morality, and project their continuity and promise into the future (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman 2002).

Disaster studies were first undertaken in the 1950s, then reframed in the 1990s as social scientists moved beyond descriptions of static cultures to considerations of the dynamics of culture change. The result was the theory of social vulnerability. Briefly stated, a community’s vulnerability is its capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impact of a cataclysmic event (Blaikie et al. 1994). The vulnerability profile of a community can be understood as a set of pre-adaptations, or practices and understandings that prepare people to deal with environmental disruptions.

Another outcome of disaster research has been a description of a range of predictable responses. These begin with an examination of the belief system, resulting in either a reaffirmation, with modifications to accom-modate the new reality, or a recanting and replacement of the old system. Disasters unmask existing ties and cleavages in social alliances, and can instigate new ones. In complex societies, disasters are often occasions for readjusting the relationship between local people and the structures of the larger society. Finally, survivors assign meaning to disasters. A common response is to ascribe a cause related to human action or supernatural design, such as divine retribution for sins committed, or as a warning to people who have disregarded Nature’s power. Another response is to consider disasters beyond understanding, acts of nature that are random, outside the realm of justice, and devoid of meaning.

This article will explore the responses of the Katmai Sugpiat as a contribution to an understanding of both this particular disaster and disaster theory in general.

Historical Context

Throughout history, the Sugpiat of the Alaska Peninsula had been a mobile people, recognizing a network of kinship with people up and down both coasts of the peninsula and Kodiak Island. Communities were formed, abandoned, and reinhabited over and over again (Partnow 2001). People moved about because of availability of resources, opportunities for cash income, and family dynamics such as marriage and feuds. They knew the resources of the land and sea.

The villages of Katmai and Douglas had been established as trading posts by the Russian-American Company during the nineteenth century. About ten years before Novarupta exploded, the two trading posts had closed, leaving the villages as backwaters rather than economic centers. Only a year before, the entire sea otter hunt had been halted under the International Fur Seal Treaty. The economy that had sustained the people for more than a century had suddenly collapsed. Meanwhile, salmon canneries in Chignik and Bristol Bay had drawn most of the peninsula’s population south and west. The 1910 US Census lists the following populations for settlements on the Alaska Peninsula, a clear indication of the new importance of Chignik as a population center: Douglas - 45, Katmai - 62, Cold (Puale) Bay - 11, Kanatak - 23, Chignik - 565, Mitrofania - 27, Savonoski - 32. Much of this population growth consisted not of Sugpiat, but newly arrived Scandinavians and seasonally imported Asian workers. Alaska Native workers accounted for only a tiny proportion of the workforce, since the large canneries refused to employ Alaska Natives as late as 1910 (cf. Porter 1893, Davis 1986) (Figure 3).

Kodiak Historical Society

The residents of Katmai and Douglas had fallen back on subsistence practices, but they were still able to find work with a commercial fishing saltery at Kaflia Bay. People had come to consider this a regular part of their seasonal round, as evidenced by the sod houses, locally called “barabaras,” that they built near the saltery.

Like the economy, the social system that had held sway in Katmai and Douglas was in flux in 1912. For 100 years, these villages had been presided over by fur trading company managers who, with the cooperation of Russian Orthodox priests, had designated Sugpiaq men as village chiefs (AOM 1902). The system had ceased by 1902, leaving village affairs in the hands of the indigenous village leaders. By 1912 local support was an essential factor in the choice of chief (Partnow 2001).

Christianity had been a strong force in the two communities since the smallpox epidemic of 1838 (cf. Partnow 2001, ARCA 1898, AOM 1898). Everyone attended church and took part in seasonal Christian celebrations and ceremonies. Literacy was relatively high, even though neither village had a school. In Douglas, 20 years earlier, the trader had reported that someone in every household was literate (Stafeev 1892). The Bible and its teachings were well known and incorporated into local culture.

Photograph courtesy of Patricia H. Partnow

The Katmai Story

The story itself has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Partnow 1995). It is a story of rebirth and regeneration, reminiscent of both Genesis and Christ’s resurrection. The story begins with Katmai as a bountiful Eden that was completely destroyed by the volcano. People were buried alive in their sod houses for three days before they could dig out and send the three most able men paddling into Shelikof Strait for help. The story casts the disaster in the role of a corrective event that forced its victims to reconstitute their communities. As often happens in cases of such disasters, the event became both a culprit and creator (Hoffman 2002). Eventually the group chose to resettle far down the coast in a village they named Perryville, after the captain of the ship that transported them there (Figure 4).

As it is told today, the saga is imbedded in two periods: the world of 1912 and the world a generation later when the story was first recorded and transmitted to the outside world. In August 1912, the Revenue Cutter Service captains who had rescued and helped relocate the people issued reports describing their pivotal role in the rescue (USRCS 1912). Other first-hand recollections were recorded by Afognak residents who sheltered the refugees (Harvey 1991). The story from the point of view of the Katmai and Douglas participants was first published in 1956, when Harry Kaiakokonok, who had been 5 years old in 1912, wrote and distributed his recollections (Kaiakokonok 1956). Fifteen years later, he and an older neighbor, George Kosbruk, recorded an interview with NPS rangers (Davis 1961). The story people tell nowadays is based on the testimony of these two men.

The story differs according to the teller’s perspective. Aside from slight differences in detail, the primary contested area lies in the nexus of power. Revenue Cutter personnel believed that theirs was the central role, and that, for instance, the Sugpiat would not even have put up fish for the winter if they had not been told to do so (USRCS 1912). Afognak hosts saw their cousins as quaintly backward and needy. In contrast to both views, the Katmai people cited strong continuous leadership who decided where to settle, how to organize the people in the new village, and how to distribute the building materials and food provided by the government (Kosbruk 1992).

Alaska State Library PCA 222-370, Leslie Melvin Collection

Magnitude of Disruptions

To what extent were the people of Katmai pre-adapted to the disaster they survived? The answer requires a consideration of the magnitude of disruptions of place, time, and people.

Place

This is an example of complete spatial disruption. The people had to abandon their homes, leave most of their belongings, and move away from the territory they had known for uncounted generations. Yet there were mitigating circumstances. The terrain, fish and game, and natural resources in the new village site were similar. The new site offered opportunities for cash income, since the commercial fishing industry had just opened up to Alaska Native workers. Perryville was both close to the fishing center of Chignik and far enough away to avoid disruptions brought by foreign workers.

The area had previously boasted a small community at Mitrofania, founded some 30 years before the settlement of Perryville. These locals helped orient the Katmai refugees to their new home and most married into the community. The fact that the refugees had been a highly mobile group, used to traveling and relocating, and famil-iar with a wide swath of territory long before the eruption, placed the move in the context of customary experience. The disruption was complete but not catastrophic.

Alaska State Library, Leslie Melvin Collection

Time

The ordeal itself lasted several days: three days of darkness, with thunderous noises and a deluge of ash, and several more days awaiting deliverance. Then for a month, the survivors waited in Afognak before moving to the new village site. Luckily, resettlement occurred in time for people to catch late runs of salmon and put up food for the winter. They were able to build houses before winter struck. They explored the terrain and learned where game could be found. And finally, the eruption occurred in a transitional period when the people were already being forced to abandon one way of life and seek another.

The Vulnerability Profile of the Katmai/Douglas Region

These factors add up to a series of positive pre-adaptations and a fairly low vulnerability profile that included the following:

- A local power structure, which was carried over intact to the new settlement and played a critical role in the relocation;

- A history of mobility, which meant people were knowledgeable and comfortable in a wide range of locales;

- A religion that comfortably embraced the event in its existing narrative and value system;

- The recent breakdown of an economic system, so what might have been sudden and new was actually part of a change to which people were already adjusting;

- An insularity from neighbors, which lent itself to a definition of the people of Perryville as a “chosen people” who were destined for change;

- A technologically simple infrastructure that was easily rebuilt;

- A pre-existing relationship with the federal govern-ment, which sped up assistance both in the rescue from the coast and the transportation to Perryville.

Photograph courtesy of Patricia H. Partnow

In summary, Katmai was far less vulnerable to social disruptions than might be assumed, in that its social structure persisted throughout all stages of the disaster and the people saw themselves as responsible for decisions about their future. The community was put in a dependent position only temporarily while at Afognak. Their experiences there, which were characterized by a separation due to social and cultural differences with the hosts, served to solidify the distinct identity of the Katmai and Douglas people and propelled them to seek another place to live.

Even with these mitigating factors, the huge social upheaval caused by the eruption should not be underplayed. The event brought about cataclysmic cultural change. Whereas Katmai was a village rooted in the past, Perryville was conceived from the beginning as a modern, forward-looking town. The leadership engineered and incorporated a number of changes. Within ten years, the federal government opened a school, with the result that English became the dominant European language, supplanting Russian. Since everything had been lost in the eruption, including clothing and belongings, the material culture in Perryville was strikingly different from Katmai. Most people built their new houses of wood rather than sod. People bought clothes, toys, and household goods from catalogues. The village planted foxes on a nearby island to provide regular cash flow. A baseball team, the Perryville Bears, was formed to play Revenue Cutter Service and neighboring teams (Figure 7).

And just before the move, cannery policies changed, allowing Native people to work there, thus solidifying involvement in the cash economy and participation in the modern era.

Katmai lives on, but primarily as a story of a distant, perfect, forever lost garden.

References

Alaska Orthodox Messenger (AOM) (Pravoslavnyi Amerikanskii Vestnik). 1898. Short Church Historical Description of the Kodiak Parish. Draft translation by P.H. Partnow. Vol. 2: 265-6, 508-510.

Alaska Orthodox Messenger (AOM) (Pravoslavnyi Amerikanskii Vestnik). 1902. Report of the Voyage of Vasilii Martysh, taken in 1901. Draft translation by P. H. Partnow. Vol. 6: 431-3.

Alaskan Russian Church Archives (ARCA). 1898. Microfilm, Reel 175. University of Alaska Anchorage Archives (originals in Library of Congress, Manuscript Division).

Blaikie, Piers, Terry Cannon, Ian Davis, and Ben Wisner. 1994. At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters. Routledge. London.

Davis, Nancy Yaw. 1986. A Sociocultural Description of Small Communities in the Kodiak-Shumagin Region. Minerals Management Service Technical Report No. 121. US Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region. Anchorage.

Davis, Wilbur. 1961. Mount Katmai, Alaska Eruption. Audio recording and transcript at the University of Oregon Archives.

Harvey, Lola. 1991. Derevnia’s Daughters: Saga of an Alaskan Village. Sunflower University Press. New York.

Hoffman, Susanna M. 2002. The Monster and the Mother: The Symbolism of Disaster. In Catastrophe and Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster, edited by Susanna M. Hoffman and A. Oliver-Smith, pp. 113-142. School of American Research Press. Santa Fe, NM.

Kaiakokonok, Harry O. 1956. Story. Photocopy of manuscript originally published in Island Breezes. Public Health Service. Sitka, AK.

Kosbruk, Ignatius. 1992. Interview conducted, recorded and transcribed by Patricia Partnow. Perryville, Alaska, March 24.

Oliver-Smith, A., and S. M. Hoffman. 2002. Introduction: Why Anthropologists Should Study Disasters. In Catastrophe and Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster, edited by Susanna M. Hoffman and A. Oliver-Smith, pp. 3-22. School of American Research Press. Santa Fe, NM.

Partnow, Patricia. 1995. Days of Yore: Alutiiq Mythical Time. In When Our Words Return: Writing, Healing, and Remembering Oral Traditions of Alaska and the Yukon, edited by Phyllis Morrow and William Schneider, pp. 139-184. Utah State University Press. Logan, UT.

Partnow, Patricia. 2001. Making History: Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Life on the Alaska Peninsula. University of Alaska Press. Fairbanks, AK.

Porter, Robert Percival. 1893. Report on population and Resources of Alaska at the Eleventh Census. US Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C.

Stafeev, Vladimir. 1892. Unpublished diary translated by Marina Ramsay, edited by Richard A. Pierce.

United States. 1910. Census of Alaska.

United States Revenue Cutter Service (USRCS). 1912. Annual Report. Archives 671, Roll 16. Records and Communications. US Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 11 Issue 1: Volcanoes of Katmai and the Alaska Peninsula.

Last updated: August 17, 2017