Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 19, Issue 1 - Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Underwater World.

Article

SONAR Project Provides Coho Salmon Baseline for Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

NPS/CRAIG MURDOCH

Pacific Salmon are a quintessential symbol of wildness and vitality. They are also a critical component of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve’s (NP&Pres) ecosystem. Not only are they an important food source for many creatures, including bears (Ursus arctos and U. americanus), wolves (Canis lupus), harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and people, they also fertilize streams and nearby forests with their decomposing bodies (Gende et al. 2007). Each summer Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve’s Bartlett River is home to runs of sockeye (Oncorhychus nerka), pink (Oncorhychus, gorbuscha), chum (Oncorhychus keta), and coho (Oncorhychus kisutch) salmon. Glacier Bay National Park managers are working to ensure that healthy salmon runs continue within one of the park’s most heavily fished rivers.

Glacier Bay NP&Pres managers prioritized a study estimating coho salmon escapement (passage upstream to spawning grounds) and harvest in anticipation of increased fishers due to improved regional ferry service. Fisheries staff responded by deploying high-resolution sonar (Dual-frequency IDentification SONar or DIDSON) to image and count coho salmon migrating up the Bartlett River during 2012-2014. Therefore, the park prioritized obtaining coho salmon escapement (passage upstream to spawning grounds) and harvest estimates. Though Glacier Bay NP&Pres is a relatively remote wilderness park, the Bartlett River draws anglers from far and wide. Our objective was to determine baseline abundance and harvest information to ensure current and future levels of coho salmon harvest are sustainable.

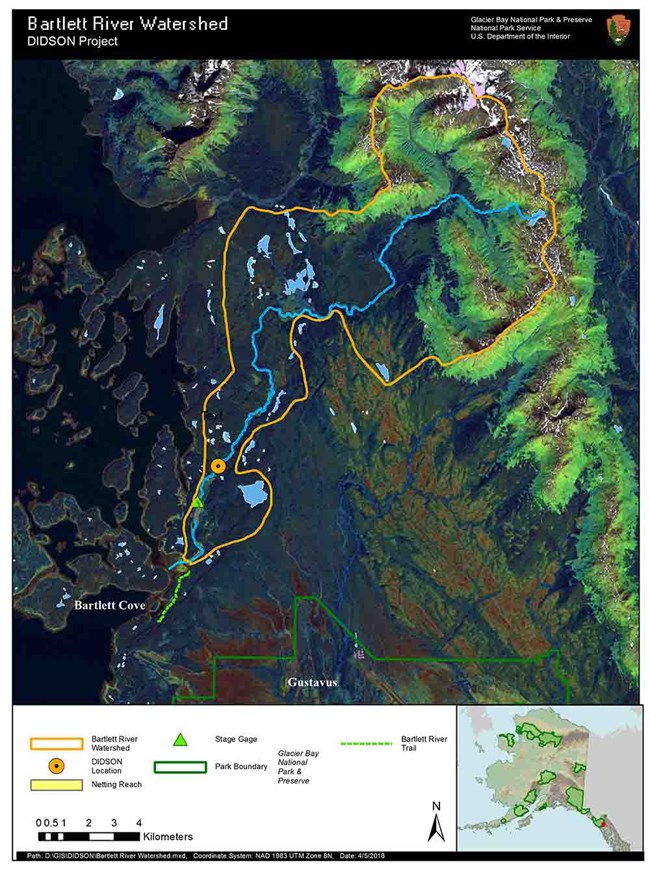

The Bartlett River is a relatively small wilderness stream that follows the lateral moraine left by the Glacier Bay ice sheet several hundred years ago (Figure 1). The river has experienced much change in its approximate 250-year history due to the retreat of the Glacier Bay ice sheet, isostatic rebound, and successional processes. Today, typical summer stream flows are between 100 and 300 cubic feet per second (2.8-8.5 m3/sec). Several small mid-basin lakes buffer flows and serve as sockeye salmon spawning and rearing habitat. The headwaters derive from Excursion Ridge just 22 river miles (35.4 km) from its mouth near Bartlett Cove. The ridge bears karst geologic features, which have been associated with a positive influence on fish productivity and invertebrate diversity and abundance (ADFG 2014).

Early commercial ventures in salmon canning and salting near the mouth of the Bartlett River suggest it was once teeming with salmon. The Bartlett Cove saltery packed 120,000 pounds of sockeye fillets during the summer of 1899, which would equal approximately 30,000, six-pound sockeye. The following year approximately 24,000 pounds or 3,500 coho salmon were salted; most are believed harvested from the Bartlett River. Cannery operator August Buschmann estimated the Bartlett River held 75,000-100,000 “beautiful large red salmon” in 1901 (Buschmann 1960). That same year, naval commander Jefferson Moser (Moser 1898) during his investigation of Alaska salmon fisheries estimated that the Bartlett River could produce 50,000 sockeye salmon in a good year. Though commercial salmon fishing in Bartlett Cove continued during the early 1900s, the saltery went bankrupt in 1903. By 1924, Congress passed the White Act to limit commercial fishing. Glacier Bay was one of 15 areas considered depleted of salmon in Southeast Alaska, and it was completely closed to all forms of commercial salmon fishing (Mackovjak 2010).

Today, salmon fisheries in Alaska are far better managed. Though the Alaska Department of Fish and Game estimates Southeast Alaska monitored coho stocks experience substantial, but moderate exploitation rates ranging between 38-64% (average 52%) of annual returns from 2006 through 2010, stocks have remained productive and healthy (ADFG 2011). Commercial harvest rates of Bartlett River coho are likely average or less than average due to the river’s distance from other intercept fisheries, such as the Lynn Canal gill net fisheries. Beyond commercial salmon trolling, mostly outside Glacier Bay, it’s likely that only recreational anglers harvest salmon from the Bartlett River.

Recreational fishing is a treasured American pastime and many parks were explicitly set aside to encourage recreation, including sport fishing. Shortly after Congress created the National Park Service (NPS) in 1918, Department of the Interior Secretary Lane wrote to the first director, Stephen Mather, announcing “Mountain climbing, horseback riding, walking, swimming, motoring, boating and fishing will ever be the favored sports”...within National Parks (Lane 1918:50). This is still true today, though an increased emphasis on preserving native fish has evolved.

NPS Policy is to “…maintain all the components and processes of naturally evolving park ecosystems, including the natural abundance, diversity, and genetic and ecological integrity of the plant and animal species native to those ecosystems” (NPS 2006: 36). Further, policies stipulate that the service will allow harvesting of plants and animals only when monitoring is conducted and the NPS has determined that the harvest will not unacceptably impact park resources and natural processes (NPS 2006). Goal 18 of the Alaska Natural Resource Program Implementation Plan (Adema 2014:23), states that “... managers have adequate information to manage harvested resources to a natural and healthy standard.” Yet in the past one hundred years little new information on salmon abundance in the Bartlett River has been attained and few estimates of harvest exist.

Fisheries scientists use a variety of techniques for estimating the size of salmon runs, but recent technological advancements in sonar and power generation provided a relatively low-impact wilderness-friendly approach. DIDSON uses 96 high-frequency sound pulses (1.1 or 1.8 MHz) to create near video-quality images of migrating fish. Our DIDSON system autonomously and continuously recorded 8 frames a second or roughly a gigabyte of data an hour, day and night for the duration of each survey season. DIDSON requires only 45 watts of power, making it feasible to use a quiet, clean methanol fuel cell (45 dB, water and CO2 emissions) rather than a gasoline generator (Figure 2).

The largest challenge we faced using DIDSON was its inability to differentiate between fish species. Though DIDSON can be used to accurately and precisely measure fish length, length alone is an inadequate predictor of species when multiple species with overlapping length distributions are simultaneously migrating (Burwen et al. 2010, ADFG 2007; Figure 3). Our pilot study in 2011 determined that pink and chum salmon and, to a lesser extent, Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma) exhibited overlapping length distributions and run timing with the coho migration. Though DIDSON’s inability to differentiate between species may make it a suboptimal tool, there are methods of estimating mixed stock migrations of salmon.

One commonly used method of estimating the proportion of species is by sampling migrating fish with a tangle net. We used a 40-50 foot- (12-15 m) long tangle net with appropriately sized mesh to entangle the head, jaws, and teeth of migrating fish. The objective of tangle net sampling of upstream migrating fish was to obtain an unbiased, representative sample of upstream migrating species composition in order to apportion the contribution of coho salmon relative to overall DIDSON imaged salmonids.

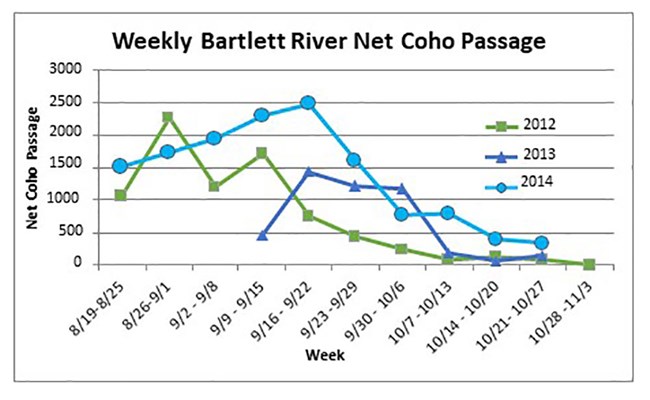

The use of DIDSON in conjunction with tangle netting and creel surveys successfully revealed a productive coho stream, with little angler harvest. We estimate minimal escapement estimates of between 4,600-13,900 coho for the years 2012-2014 respectively (Table 1, Figure 4). Our minimum estimates of coho escapement are consistent with ADFG’s determination that Southeast Alaska streams with lake systems on average produce escapements of 1,000-8,000 coho annually (ADFG 1989).

| Year | 2012a | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Net Coho Estimates | 7,207 | 4,651b | 13,902 |

| 95% CI Annual Net Coho Passage | 5,362-10,577 | 3,389-5,914 | 11,784-16,019 |

| Period of Record | 8/19-10/27 | 9/12-10/26 | 8/17-10/26 |

aInadequate net sampling prevented species apportionment in 2012. This estimate includes all salmonids greater than 40 cm.

bOur 2013 estimate of coho escapement is truncated due to large numbers of pink salmon spawning near the sonar site during the early coho run.

Recreational fishing effort and harvest were highly variable. We estimate between 179 and 442 anglers harvested 158, 2,019, and 300 coho over the three years (Table 2). Our estimates of effort and harvest are relatively consistent with existing ADFG Statewide Harvest Survey estimates, which also suggest relatively low and variable harvest and effort compared to other streams of similar size elsewhere in Southeast Alaska. Annual recreational harvest estimates ranged greatly from 2% to 43% of our escapement estimates. Though 43% is high for 2013, our estimate of coho escapement was delayed due to high numbers of pink salmon spawning near in the vicinity of the sonar. Had the escapement estimate started in the 3rd week of August as in 2012 and 2014 the recreational harvest would be a much smaller percent of total escapement.

| Year | 2012* | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Anglers | 179, 1SE 33 | 442, 1SE 57 | 230, 1SE 40 |

| Coho Harvest | 158, 1SE 128 | 2,019, 1SE 587 | 300, 1SE 144 |

| % of Escapement | 2% | 43%* | 2% |

There are several factors that likely contribute to the large year-to-year variation in recreational harvest and effort. It is likely a product of environmental conditions, angler success dissemination, and salmon run size. According to the Western Regional Climate Center (WRCC 2020) average precipitation in September for Bartlett Cove near the Bartlett River is 10.02 inches (25.5 cm). While 2012 had average precipitation, 2013 was nearly 2 inches (5 cm) less than average. Wet fall conditions are often favorable for salmon migration while often making fishing more challenging for anglers to target. Dry, low-water conditions result in salmon holding in the lower river where anglers can target them. Further, wet conditions degrade trail conditions and make the 2-mile (3.2 km) hike more challenging. When catch rates are high, word travels fast, leading to increased angler effort. Poor angler success likely has the alternate effect. 2013’s relatively high coho harvest is also a consequence of high returns. ADFG reported record salmon returns across Southeast Alaska in 2013 (ADFG 2013).

Despite concerns about increased recreational harvest from new Alaska Marine Highway Ferry service to Gustavus, there is no indication that recreational fishing harvest is jeopardizing a natural and healthy coho salmon population in the Bartlett River. Recreational fishing effort and harvest are currently low and variable, and though the largest component of harvest (i.e., commercial) is unknown, our escapement estimates indicate the Bartlett River exceeded biological escapement goals set by ADFG for other similar drainages in Southeast Alaska (Situk River 3,300-9,800, Ford Arm Creek 1,300-2,900; ADFG 2014). Though, there is currently no threat of impairment, this work highlights the importance of baseline information as a reference point to assess future change. Further, it is imperative for managers to have clear management objectives and biological thresholds by which to manage. Given the looming dark clouds on the horizon in the form of climate change, ocean acidification, and increased human demands, baseline information is the first step in avoiding diminished, less resilient ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the many hours our dedicated staff persevered through the often soggy, cold and dark Southeast Alaska fall months. Thanks for all your hard work: Leslie Skora, Mike Lehman, John Rodstom, Kathleen Doran, Katie Rayfield, Georgia Arnold, and Jennifer Hamblen. We would also like to extend gratitude to Alaska Department of Fish and Game employees Debbie Burwen, Suzanne Maxwell, Carol Coyle, Roger Harding, and David Love for their technical assistance and loan of equipment.

References

Adema, G. 2014.

The Alaska Natural Resource Program implementation plan 2013-2018. Natural Resource Report NPS/AKRO/NRR—2014/764. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). 1989.

Information on coho salmon stocks and fisheries of southeast Alaska. Regional Information Report. 1589-03.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). 2007.

Evaluation of a dual-frequency imaging sonar for detecting and estimating the size of migrating salmon. Fishery Data Series No. 07-44.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). 2011.

Coho salmon stock status and escapement goals in southeast Alaska. Special Publication No 11-23.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). 2013.

Press Release: October 10, 2013. Juneau, Alaska. Available at: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=pressreleases.pr10102013 (accessed April 5, 2019)

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). 2014.

Review of salmon escapement goals in Bryant, M. D. and D. N. Swanston. 1998. Coho salmon populations in the karst landscape of north Prince of Wales Island, southeast Alaska. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 127: 425-433.

Buschmann, A. 1960.

Letter to Mr. F. H. Jacot, Superviosry Park Ranger, Glacier Bay National Monument, Buschmann, Seattle, WA dated June 28, 1960.

Burwen, D. L., S. J. Fleischman, J. D. Miller. 2010.

Accuracy and precision of salmon estimates taken from DIDSON sonar Images. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 139: 1306-1314.

Gende, S. M., A. E. Miller, E. Hood. 2007.

The effects of salmon carcasses on soil nitrogen pools in a riparian forest in southeastern Alaska. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37(7): 1194-1202.

Lane F. 1918.

Secretary Lane’s letter on national park management. In: Lary M. Dilsaver, Editor. America’s National Park System: The Critical Documents. 1994. Lanham. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 48-52.

Mackovjak, J. 2010.

Navigating troubled waters: Part 1 A history of commercial fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska. U.S. Dept of Interior, National Park Service, Glacier Bay National Park, Gustavus, AK.

National Park Service (NPS). 2006.

Management Policies 2006. United States Department of the Interior. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado.

Vander Haegen, G. E., C. E. Ashbrook, K. W. Yi, and J. F. Dixon. 2004.

Survival of spring Chinook salmon captured and released in a selective commercial fishery using gill nets and tangle nets. Fisheries Bulletin 68:123-133.

Western Regional Climate Center (WRCC). 2020.

Glacier Bay, Alaska climate summary. Available at: https://wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?akglac (accessed March 11, 2020)

Last updated: May 29, 2020